Sustainable Live Electroacoustic Music

4.3. Boulez, Dialogue de l’Ombre

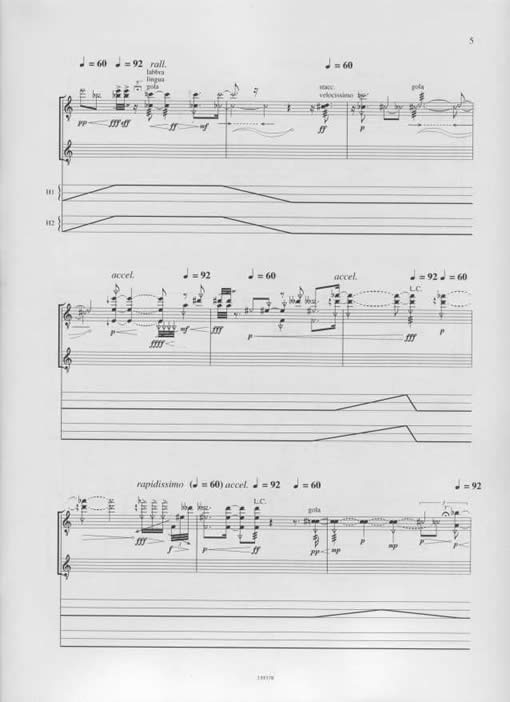

Pierre Boulez’s Dialogue de l’Ombre Double (1984), for solo clarinet and live electronics, provides another brilliant earlier example. The electroacoustic setting implies in this case some special miking of the clarinet, a natural reverberator built out of the resonances of a piano and the performance of a (recorded) “shadow” clarinet in a spatialized context in transitional passages between (real) clarinet solos.

Transition description (example)

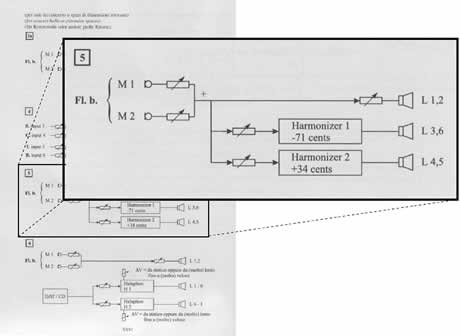

Each passage is described in plain words in a separate part of the score (fig. 5). Levels and volumes of each of the elements are expressed in proportional form in tenths (i.e. 1/10, 2/10, ... ), timings are in seconds, and sound location is expressed in terms of speakers going on or off at given cues in the score (again, in orchestra/score functional distribution — cf. fig. 6). No references to specific technologies are made.

Dialogue de l’Ombre Double is a difficult virtuoso piece both for the clarinet part and for the live electronics part. However, it can be easily picked up, studied and re-interpreted from the score alone (9). There are indeed a few problems in the correct interpretation of dynamic balances (the scales are neither scientific [0dB, −12dB, etc.] nor musical [mf, fff, etc.]), but the overall scheme is very well thought out and it enforces sustainability.

4.4. Nono, das Atmende Klarsein

Luigi Nono’s scores of his late electroacoustic works have always been seriously endangered: the early scores derived from his manuscript were really too scarce in providing information to reconstruct a work from that repertoire. These works could only be performed by an extremely small group of gifted musicians which were personally trained and instructed by Nono for each work, and the electronics were no exception to this.

However, musicians and technicians along with the Archivio Luigi Nono have collected abundant notes and documentation over the years to reconstruct the late works in every details, and when publisher BMG-Ricordi decided to provide a new edition to each of these works, they were ready to answer the call.

Nono’s das Atmende Klarsein (1987) is one of the first examples of this daunting endeavor, and it is indeed one of the most optimal examples so far.

Here too, the score is provided with a detailed description of each processing along with a graphic pattern for performance (fig. 8). In addition, the 2005 edition of score comes with a DVD which contains:

- a historical introduction to the genesis of the work;

- a commented performance (both for the flute and the live electronics parts);

- an audio glossary of flute effects;

- an introduction to the performance of the live electronics part;

- an overview of the performance practices of the choir;

Most comments and introductions are provided by the performers who actually worked with Nono on the première of the work.

It should be noted that the DVD does not carry a simple recording of the complete performance. As stated above (cf. §2), a simple recording would probably jeopardize the possibility of other interpretations. das Atmende Klarsein is the closest example so far to an optimum scoring system for live electroacoustic music. A useful addition could be, here too, the presence of impulse responses for each processing element, and the replacement of references to specific hardware (i.e. the Halaphon — which is nonetheless a well-documented instrument though) with the abstract functionalities of that hardware.

4.5. More Difficult Problems: Spatialization

Representation of sound location in space still remains a harder problem to solve. Solutions such as the one adopted in Boulez’s Dialogue de l’Ombre Double (cf. fig. 6) work for relatively simple movements and settings. When things get more complicated, the space-time characteristic of sound location still poses great challenges to concise symbolic notation that can be learned by performers out of the score alone.

Conclusions

We hope to have raised with this paper the attention over a problem whose solution is ever more urgent: that of the sustainability of live electroacoustic music works.

Since the first draft of this paper we have noticed at least one other paper devoted precisely to this issue (cf. Polfreman et al) in a knowledgeable and documented way. The authors provide interesting case studies of work reconstructions of two complex works by Luigi Nono (Quando Stanno Morendo, Diario Polacco No.2 and Omaggio a György Kurtag). However, these studies concentrate on the technology needed today to reconstruct the pieces, and they fail to consider that the real “infinite” reproduction can only be obtained by creating adequate notation and transcription methods. The authors rely on specific current technology and hardware, thus simply postponing the problem to a later stage, maybe ten, twenty or thirty years from now.

Instead, we strongly maintain that live electroacoustic works will stand a better chance of sustainability if their score will rely upon:

- low technology or no technology at all (paper, ink, standard measure units, etc.);

- redundancy of sources (wider diffusion, perhaps obtained via P2P technologies and open licensing schemes);

- isolated audio and impulse response examples recorded following standardized codings on sufficiently diffused media (such as the CD or the DVD media, though we acknowledge the problems which these media may encounter fifty years from now);

- last but not least, active communities of co-operating performers which will be conscious enough to share and document their experiences (implying of course the ongoing performances of the works themselves).

In particular, any dependency on any form of computing platform and software should be strongly avoided in the scores.

References

Battistelli, Giorgio. The Cenci — Teatro di musica da Antonin Artaud, 1997. Text by Giorgio Battistelli and Nick Ward from the English Version by David Parry, Literal Translation by Myriam Ascharki.

Battistelli, Giorgio. The Embalmer — Monodramma Giocoso da Camera, 2001–2002. Text by Renzo Rosso.

Bernardini, Nicola. ‘Musica Elettronica: problemi e prospettive’, in Tempo Presente, p.89, 1989.

Boulez, Pierre. Dialogue de l’Ombre Double, 1984.

Canazza, Sergio, Guido Corradu, Giovanni De Poli and Gian Antonio Mian. ‘Objective and subjective comparison of audio restoration methods’, in Journal of New Music Research 30:1, pp.93–102, 2001.

Canazza, Sergio, Giovanni De Poli, Gian Antonio Mian and Antonio Scarpa. Comparison of different audio restoration methods based on frequency and time domains with applications on electronic music repertoire, in Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference, pp.104–109, Göteborg, Sweden, 2002.

Eco, Umberto. Trattato di Semiotica Generale. Milano: Bompiani, 1975.

Goodman, Nelson. Languages of Art. Bobbs-Merrill, 1968.

Lazzarini, Victor. A Proposed Design for an Audio Processing System, in Organised Sound 3:1, pp.77–84, 1998.

Lesk, Michael. ‘Preserving Digital Objects: Recurrent needs and challenges, in Second NPO Conference on Multimedia Preservation, Brisbane, Australia, 1995.

Nono, Luigi. Das Atmende Klarsein, 1987 (1st edition), 2005 (2nd edition). Per piccolo coro, flauto basso, live electronics e nastro magnetico.

Marcum, Deanna and Amy Friedlander. ‘Keepers of the Crumbling Culture — What digital preservation can learn from library history’, in D-Lib Magazine, 9:5, May 2003.

Polfreman, Richard, David Sheppard, and Ian Dearden. Re-Wired: Reworking 20th century live electronics for today, in Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference, pp.41–44, Barcelona, 2005.

Porck, Henk J. and Renee Teygeler. Preservation Science Survey: An overview of recent developments in research on the conservation of selected analog library and archival materials. Technical Report ISBN 1-887334-80-7, Council on Library and Information Resources, 2000.

Rothenberg, Jeff. Avoiding technological quicksand: Finding a viable technical foundation for digital preservation. Technical Report ISBN 1-887334-63-7, Council on Library and Information Resources, 1999.

Stockhausen, Karlheinz. Oktophonie, 1990/1991. Electronic Music of Tuesday from LIGHT, sound projection.

Other Articles by the Authors

Bernardini, Nicola and Alvise Vidolin. ‘Recording Orfeo cantando... tolse by Adriano Guarnieri: Sound motion and space parameters on a stereo CD’, in A. Argentini and C, Mirolo (eds.), Proceedings of XII CIM, pp. 258–261. Gorizia, 1998.

Canazza, Sergio, Giovanni De Poli, Drioli C, Rodà A., and Alvise Vidolin, ‘Modeling and Control of Expressiveness in Music Performance’, invited paper, The Proceedings of the IEEE vol. 92(4), pp. 286–701, 2004.

Canazza, Sergio and and Alvise Vidolin (eds.). ‘Preserving Electroacoustic Music’, in Journal of New Music Research Special Issue, 30(4), 2001.

Vidolin, Alvise. ‘Musical Interpretation and Signal Processing’, in Curtis Roads, S. Pope, A. Piccialli, Giovanni De Poli, Musical Signal Processing. Lisse, Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger: 1997.

Vidolin, Alvise, D. Bonsi, D. Gonzalez and D. Stanzial. ‘Convolving a Clarinet with a Piano’. in Proceedings of Forum Acusticum 2005. Budapest, 2005.

- cf. Audio Engineering Society Technical Committee on Archiving Restoration and Digital Libraries.

- The term dense is taken from early semiotic studies (cf. Eco, p.241 and sec.3.4.7; Goodman, III-3; and Bernardini). It basically means documents that carry all the information within themselves, i.e. they are not symbolic representations to be further interpreted and converted into a final artifact.

- Electronic Music Studios.

- cf. for example the Atari Museum’s website

- (Notator Logic being a completely different software running on Macintosh platforms).

- Often the problems are experienced by the composer herself/himself and/or her/his technical assistants when they try to pick up the work for another performance years after the première.

- There are 11 descriptions similar to that shown in fig. 3 and a glossary of 27 vocal effects in the score.

- Notably at the Hebbel-Theater in Berlin in 1999, under the sound direction of sound direction of Mark Polscher.

- Here too, there are many performances by several different players and teams.

Social top