Hearing Loss

London College of Communication (University of the Arts, London) and CRiSAP (Creative Research in Sound Arts Practice)

Text originally published in Leonardo Music Journal Vol. 17 (2007). Republished here with the kind permission of LMJ and the author.

Transferring the emphasis from hearing to loss in the title of this installation results in an interesting shift from a medical or factual orientation to an emotional or philosophical one. Hearing loss is a routine, progressive physical disability; hearing loss is something altogether more nebulous and poetic.

My father died in 2006, leaving behind three pairs of hearing aids and a typically extensive supply of batteries. Hearing aids, like false teeth, are very personal objects that are not only used daily but are actually inserted into bodily orifices. One of the first things that struck me when I began to work with them is that they are made in the shape of my father’s ear canals, giving a positive shape to a negative, internal and intimate space that no longer exists. It was literally through these objects that he heard the world during the final years of his life. Interestingly, his hearing seemed to recover somewhat on his deathbed. We were surprised at his ability to follow conversations we assumed he would not be able to hear without his hearing aids, though we may previously have been misled by the selective nature of his hearing loss when he was at home.

Just handling these objects makes you feel old: your fingers seem clumsy and, unless your eyesight is perfect, glasses or some other magnification are essential, even to insert a battery.

The piece makes use of the minute but complex feedback field produced by what are essentially six tiny microphones and six tiny speakers in close proximity. The feedback produced is relatively quiet but piercing and difficult to localize. When I arrived home in London from Vancouver after my father’s funeral, one of the hearing aids had turned itself on inside my suitcase, and I felt for a few moments like Harry Caul at the end of The Conversation as I searched high and low for the source of the annoying new sound in my flat before remembering the hearing aids in my bag.

Installing the work in Vancouver (1) triggered a bout of tinnitus, my nervous system’s own feedback loop, from which I have still not fully recovered. At the opening, I spoke to Dr Carolyn Hall, who told me about a new kind of treatment for tinnitus called “wearable sound generation”. It uses hearing aid-like devices which, instead of amplifying sound, actually produce tones that are matched to the subjective frequency of the tinnitus. In a recent email, Carolyn went on to explain that the idea is “to cause the higher processing powers (frontal or supertentorial functions) to decide that the sound is inconsequential and thus screen it out. Old versions played white (or pink) noise at a different spectrum than the tinnitus with the aim of masking it, but current thinking is that the timbre and pitches should be closely approximated to fatigue attention. Scratching to numbness, essentially.”

In my work with auditory warnings of my own design, I have sought to draw attention to an abstract beauty in alarm sounds that is usually ignored because of their overwhelming annoyance factor and their association with danger. Likewise, feedback is most often seen as a nuisance and a potential danger to hearing or to electronic equipment rather than as legitimate material for music or art. There is significant interest in feedback in the experimental music community, as witnessed by Knut Aufermann’s special Feedback issue of Resonance Magazine (2002), but the general perception of feedback is overwhelmingly negative. In a recent study at Salford University, it took second place only to vomiting in a list of the sounds people found most upsetting or irritating.

The pitch and timbre of the feedback produced by these devices change in ways that are interesting and difficult to predict, depending on their proximity to each other and the direction in which they face, the size and shape of the space which contains them and the presence and movement of the viewer’s hands or body. Integral noise gates in each device, designed to protect the user from ear-damaging build-up of feedback, mean that rather than unchanging tones, the effect is rather like a conversation between the six diminutive objects as feedback builds up and subsides in complex polyphonic patterns.

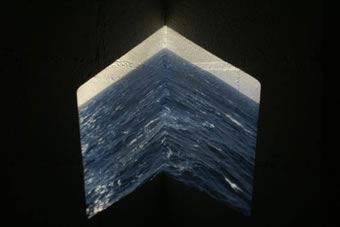

In most of my installation work, the only visual element is the sound-making technology itself, and here I want to let physics and the emotional associations of these evocative objects speak for themselves, but when I looked through Dad’s meticulously organized and labelled slides just before installing, I came across an image I immediately knew belonged in the piece.

It is a shot taken by him somewhere in the middle of the Atlantic. We were on the Homeric, on our way to the port of Quebec City from Europe: I would have been about 2-1/2 years old and this was my first trip to Canada, where I was to grow up. It was uncharacteristic of him to take a picture of nothing but waves, even more so to give it the arguably poetic title Cold Atlantic, and the emptiness of the image speaks of absence or loss in a way that echoes the lack of an active sound source in the piece. And it is an unexpected record of the world seen through my father’s eyes.

Hearing Loss addresses the absence of the person for whom these devices were made, and for this purpose, few sound sources could be more suitable than feedback, which Nic Collins has referred to as “the Zen-like infinite amplification of silence.” Its “tautological elegance” (2) and musical potential contradict its status as problem or systemic fault: in this piece, its antagonistic relationship to hearing aids is harnessed to explore the presence of loss.

Notes

- Signal and Noise Festival 2007 — Lost & Found, held at VIVO (Video In | Video Out) in Vancouver BC, 19–21 April 2007. http://signalandnoise.ca

- Nicolas Collins, “All This and Brains Too: 30 Years of Howling Round,” in Resonance Magazine 9/2 (London: LMC, 2002) p. 6–7.

Other Articles by the Author

“Transplant.” Autumn Leaves: Sound and the environment in artistic practice, Angus Carlyle (ed.). Double Entendre, 2007.

“Language Ecology and Photographic Sound in the McWorld.” Organised Sound 11/1 (2006).

“When Is a Click Not a Glitch?” Sound Art: A Resonance Supplement, Anna Colin (ed.). Resonance Magazine and London Musicians’ Collective, 2006

“Fallender Ton für 207 Lautsprecher Boxen.” Soundscape, The Journal of Acoustic Ecology 5/2 (2004).

“Upcountry: Electroacoustic composition between documentary and abstraction, technology and tradition.” Sonic Geography: Imagined and Remembered. Penumbra Press, 2003

Leonardo Music Journal Vol. 17 (2007): My Favorite Things: The Joy of the Gizmo

If, as Marshall McLuhan so famously suggested, the medium is the message, then the gizmo must be the one-liner. From baroque violinists to laptoppers, sound artists have long fetishized the tools of their trade, the mere naming of which can provoke an instant reaction: Shout “LA-2A,” “TR-808,” “JTM45” or “Tube Screamer” in a room full of musicians, and you will notice the eyes brighten, the breath shorten and the anecdotes pour forth. But only to a point: many a “secret weapon” is held close to the chest. LMJ 17 addresses the significance of physical objects — homemade instruments, effect boxes, pieces of studio gear, “bent” toys, self-built circuits and so on — in music and sound art in a time of increasing emphasis on software and file exchange.

Social top