Contemporary Problems, Interventions and Results

See preceding section:

5. Current Audio Problems

6. Interactions with Composers

6.1 Mastering and Professional Production

The professional production milieu reacted early on to exportability problems, in fact as soon as they understood the important risk factor these problems could bring to production costs. For example, an extraoardinary variety of side-effects arose because of the disparities of the monitoring systems between studios: painful self-questioning, conflicts between teams, parallel mixes, not to mention product returns, broken contracts, legal processes, etc. Some of the situations reported were as extravagant as they were costly. For example: having waited for months on end for an album to be mixed, the record company sends repossession agents to seize the master tapes; or the case where the entire production team travels from one continent to another… to “remix the snare”, etc.

As they matured to fruition, a variety of solutions associated with mastering (addressed at the beginning of this article and elsewhere [3]) were simply imposed by the commercial milieu, an act which was possible thanks to its extremely hierarchical corporate structure. The changes were implemented without any real debate, but the argument was and still is strongly substantiated by a spectacular improvement in the quality of the productions.

Directors and producers quickly accepted the necessity of the mastering studio, and following initial experiences — often traumatic — with the honesty of the new monitoring references, they began to fully cooperate with mastering engineers, (4) and to even consider that their own work ended with the mixing, the subsequent steps being attended to by persons who had very specific competences. (5) This division of labour resulted in the specialisation of tasks, allowing the milieu to objectify problems and to concentrate on the solutions.

6.2 Mastering and Electroacoustic Production

Working methods in electroacoustics do not allow for this objectification: the composer is often responsible for financing their production, and therefore the power remains in their hands, on a number of levels. Once they have composed, recorded and mixed their disc, they find themselves having to approve of someone else’s mastering. This is a situation which completely lacks detachment, is too intimately linked to a variety of sensitive points to benefit the product, and where each treatment, every equalization applied during mastering, can be perceived by some as questioning their general competence.

For others there is a clearly defined kind of insecurity concerning the sonic impact of their pieces. Here the higher frequency content is particularly critical: according to a fairly persistent prejudice — a concern that their work will “lack punch” — many composers prefer to have a little “too much”, which however causes irritation on the part of the audience. The kind of impact sought here is an abusive transposition of the “wall of sound” approach, which is commonly used in concerts and is more and more considered to compromise the safety of the audience. Experience shows that most sound systems do not have a sufficient power reserve to effectively reproduce this effect without introducing significant amounts of distorsion, which can quickly deter even the most dedicated enthusiasts. Mastering must make use of more subtle and varied approaches to develop and maintain the interest of the audience, at the same time ensuring a comfortable listening level for them.

In all of these cases — fortunately not the majority — mastering becomes a theatre featuring various emotionally-charged scenes: an overview of its dramaturgical structure can help us understand the situation.

6.3 Reactions

Upon hearing mastered pieces for the first time, the composer is initially enthusiastic, because of a more stable aural image and better spectral balance; one would expect that this reaction foreshadows that of the listener. While many composers are content to assume the same, others are tempted to perform a meticulous A/B comparison with the original mix. Especially when the comparison is done in the studio where the work was mixed, (6) they start to notice passages which were “better before”, thus contradicting the initial holistic impression.

The mastering engineer then receives a list of precise corrections to implement, placing him in a particularly delicate position. He must respond to the demands of the composer — his client — but must also inform him that the corrections cause not only a return in the direction of the original, but also, for the most part, an actual regression in regards to the advantages obtained in the mastering.

Next, a rather strange round of negotiations ensues where each decibel of equalization — or more precisely, its removal — becomes the object of a game of manœuvering which eventually produces a compromise version. This version can be just about anything between a hybrid of the mastered version and the original mix to a virtual replica of the latter.

In many cases, however, as described in the Mixtering article, the composer ends up having doubts about the whole process and takes the work elsewhere to listen to, where he discovers — to his surprise — that the mastered version is more solid…

There is no other solution to this problem than that which was implemented in the pop milieu: professionalization, specialization of tasks, dissemination of information and knowledge.

7. Mastering Session of Yellow Flowers

A recurrent request has been to detail an entire mastering session step by step, supported by screen captures and audio examples. It may seem paradoxical to provide such a demonstration while insisting here and elsewhere that it is in fact preferable for the composer to avoid intervention in the equalization levels and dynamic control in order to preserve audio quality and leave all the latitude necessary for the mastering stage. That said, by showing exactly what happens in the course of a mastering session, we:

- expose and demystify a process considered by some to be mysterious and worthy of apprehension;

- inform the community of composers about an essential stage in the production process;

- clearly indicate to the composers which processes should not be applied at the stages of multitracking and mixing…

It bears repeating that none of the decisions described below can be taken safely unless one has access to:

- a monitoring (acoustic control + speakers) calibrated according to the standards used in professional mastering;

- tools for equalization and dynamic control of very high standards;

- extensive experience in mastering.

7.1 Initial Analysis

The composer Freida Abtan, whose subtle movements disc was being mastered, has agreed to have the entire process of a mastering session to be transcribed and presented. Because of its spectral and dynamic variety, the piece Yellow Flowers was chosen. (7) This session was delivered in stems, (8) which normally guarantees a certain quality. It should be noted that this piece was composed as the audio component of a video, and so much of the production was done using specialized video production software which has a sampling frequncy of 48 kHz. As the source audio materials were at 44.1 kHz, a number of sampling frequency conversions had been done using available algorithms, whose semi-professional quality always leaves “artifacts”… a polite way of saying they are responsible for an impoverished sound and an abundance of clicks. The most apparent defaults were corrected, but a certain number always remain and are more or less audible depending on the precision of the system they are played on.

The presentation of all of the processes described below are cumulative: an audio example showing the effects of the first equalizer band will contain only the effects of this band, but when followed by a description of the effects of the second and third bands of the same equalizer, the accompanying audio example will in fact contain the effects of all three bands. Note that the composer was present during the entire session and approved both the subjective interpretations of her compositional intentions and each of the corrective steps.

It can happen that a session delivered in stems is of such a quality that it is then possible to do the mastering directly on the master, only working on the stems when conflicts arise from the global processing. For example, raising the general level of the region 2–2.5 kHz by 3 dB would seem to improve the ensemble, with the exception that stem“X” then becomes too aggressive. Without access to the stems, the only possibility is to accept the compromise of an overall 1.5 dB increase. However, with the stems it would be possible to apply equalization or change the level of stem “X” in a manner that allows for the overall increase of 3 dB, or alternatively to raise all stems but “X”.

In other cases, the sound is more problematic right from the start, and a variety of problems can be detected on each individual stem. Then it is necessary to begin by analysing and correcting the individual stems before passing on to the stage where general processing is applied. This working mnethod is the one that will be adopted for this session.

Listen to the reference track (see Fig. 1, track 14 in red), which is the sum of all stems before mastering. If the separation in stems was done meticulously, this sum should in principle be identical at all levels to the initial mix done by the composer:

Listening to this example, the following deficiencies can be noted:

- the sonic elements seem small, and the ensemble lacks breadth;

- we perceive a certain number of gaping holes in the frequency continuum;

- the spatial representation is confined, fragmented and incoherent;

- there is a predominance of sonorous irritations and obstinate resonances;

- the sound is somewhat granular and hesitant;

- a notable lack of impact characterizes the transients and the crescendi.

7.2 Processing of the Stems

Stem 8: “Slowed Bells”

We will begin with this stem, for the simple reason that it is present throughout the piece, and if not the central element, is certainly the unifying one. After verifying the consistency of the spectral and dynamic content through the stem, a representative excerpt is selected (02:00–02:30) to serve as an audio example:

- the sound is thin and does not give any sense of definite space;

- however, concerning the intention, the composer confirms that she initially wanted to produce a deep and full sound, which develops in a very vast space.

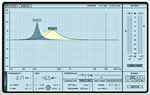

A dynamic equalizer is applied. Figures 2–5 below detail the action of the EQ, band by band.

Band 1 is set to “static” mode, and a wide strip around the centre frequency of 117 HZ is raised by 12 dB (Fig. 2). This may seem a considerable addition, but note that it causes no adverse effects related to swelling or resonance. Here is the result:

The second band functions in dynamic mode, as shown in the following screen capture (Fig. 3).

Note that its effect is inverted, meaning that the increase of 6.5 dB at 317 Hz affects only that which is below the threshold of -44.4 dB. This gives the passage more body but leaves the attacks unaffected; at this frequency it would have caused unpleasant distorsion. The result:

Band 3 is also completely dynamic, but only functions above the threshold (Fig. 4).

Here we wish to bring out the attack but to avoid raising the mids during the decay portion. This explains why the release time has been extended to 569 ms. Setting bands 2 and 3 to work in opposite manners adds interest and movement to the sound:

Two observations remain to be made concerning high frequencies:

- the minor but effective presence of noise and artifacts in this region;

- the nature of transients, which is in strong opposition with the subjective context produced by the sound : the effects applied to this stem create an image of faraway bells, of medium size, thick and heavy, that are struck mezzo forte with felt-headed mallets. However, the presence of transients in the extreme highs contradicts both the notion of distance and the actual nature of the attack of the mallet, which seems to be made of a much harder material and struck forte.

Band 4 was used successfully to offset these problems:

In order to make the sensation of space more pleasant, reverb is added to this stem in the usual manner, via the auxiliary sends (Fig. 6).

The kind of reverb chosen for this excerpt isn’t the kind of brilliant reverb that adds a veil of higher frequencies, but rather one which gives the impression of an underlying slow, majestic movement to the passage. Note the use of the “crossfeed” function, which inverts the first reflections of the left and right channels, thus reinforcing the illusion of movement within the artificial space we have created:

Stem 1 : “Accents”

This stem (Fig. 1, track 1), is constituted of very short events. The longest of these, taken from around 00:25, will serve as an example:

What are the problems?

- lack of vibrancy and definition;

- although the extreme lows seem to be an integral part of the sonic movement, they are hardly noticeable in the original.

Since the events found in this stem are very short and the same kinds of frequential adjustments are needed throughout their attack and release portions, we decide to apply a passive equalizer to the first two bands as follows:

The only adverse effect resulting from the massive increase of 18 dB to the frequency range below 67 Hz (band 1) is a slight — and predictable — swelling, which is however corrected by lowering the basses by 4.5 dB around 94 Hz (band 2). Here is the result:

Although this process has restituted the foundations of the sound, the phrase remains passive and seems to be lacking vigour. Some of its action is still missing, due to a gap in the low-mids that needs to be raised:

The internal dynamic movement is now perceptible: the boost at 369 Hz gives an active impulse to the peak of each wave, the effect of which is clearly audible in this clip:

Bands 4 and 5 take on the high frequencies:

Band 4 helps “accelerate” the perceptible movement by correcting the lack of definition in the hi-mids with a boost of 3.5 dB at 1.27 kHz. The increase of the extreme highs (band 5) may seem excessive by itself, but was found to be necessary when all stems were present.

Stem 2: “Backwards Strings”

Before processing, a number of problems are encountered in this extract (02:20 to 02:45 ; see Fig. 1, track 2) from stem 2:

- swelling in the bass;

- persistent resonance in the mids;

- the waves lack dynamic definition, diminishing the dramatic effect;

- the sound is mono, which immobilizes it spatially, in complete contradiction with the dynamic suggested by rolling waves.

The first operation on the lows is illustrated here:

Once the overly dominant 87 Hz fundamental (band 2) is corrected, the extreme basses (7 dB below 54 Hz, band 1) can be raised, which brings out the “reverse” effect of the sound. The movement is both more dynamic and more explicit:

Figure 11 shows, among other things, the clean-up of the resonant frequency (642 Hz, band 4), the presence of which caused two problems:

- it gave a nasal quality to the sound;

- it caused incoherence in the spatialization: by giving the impression of strong presence, it contradicted the subjective impression of a mass which broadens as it fades into the distance. Once the frequency at fault has been cut back, the ambivalence of the distance effect and in the movement of the sonic object is no longer evident.

Sonically, this opens up another possibility that we can take advantage of by treating the ripping sound which intervenes during each of the waves. Obviously we do not wish to give the sound more presence — which would contradict its spatialization even more — but simply to give it more body and reality, through a 6 dB increase at 161 Hz, seen in band 3. The dynamic effect of the rolling wave is once again clear:

The stem is of course still mono, but we offset that by adding the same reverb as was done on stem 8 (see Fig. 6). Again, the effect may seem exaggerated when heard by itself:

but heard in context, this dosage brings it just above the threshold of perceptibility. Figure 12 shows that for the final sustained portion of the extract, the send to the reverb has been cut in order to better reveal the slow volume modulations at the end of the phrase. A slight increase in volume compensates for the loss of subjective volume caused by cutting the reverb.

Stems 3, 4, and 5: “Bell Group”

These three bell sounds (see Fig. 1, tracks 4–6) are similar, so it is decided to process them together via a sub-group. The pre-mastered version is taken from 00:51–01:09.

- the sound is too “ringing” in the hi-mids, but it lacks presence in the extreme highs — where we should expect it — and therefore comes across as inadequate;

- the sound is small, which is not descriptive of the physical dimensions of the source, but rather suggests an amateur recording technique.

Figure 13 shows the settings of bands 1 and 3. The manipulation noises are eliminated by the hi-pass filter at 217 Hz, while the body of the instrument’s sound is reconstituted by significantly boosting the lowest bass frequency present, 424 Hz. The event sheds its dull side in exchange for a more bouncy character that is more in tune with its apparent nature:

All that remains is to process the upper part of the spectrum:

Band 4 eliminates a resonance which dominates in an unpleasant manner at 2 kHz. The sound acquires transparency and lightness, and it is now possible to appreciate both the body and attacks. Band 4 raises the extreme highs, giving the excerpt a hi-fidelity character that it was lacking. The smallness seems now to be subjectively attributed to the source object, and not to the recording, which was previously the case:

Once returned to the mix, this group still seems a little timid, in particular the central portion of the excerpt, which comes from a separate stem. We will raise the high transients of this stem — but not those of the entire subgroup — using a multi-band transient processor (Fig. 15).

Only the upper two bands are affected: band 4 starting at 6 kHz, and with less intensity, band 3 between 3.3 and 6 kHz. Contrary to an expander, this tool identifies transients by analysing the attack time. This offers a notable improvement in the audibility of the transients, but limited to only the extreme highs, which ensures a much more delicate result. When we previously tried to apply the same process in full band mode, it only amplified a displeasing attack in the hi-mids.

Stem 6: “Drone”

Starting from the passage between 01:12 and 01:43 (see Fig. 1, piste 8) we note the following problems:

- the lack of bass frequencies is flagrant, and there is no way to raise this spectral region properly or efficiently using an equalizer;

- the mid frequencies dominate and become unpleasant in the central plateau;

- the intention is to produce a deep, menacing effect, but the effect is not convincing.

As it seems to be impossible to simply raise the sub-basses of the original stem via equalization, we make a copy of the stem and transpose it down an octave, but without changing the length. The gain of the new track will be at unity, but we will reduce the volume of the upper octave by 4.5 dB during the plateau (Fig. 16).

This allows us to retain the dynamic of the plateau while controling the mid content. The result presents no signs of booming and can therefore be used as is:

Stem 7: “Screaming Bird”

The two sounds found in this stem (see Fig. 1, track 10) are taken from the same source but have been processed differently. They will probably both require similar and different processing.

A similar light crackling can be heard in the extreme highs of both excerpts. As for the second excerpt (Audio 22b), two additional problems appear: a persistent resonance in the very high-mids, and in the lows, the presence of a noise that could be associated with the bowing or rubbing of a string recorded with a close-miking technique. These two characteristics contradict the sensation of distance that other aspects of the sound seem to suggest.

A noise reducer is used to control the crackling (Fig. 17). With the crackling gone, the sound is more round, and the first excerpt is already usable:

But the second excerpt is still unpleasant, so we use a passive EQ on it (Fig. 18). A severe high-pass filter amputates everything below 1.86 kHz, and a further reduction of 15 dB at 4.1 kHz in band 3 tackles the persistent resonance in the highs. The proximity effect is eliminated and with it any confusion as to the distant ethereal quality of this excerpt. Band 5 is a low-pass filter set at 11.5 kHz. It is interesting to note that despite cutting them by 10 dB we have the impression that the extreme highs have been released and can be perceived more clearly:

Stem 9: “Space”

Other versions of this event are found elsewhere in the stem (see Fig. 1, track 12), each having the same problem, one which is typical of an unfortunately large proportion of electroacoustic productions received for mastering:

- the sound has a grainy character, is piercing and sounds too loud in the context;

- the hi-mids dominate in an aggressive manner;

- the bass frequencies don’t have any presence, and they appear intermittently, almost seeming arbitrary;

- the use of space is vague and imprecise;

- since most of the sound is concentrated in a frequency region where it is already aggressive, every corrective step will be a difficult compromise.

A dynamic equalizer is selected, whose action is explained as follows (Fig. 19). Band 1 is completely dynamic and effects a 15 dB boost at 46 kHz. The threshold is set to affect all the sound, with the exception of the strongest peaks. Band 2, centred around 400 Hz, has both a 6 dB boost in static mode and an extra 6 dB above the threshold. The presence of a fundamental is reinforced, helping it function as a structuring element. Now the sound has a vocal and dynamic quality, whereas before it was only essentially comprised of noise elements: indefinite rumblings in the lows and irritation in the hi-mids.

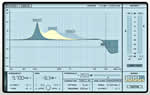

The two other bands complete the work (Fig. 20).

Band 3, entirely static, boldly eliminates (-13.5 dB) one of the principal sources of the irritation in this stem, situated at about 2.1 kHz. Band 4 plays a similar role at 12.5 kHz. In order to preserve a certain presence in the higher frequencies during the softer passages, it is set to only 2/3 dynamic.

It should be noted that even after such severe equalization, the stem is still quite dominant in relation to other elements in the mix. Therefore, its volume was lowered by 4.5 dB. The situation is favourable to such treatments, which would not have been the case if the event appeared alone. Here is the result:

Stem 10: “Watery Sound”

- at the beginning and end of each wave, very pleasing low basses can be heard, but they are too timid;

- there are also some irritating resonances in the mid-range;

- incorrect equalization has introduced irregularities and imprecision to the “natural” envelope of the sound.

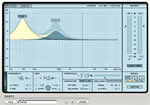

First, the envelope need to be extended to its extremities, in order to give more body to the sub-bass frequencies (Fig. 21). This is effectively accomplished by a radical boost of 18 dB at 44 Hz (band 2), however tempered from below by band 1, a high-pass filter under 26 Hz:

Bands 3 and 4 deal with the higher frequencies (Fig. 22). The dynamic envelope has been rounded off by the boost at 345 Hz and the cut at 2.2 kHz. The gestural form suggested by the sound is now presented with much more precision, and the movement even seems, in a sense, accelerated:

There is an audible distortion, accompanied by clicks, that remains to be resolved (Fig. 23).

7.3 Processing of the “master”

With the last stem corrected, it is time to assess the effects of our work by listening to the sum of all the treated stems:

This excerpt, taken from 00:58 to 01:46, proves to be quite satisfactory, however its subjective volume is insufficient, not just in relation to current electroacoustic trends, but also in relation to other pieces which have already been mastered for the same album, Yellow Flowers.

It is clear that considerable gain will need to be applied, so the intermediary step of a multiband compressor is applied, otherwise there is a risk of causing audible pumping (Fig. 24). Despite the fact that the compression parameters are identical for each band, and that the threshold is high, a certain finesse is now lacking, a result that is typical when compressing the master:

We can recover some of this finesse using an expander. Despite appearances, this will not attenuate the effects of the compressor because its threshold is carefully set to a position below that of the compressor (Fig. 25). Dynamic control is thus applied to the passage as follows:

- the compressor attenuates above -12 dB;

- between -12 and -15 dB the dynamic isn’t affected;

- the expander attenuates below -15 dB.

The difference bvetween the ratios of compression (2:1) and expansion (1:1.03) may seem considerable, but this kind of difference is typical and in the end produces equivalent attenuation levels:

The global volume has now been raised. To account for this change, we slightly rebalance the stems, and add a “Brick Wall Limiter” (Fig. 26). Its task is to bring the piece to a global level that is comparable to the rest of the disc, at the same time giving it an absolute ceiling of -0.3 dB. Here it should be noted that the two channels are linked for this operation, which is applied fullband, although they weren’t linked during compression and expansion, which were less detectable because they were done in multiband mode. The final step is to dither to 16 bits. The final result:

We can hear the complete mastered piece here:

Don’t forget the essential comparison with the starting point!

Notes

- See Dominique Bassal, “A Guide to Producing Stems,” eContact! 6.3 — Questions en électroacoustique / Issues in Electroacoustics (2003). In French and English.

- © Martin Leclerc and Laurie Radford for the original excerpts, and © empreintes DIGITALes for the excerpts from the mastered versions.

- See Dominique Bassal, “The Practice of Mastering in Electroacoustics,” eContact! 6.3 — Questions en électroacoustique / Issues in Electroacoustics (2003), pp. 11–14. In French and English.

- ibid. p. 14.

- ibid. p. 39.

- ibid. p. 50.

- © Freida Abtan for the original and mastered excerpts.

- Bassal, “A Guide to Producing Stems.”

Social top