Dead Lion, or, The Musical Oscilloscope

A Diegetic approach to synthesis and feedback

Since 2012, I’ve been exploring the musical potential of a light-based feedback system using lab equipment and solar batteries. After introducing some early forays into light-listening techniques, I will explain my creation of a light-based synthesizer system using oscilloscopes, photodiodes and a mixer. In addition to detailing the basic performance techniques of this assemblage, I will also define the arcana latent in this system, namely easy manipulation of the undertone series, and a crude sort of pitch tracking that works well for incorporating other audio signals, such as voice or rhythmic accompaniment. Finally, I will conclude with a discussion that links this practice to seminal pieces and approaches in the history of experimental music, and demonstrate my reinterpretation of repertory work using this system.

Early Techniques: Listening to Lights

A photodiode creates a voltage in proportion to the light it receives. Since 2009, I have been using photodiodes to sonify light waves by connecting photodiodes to microphone preamps and pointing the assemblage at interesting light sources. Because of the persistence of vision effect, we see lights blinking faster than 26 repetitions per second as “constant” light sources. This is right around the rate that vibrations seem to become pitch rather than rhythmic content. My technique is to solder a photodiode onto an XLR cable (Fig. 1) to create a “balanced” light microphone and to listen in on the harmonies hidden away in the screens of Times Square. 1[1. This work had been inspired by the circuits and techniques of Bob Bielecki, Eric Archer and Stephen Vitiello.] Initially, I had only used this technique for making field recordings of light pollution. When I first moved to NYC, it was how I made peace with my surroundings — I walked around with the photodiode and conducted my own “symphonies of light” (Video 1). But in these early explorations, I had never utilized the photodiode for instrumental work. It was not until much later that I would create my own system of musical lights.

The Musical Oscilloscope

One day in 2012, I was playing around with photodiodes in my workshop. I had only just recently purchased an oscilloscope, and thus had just begun to think about how a photodiode “sees light” rather than merely listens to light as a found object. After connecting a photodiode to my oscilloscope and pointing it at the sun, I noticed a corresponding increase in DC voltage shown on the scope screen. Wondering about the possibility of feedback, I turned the photodiode around to point at the oscilloscope beam itself. The scope showed a similar vertical spike around the sensor, swinging in a neat “U” shape. I scanned the “seconds per division” setting, hoping to “zero in” on the waveform at its frequency, as I had learned to do. But the waveform remained mostly constant, with some subtle changes that I presumed were artifacts, until I hit the lowest range. I realized that this waveform was not the typical waveform I associated with audio inputs on the oscilloscope; the photodiode was causing a DC offset 2[2. DC offset is the displacement of an audio signal from zero point, or the x-axis. Though it may cause unwanted effects in audio by reducing headroom, an offset cannot be heard with the naked ear. Measurement tools such as oscilloscopes can reveal the inaudible characteristics of waveforms.], represented by the skyward shift in the light beam, which was independent of the frequency setting of the scope.

As the green dot crept across the screen, it dawned upon me that the green CRT beam of my oscilloscope is a very stable sawtooth waveform, and that the photodiode was “listening” to this frequency. The oscilloscope itself could become a synthesizer, instead of its more common usage, to visualize some other waveforms. When one of the photodiode pickups was pointed at the screen, a brilliant sawtooth timbre was produced by the CRT. It was possible to change the pitch in intervals by varying the Timebase or “SEC/DIV” knob. Through rampant misuse of the calibration knob, I could produce a smooth glissando; its volume could be controlled by moving the photodiode away from the beam. Thus, I achieved the classical “theremin” control of an electronic instrument: one hand for pitch, one hand for dynamics.

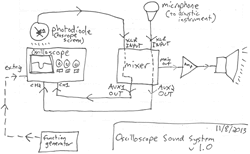

But why not just play a theremin instead of going to all this technical trouble? Unlike a theremin, a gestural synthesizer with simple tonal properties, this system offers unique timbres and melodic possibilities as a result of the interaction of its components. All this “technical trouble” produced an entirely different sound. Without an audio input, the scope would only produce a flat line on its screen. Feedback reveals the intrinsic biases and resonances of any system. With this new electronic instrument, a photodiode and oscilloscope could be used to “look and listen” simultaneously. This was achieved by repatching the oscilloscope and routing the vertical amplifier with an aux send from the photodiode input from the mixer — listening to the CRT beam’s voltage and simultaneously sending it back into itself. By sending the same signal into both mixer and oscilloscope, a feedback path is made entirely in the domain of light, between the screen of the CRT and the photodiode microphone (Fig. 2). As before, the beam ran away from the photodiode sensor. But when pointed slightly away from the beam, the photodiode catches onto lower harmonics of the original sawtooth waveform, resulting in timbral changes and register shifts.

Like all types of feedback, EQing the signal path creates different sonic results. Increase the bass and the scope beam starts stuttering rhythmically. Increase the treble and the noise on the line comes out over the sawtooth sound. To a less predictable extent, adjusting the angle of the photodiode can also control this timbral change. But what makes this system unique, in contrast to the “no-input mixer” type of feedback, is that the scan rate of the oscilloscope asserts itself over the feedback — the pitch set by the SEC/DIV knob dominates; it cannot be corrupted. And so adjusting the EQ and photodiode is almost like changing the stops on a pipe organ.

I built an entire synthesizer system out of four oscilloscopes and a mixer. A commercial modular synthesizer has indicator LEDs, which provide passive representations of the sound being produced. In my system, the oscilloscope shows its own sound, and as I manipulate it, I learn from its light in order to predict its music (Fig. 3). In fact, I often “tune” the system by eye only — adjusting the photodiodes and EQ and only turning on the speakers after it looks interesting. Initially, I considering modifying the oscilloscope for voltage control, in order to interface with modular synthesizers, but the scopes have a number of esoteric inputs and outputs, each of which can be exploited for the manipulation of sound. In the end, I preferred to treat the scopes like found objects, their beams captured and transduced by the photodiode. Each oscilloscope seems to behave uniquely, and thus a mixing of scopes forms a lively ensemble. This version of the synthesizer was built around two models by Tektronix and two by Hitachi. Careful consideration of the mixer was necessary, for the correct number of outputs is needed to route to each oscilloscope in isolation. The mixer is metaphorically the keyboard or controller of this synthesizer, and its fader response and EQ options were important design factors. Ultimately, I settled on a mixer by Mackie, for its compactness and also its parametric midrange; it was also affordable.

The Undertone Series

Look closely at the instrument panel of a Tektronix 2235 oscilloscope. To the left, an illuminated three-inch monitor, lit by a green pixel. Slightly to the right of the monitor, two large knobs (VOLTS/DIV [volts/division] for channels 1 and 2) control the vertical deflection of that line — the vertical amplifiers. These amplifiers are connected to two inputs. To the right of these, the A and B SEC/DIV (seconds per division) knob controls how fast the pixel travels across the screen. Inside the oscilloscope, a trigger circuit aligns the scan rate to the input frequency of the signal present at the vertical amplifier. This circuit is actually essential to display a stable signal that does not wander horizontally on the screen. Modern scopes have an “automatic” setting that allows the user to more reliably trigger with regards to the input signal. However, if desired, one can opt to use an “external trigger” that is accessible by a BNC jack with variable coupling options.

Because the shape of my photodiode feedback is based on the DC offset of that photodiode, the trigger setting doesn’t affect the musical results. And so, in my initial explorations of the musical oscilloscope, I didn't pay close attention to the trigger circuit. But I was curious, and sought to understand this “external trigger” input, so I began by patching to it another aux send from my mixer. Initially, using a sine wave, there seemed to be no change. However, when sweeping the SEC/DIV knob, instead of the coarse glissando I expected, a beautiful, descending minor scale sounded. In fact, upon closer inspection I realized it is not a minor scale, but rather an undertone series — f * 1/n, where n is the undertone and f is the input at the external trigger (Video 2). Some familiar intervals, such as the 4/3 perfect fourth and the 6/5 minor third, emerge from this sequence. Because the undertone series asserts the 4/3 as tonic harmonically, it results in an eerie destabilized feeling, very different formally from the overtone series.

Dead Lion

Realizing that any source could be sent into the external trigger, I next tried my voice — about the furthest thing from a stable sine wave you could get. The scope’s frequency would nudge along with my voice, without me needing to adjust the SEC/DIV knob at all. It was a crude kind of pitch follower, but unpredictable, and sensitive to the range set by the SEC/DIV knob. Singing opened up a new corridor in this practice, which I codified through the creation of my band, Dead Lion. This new project resulted from the zombification of my old solo band, Dandelion Fiction 3[3. Dandelion Fiction consisted of Daniel Fishkin (2005–13) on daxophone, bass guitar, voice and electronics, and Zach Dunham (2011–13) on drums and voice.], recreated through a completely different sound system. The pun in this band name is not trivial — the now obsolete CRT monitor is in fact the dead line. I use the term “zombification” with deliberate reference to “zombie media” 4[4. I first learned of the term “zombie media” from my friend Jason Brogan, who described how CDs and tapes will exist on the planet long after human extinction. See his Operas for Zombie Media for more context.] as first popularized by Garnet Hertz and Jussi Parikka: “dead media revitalized, brought back to use, reworked” (Hertz and Parikka 2012, 425). Though, this term bears some interesting fruit when the project of the musical oscilloscope turns the lab equipment into media itself — instead of being used to debug and create the vessels of music, as would be more expected of the tools of engineering.

Is the fate of all technology obsolescence? In 1932, Bernard London dreamed of an expiration date for products:

I propose that when a person continues to possess and use old clothing, automobiles and buildings, after they have passed their obsolescence date, as determined at the time they were created, he should be taxed for such continued use of what is legally “dead”. (London 1932)

Planned obsolescence was taken not as a mandate by governments, but by engineers, who built and sold products that would force customers to upgrade or perish. A treatise on the ethical horror of this practice is outside the scope of this paper; however, the great oscilloscope, revered in labs across the world, is one stalwart against obsolescence. Tektronix, the most famed brand of oscilloscopes, published thorough manuals containing schematics, layout and assembly diagrammes. If something breaks, it’s usually possible to fix it, albeit very difficult — thus the experience of caring for these arcane machines itself is pedagogical. As long as people are making things, the usefulness of the oscilloscope will endure. 5[5. Let me not put a too rosy-glassed hue on this situation, and describe the problems with mid-80s oscilloscopes: when integrated circuits go obsolete, becoming “Unobtainium”, the machines become near-impossible to repair. There does exist a vibrant culture of hobbyists designing replacement parts for these machines. These replacements are unable to be calibrated, so doing precision measurements is impossible — but the machines function, thus perhaps play, rather than work, is possible.] Legendary analogue circuit engineer Jim Williams writes:

The inside of a broken, but well-designed piece of test equipment is an extraordinarily effective classroom. … The clever, elegant, and often interdisciplinary approaches found in many instruments are eye-opening, and frequently directly applicable to your own design work. More importantly, they force self-examination, hopefully preventing rote approaches to problem solving. (Williams 1995, 5)

This notion of an “interdisciplinary approach” is defined here rather specifically in terms of making circuits for public use — Williams is referring to something as specific as mixing analogue and digital signals on the same power rail. But in terms of making music with oscilloscopes, the term has a different but also salient meaning. Allowing this strange machine into my musical world indeed prevented “rote approaches to problem solving.”

I created Dead Lion in 2013, when I was invited to perform at the Modular Synthesizer Solstice. The idea of an exclusively Modular Synthesizer event simultaneously attracted and repulsed me. I love synthesizers but I had been to these types of events before, and rather than an open situation based on the discovery of new sounds, they have the potential to veer towards the commercial and uncreative. At worst, I feared that such an event would be a hazy, testosterone-filled dungeon in which greasy users showed off their gear. At best, a Synthesizer Solstice could be a creative summit that challenged the limits of what synthesis is. I vowed to perform without a commercial synth, and to make my own using oscilloscopes and a mixer. 6[6. I also use a circuit that causes light bulbs to blink rhythmically, thus causing the photodiodes to behave erratically in the presence of incandescent light. But that is outside the scope of this article. (On the other hand, Michael Vorfeld’s contribution to this issue, “The Light Bulb in My Music,” is, as its title suggests, all about the light bulb. —Ed.)] The oscilloscopes were thus an intervention, intended to break a commonly understood narrative. By definition, synthesis is the combination of ideas to form a system. A true synthesizer isn’t constrained by specific products or fads. By repurposing lab instruments as musical instruments, I was able to show a different perspective on synthesis.

I theorize this project as a band, but it is “dead” — I do not do songs and each performance is a zombie improvisation in which I stagger around for the audience, with no central Urtext. This principle held firm until just recently, when I broke my “no songs” mandate in light of the recent political situation, which compelled me to search for a text. Take for example, MIA, whose subversive messages are couched in readily danceable pop forms. It was around this time that I began to collaborate with Kuhn, a DJ with an encyclopedic knowledge of Electronic Dance Music, from dub to dubstep to brostep. Our collaboration was organic and un-theorized, and I enjoyed talking about music with him. Kuhn sent me audio clips of beats to see how they would interact with the Dead Lion lexicon. As I am not an insider to this type of dance music — it is not my culture — I decided to treat dubstep as a found object, similarly to way I interact with the oscilloscopes. By sending rhythmic content into the external trigger input of my scopes, I was able to make the beams of light dance to the music.

A Repertory Piece: Steve Reich for Oscilloscope

In many ways, what I created as a sound system was the antithesis of a “universal synthesizer” — a machine that can play any music. Rather than the machine being able to play “anything”, it did only one thing, but spectacularly well. That one thing was so rich and exciting that it provided enough play-stuff for many improvisations and theatrical staging. An interview with Pauline Oliveros that I later discovered seemed to capture both my disposition towards my system and my reluctance to compose specific situations for the machine:

I remember a review of I Of IV in some magazine, and some guy was talking about it in very positive terms… but then all of a sudden he said, “Well, it must not be any good, though, because it must have been just thrown together in real time.” That kind of attitude still prevails in an academic sense, that you have to construct these pieces very carefully. Well, I do construct them carefully, but at a very different level… [T]he instrument is constructed carefully, so that I can interact with it at a deep level (Mockus 2011, 29).

It is no coincidence that the Oliveros piece in question, I of IV, was created on lab equipment before the dawn of commercial synthesizers. 7[7. Oliveros talked at length about this piece in her Keynote Address at the 2014 Toronto International Electroacoustic Symposium, “What Matters? Make the Music!,” published in eContact! 17.3 — TIES 2014. —Ed.] The piece is an improvisation that was captured in the studio. Oliveros is very sceptical of the legitimization of experimental work — because the conservative attitude about what constitutes a “serious piece” misses where actual work takes place. I find that the magic of these intuitive improvisations is that something beautiful and fleeting happened and was preserved. But I am not a purist, nor am I nostalgic for a single way of working. I wondered how far I could take the oscilloscopes. Could I do other music on them?

Steve Reich’s Pendulum Music (1966) is a classic feedback piece from the early days of minimalism and process music. In it, microphones swing in pendulum motion by their cables over loudspeakers. While some of the “classics” of the avant-garde might sometimes seem dusty, feedback is always unique in each resonant cavity in which it is sounded. It should never actually get old! In order to add another wrinkle in the story of this piece, I shifted the medium from sound to light. Instead of speaker output, I used my oscilloscope’s cathode ray beam to convert voltage to lights; instead of a microphone, I used my photodiode pickups to convert light into a voltage (Video 5). The SEC/DIV function has been disabled, so the light-photodiode relationship is pure feedback. Besides this, the basic structure of the piece is unchanged. Performers release the microphones from on high to start the pendulum, listen to the resultant sounds until the swinging of the microphones stops, and then pull the power cord to end the piece. I selected two older oscilloscopes with larger screens for this piece, hoping that there would be more visual material for the feedback path. 8[8. My friend Peter Blasser loaned me a special oscilloscope with a blue CRT for this piece.]

There is one complication that breaks the rules of the original piece. In my adaptation of Pendulum Music, the oscilloscopes operate in XY mode, which leaves some unresolved questions about what to do with the other axis. If I didn’t use both axes, the scope visuals would not be so interesting — the screen would display a one-dimensional result. So, I thought to have each scope modulate the other scope, criss-crossing each other through the mixer. Because the feedback is interdependent, the feedback pattern is inherently unstable. This complication doesn’t exist in the score of the piece. However, I don’t think this damages the basic premise of the piece — I hope that this transformation extends the meaning of the piece and gives us another way to interact with the repertoire of experimentalism.

Conclusions

I hope that these solutions might provide inspiration to any experimentalist looking for a new way to see old things. There is still much to be done. Oscilloscopes also contain another input that I haven’t explored thoroughly — the blanking input, which causes the screen to dim. Utilizing this input could inject rhythmic possibilities into my performance. Recently, I have performed this set at parties with a DJ, and I slyly suggested that the DJ send an input to my mixer. When I routed the party-dubstep music to the scopes, I found that it causes the CRT beam to shiver in a lively way.

I take great pleasure in these obsolete, majestic machines. These marvels of engineering are just taking up space in the world, not nearly loved enough anymore in 2017. They come to me from the trash, from friends and from sweet shut-ins that I find on Craigslist. They weigh too much, and though I do worry about the long-term portability of this setup, it works for me right now. Tektronix made some passably lightweight CRT scopes in the 1980s that work well for the job. Gradually, their CRT tubes will dim too much to even be read by the photodiode, and eventually a scope will no longer be useable for performances. I’m lucky to spend so much time with these machines before their bulbs die.

Bibliography

D’Errico, Mike. “Going Hard: Bassweight, Sonic Warfare & the ‘Brostep’ Aesthetic.” Sounding Out! [online blog]. 23 January 2014.

Hertz, Garnet and Jussi Parikka. “Zombie Media: Circuit bending media archaeology into an art method.” Leonardo 45/5 (October 2012), pp. 424–430.

London, Bernard. “Ending the Depression through Planned Obsolescence.” [Pamphlet] 1932. Available at https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/27/London_(1932)_Ending_the_depression_through_planned_obsolescence.pdf

Mockus, Martha. Sounding Out: Pauline Oliveros and lesbian musicality. Routledge, 2011.

Williams, Jim. “The Importance of Fixing.” In The Art and Science of Analog Circuit Design. Edited by Jim Williams. Boston MA: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1995.

Social top