My Personal Long-Playing History of the LP

For the keynote address at the 2016 Toronto International Electroacoustic Symposium, I presented a personal chronology, illustrated by the sleeves of various influential LPs from my personal collection of about 1200 LPs acquired mostly between 1964 and 1972. The first LP era was 1948 to approximately 1989, the latter being also the year of the Canadian Electroacoustic Community organized the >convergence< conference in Banff, and the release of my first CD publication, plunderphonic. 1[1. The term “plunderphonics” was coined by John Oswald in 1985 and refers to the practice of the use, alteration and manipulation of existing recordings to make a new audio work. His essay “Plunderphonics, or Audio Piracy as a Compositional Prerogative” was published in eContact! 16.4 — Experimental Practices and Subversion in Sound.]

In the past decade there’s been a resurgence of interest in and production of vinyl audio, a trend which I’ve joined with the intensifying and augmenting of 1992’s Plexure 2[2. In his 16 June 2017 “review of the release” Volodymyr Bilyk described it as music “that takes a precious fluids out of all sorts of sounds, mixes them together and makes it’s [sic] own brew.”] for the LP prePlexure (2010) and 1995’s Grayfolded as a three-LP set (essentially dividing a 105-minute, two-movement work into six movements, or sides), and the particularly satisfying challenge of adapting the tiny CD art to a panoramic triple-gatefold format. 3[3. See the pFony.com website for more information on Plexure and prePlexure, Grayfolded and other works.] I’ve always thought of the visual packaging and the sound medium, tape disc, file, player piano roll 4[4. Oswald’s work spRite pushes the piano player to its limits with his full — but ferociously sped up — transcription of the four-hand piano version of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du printemps.], etc., as integral parts of a composition.

Some of the albums I’m presenting may seem to have no connection to a tradition that has been labelled with many terms and subcategories, including electronic sound, musique concrète, computer music, electronomusic, electroacoustic, acousmatic or electronica (which leads me to propose a ridiculous but inclusive term, “electronicacousonomaticompcrètescape”). But then my relationship to any of these examples has seldom been traditional.

My presentation at TIES revolved as much around the record covers themselves as about their audible contents.

I intentionally avoided the set sequence of a PowerPoint-style presentation, preferring the greater freedom of selecting items from my bin of records — out of sequence if such was dictated by the extemporaneous narrative — and a give-and-take with the audience. But, more importantly, this gave that audience a sense of the physicality and the history of wear on these illustrated cardboard encased vinyl objects.

I’ve often thought of myself as an active listener — interested in the possibilities of listening differently, and in applying this aural curiosity to changing how sounds sound. As the following chronological sequence progresses, I begin to mention my more active intrusions into the making of recordings and records.

A Chronophonography

Dates indicate the year of the LP release, which sometimes follows the composition dates by several years.

In 1947, Bing Crosby rerecorded his 1942 hit White Christmas, the original master recording having been damaged by frequent repressings. It has become the best-selling single recorded song ever. In the same year, Crosby purchased the first two tape recorders manufactured in North America, mostly so his regular radio broadcasts could be edited and time-shifted, two functions which, in the coming decades, would transform studio composition and the consumption of media, respectively.

The modern LP was introduced in 1948, the same year Pierre Henri Marie Schaeffer broadcast his first examples of musique concrète. Although phonographic records were Schaeffer’s means of reproducing and altering “sonorous objects”, it was years before his compositions were released in this form: the compilation album Panorama of Musique concrète (released in 1956, but works date as early as 1948) also includes the prolific Pierre Henry. These gentlemen initially altered sounds chiefly through the manipulation of phonograph records. It would be another decade before I created my first concrètionary sound experiments, utilizing both vinyl and tape.

Les Paul was not the first person to overdub himself playing musical instruments, a notable precursor being Sidney Bechet, who in 1941 visited a studio to record a pair of six-part, one-man band tracks. With recordings such as The New Sound! (1950), Paul did, however, popularize speed shifting — recording at a speed slower than playback creating both a timbral shift and an artificial virtuosity — and double tracking, which revealed that one singer recorded multiple times, in harmony but especially in unison, sounds quite different from an ensemble of individual singers. Approximately four decades later, Paul Dolden became the indisputable king of multitrack instrumental overdubbing.

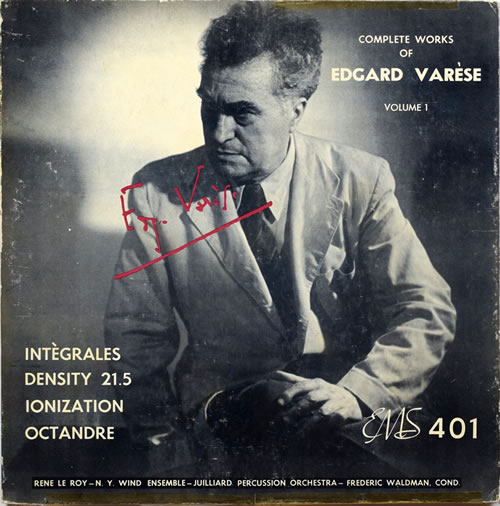

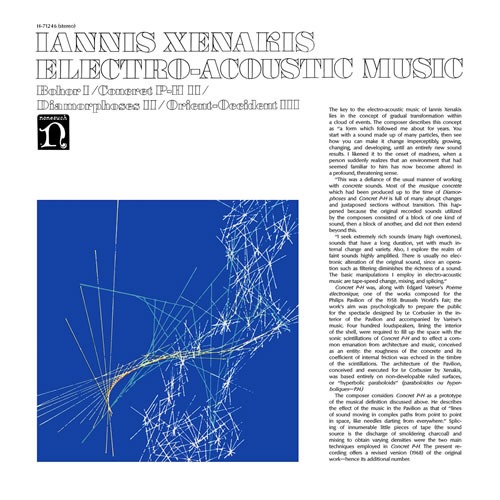

In 1953, the year I was born, a 13-year-old Frank Zappa read in a magazine about one of the odder items in a NYC record store: an Edgard Varèse album. It took another year or two for him to find a copy of the LP of the Complete Works of Edgard Varèse Volume 1 (1951). The four selections are all instrumental concert pieces, but Varèse, with his concept of “organized sound”, more than anyone foreshadowed the sound studio manipulations of the future. Varèse and Iannis Xenakis both had spatialized musique concrète pieces playing in the Philips Pavilion (which was chiefly designed by Xenakis) at the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958. Toronto-based composer Udo Kasemets witnessed this presentation.

Karlheinz Stockhausen premiered his seminal electroacousmatic work Gesang der Jünglinge (1955–56) on my third birthday. Kontakte (1958–60) followed a few years later. In the late ’70s, in San Francisco, I was approached by a fellow named Peter Plonsky who proceeded to vocally recite a recognizable facsimile of Kontakte.

I’ve never seen a copy of the reel-to-reel tape release (a commercial format first introduced in 1949) of Deutsche Grammophon’s 1962 reel-to-reel release of the two works, misleadingly labelled as “4-track”. In fact, it is two-track stereo in one direction for Gesang der Jünglinge, which was conceived in five channels, and then two tracks in the other direction for the composer’s stereo mixdown of Kontakte. I have speculated that Stockhausen’s preferred configuration for the 4-channel Kontakte 5[5. See Kevin Austin’s analysis of “‘Kontakte’ by Karlheinz Stockhausen in Four Channels” published in eContact! 12.4 — Perspectives on the Electroacoustic Work.] would have been a cross with speakers directly in front, behind, and pointed at the ideal listener’s left and right ears. The composer specifies that the loudspeakers be placed in the four corners of a room, so I would suggest then that the audience be situated on a 45° angle.

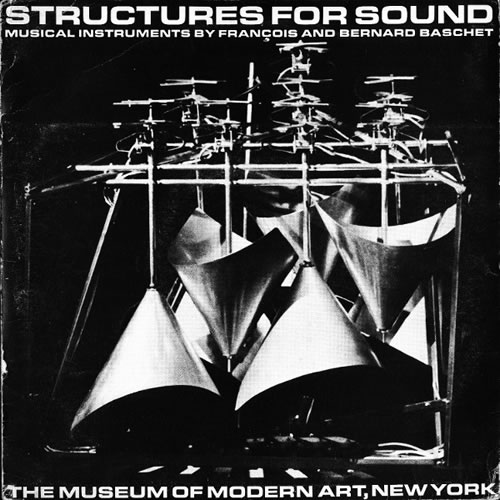

The Baschet Brothers made the first of three appearances on the Ed Sullivan TV show on Sunday, January 20th, 1963, as The New Sounds (French instrumental quartet). Ed Sullivan told them, “Play well but play fast, for in our modern childish society, the public’s attention span lasts only four minutes.” Their second appearance was on November 17th, 1963. I particularly remember the playing of glass rods with wetted fingers on instruments sprouting metal sheets rolled into resonating cones which all looked very sci-fi, and produced sonorities which were later echoed in the sound of Toronto’s Glass Orchestra. Glass Orchestra cofounder Marvin Green eventually visited François Baschet and adapted Baschet’s inflatable folding guitar (1952) as an inflatable folding double bass. Our family watched the Ed Sullivan Show every Sunday evening. The Beatles made their first appearance on February 9th, 1964.

As I began to hunt for records of new sounds I usually had, in a sense, to be able to “read a book by its cover.” The records were all shrink wrapped in plastic, and few, especially the rarer and odder ones, couldn’t be listened to before purchasing. A trip to London, England in 1969, revealed that the discs in stores there weren’t shrink wrapped, and could be auditioned in playback booths, before purchasing. This was a revelation and a listening cornucopia, only surpassed by the University of British Columbia record library, where one could grab any album from the bins and take it to a listening kiosk. Someone might remember seeing me there in the early ’70s trotting torso-length stacks of albums under my chin to a listening booth, where I would hunt and peck through my skyscraper of sound.

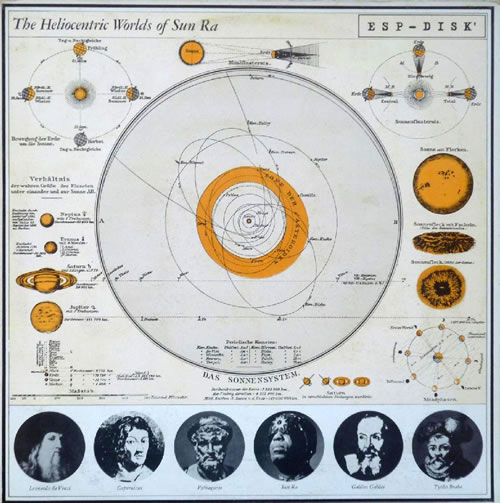

In the mid-60s there began a trend, outside of the Classical music world, towards the extinction of liner notes — a drastic reduction of information for at least a few years before the widespread introduction of rock journalism. By 1965 I was frequenting The George Kadwell Organs and Records store in a mall in downtown Waterloo, where the most intriguing LP package in the bins was The Heliocentric Worlds of Sun Ra, Vol. 2 (recorded in November 1965 and released in 1966), on ESP-DISK. Sun Ra himself is depicted between other notable astronomers, with Pythagoras on his right and Galileo on his left. But the sticker price for this lone album was a premium $5.35, and not having any idea of whether I would like the music or not, its acquisition was delayed for another couple years.

On the back of the sleeve Sun Ra is holding an instrument which appropriately looks like a more delicate version of the sunburst wall clocks popular at the time, not to be confused with the popular sunburst finish on electric guitars.

Heliocentric Worlds, Vol. 1 (1965) featured an impressively recorded bass marimba, better recorded than Harry Partch’s even deeper “marimba eroica”. Partch had for many years been creating his own instrumental universe distinct from the similarly iconoclastic Baschet Brothers and Sun Ra, and his book Genesis of a Music, could be found at our local library.

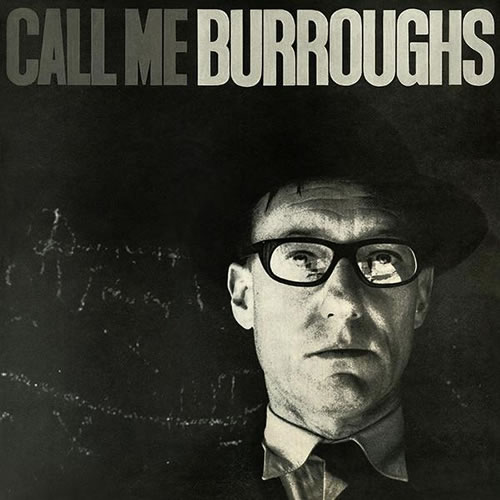

Call Me Burroughs (1965 in Paris; 1966 in New York on ESP-Disk) is a perfectly simple documentary recording of one reading voice, monostomatic 6[6. “Monostomatic” was a variation on “monophonic” that I applied particularly to the Burrows suite. “Stomatic” comes from Latin and is used most often in reference to diseases of the mouth, an association that seem to resonate with Burrough’s style of writing. Perhaps influenced by the preferences of Phil Spector and Brian Wilson, I tended, back then, to work in mono.], embellished only by an approximately 200 ms mild tape delay, but for my 14-year-old self this was a heady advocation of a compositional method of chopping texts into fragments, here pronounced in the author’s ominous metallic croon. This eventually led to my convoluted reconfigurings of snippets of these recordings.

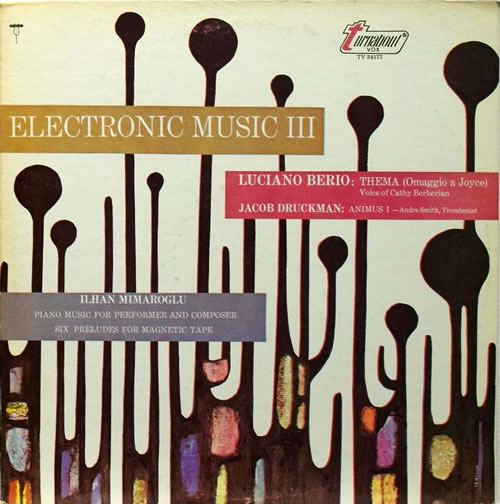

On a visit to the great Sam the Record Man store in Toronto I acquired Electronic Music III (1967), which contains the late ’50s Luciano Berio electroacousmatic composition Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) — for me the clearest introduction to the transformational and not merely documentary possibilities of recording studio shenanigans.

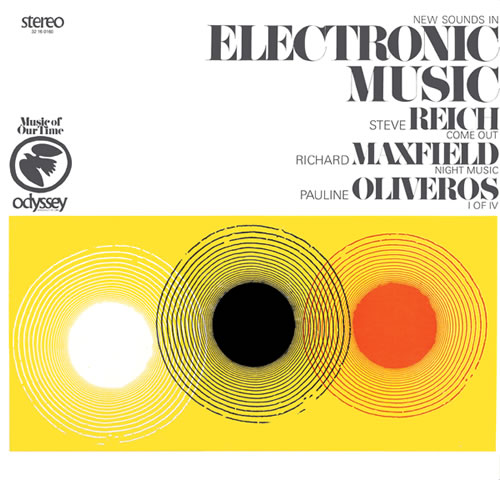

New Sounds in Electronic Music (1967), purchased the same trip, is a substantial triple bill. The playback of Steve Reich’s Come Out was not encouraged in our home. The tape-phase effect was influential nonetheless, and several years later, for my Burrows series, I reconfigured this technique, as a deconstruction rather than accumulation, in Word Falling, using those two words spoken in Call Me Burroughs.

Richard Maxfield’s Night Music title does lead one to hear this as a tone poem. A handful of evolving twitterings are the audible difference patterns produced by pairings of ultrasonic signals. Pauline Oliveros’ I of IV uses similar sources, but with the addition of long tape delay loops adding the dimensions of echoed past time, and spatial depth totally unrecognizable from the basement Electronic Music Studio at the University of Toronto where she created it in the summer of 1966. 7[7. For more discussion of this piece and the UTEMS studios, see Oliveros’ TIES 2014 Keynote Presentation, published in eContact! 17.3, “What Matters? Make the Music!”]

Edgard Varèse died in late 1965. By the summer of ’66 I was reading in the notes of Frank Zappa’s first release, Freak Out! the Varèse quote, “The present day composer… refuses to die.” We’re Only in It for the Money arrived in late 1967. More startling than Zappa’s orchestrations and his musique concrète fragments was his use of juxtaposition, collaging a wide range of musical sources and styles into a many-faceted parade.

I’ve selected this particular Zappa release because of its cover, which was presented as the right-hand inside of gatefold jacket that, when bent in half the other way, became a parodic facsimile of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, released six months earlier.

My first visit to Expo 67 in Montréal was a few days after it opened in April. The long line-ups had yet to develop and so I covered a lot of ground in a few days, including multiple visits to the French Pavilion (now the Montréal Casino), where there was an atrium-filling sculpture of floor-to-ceiling cables — a suspension bridge gone askew — designed by Iannis Xenakis, with flashing lights and electronic music also composed by him. I remember noting at the time that it wasn’t the cables that were making the sound but hidden loudspeakers, and that the sound and lights seemed to be independently active. I associated the look with the instruments of the Baschet Brothers, but thought that this wasn’t integrally “sound sculpture”, wherein the object you see is making the sound. Sound sculpture wouldn’t have been a term I would have been using back then, but nonetheless it was a distinction I was aware of.

In 1973 I was trying to develop what I thought of as an electronic sound sculpture, where the sound didn’t change with time, but rather with the changing position of a mobile listener. The elements for this became my monophonic and stereo electronacousmatic composition Vertical Time.

A series of discs produced by Philips (the company that hosted the Xenakis-designed pavilion at the Brussels World’s Fair) for their “prospective 21° siècle” series (1967 onwards), with their textured foil jackets, visually stuck out on the shelves at Sam the Record Man’s, but I didn’t buy any at the time, because of their premium import prices. I opted for the bargain-basement prices of the North American versions of a lot of the same music. But the Philips covers reminded me of the Baschet instruments and the Expo 67 sculpture by Xenakis.

I found Intersystems’ Peachy (1967) in the summer of 1968 on sale for ¢88 brand new (without even a delete punch hole) at the Canadian National Exhibition. With such an intriguing cover painting, how could I resist? The back cover listed the participants but no instrumentation. Still, I think it was no great surprise that one of them, John Mills-Cockell, played synthesizer. Another was a poet who did not sing. Within a year they performed, at the University of Waterloo, a multimedia show, with a light show and projections and sounds and poetry, from a scaffold cage in the middle of a room. Mills-Cockell played a modular Moog, the first I’d seen in real life, and perhaps one of the first live performances with that instrument.

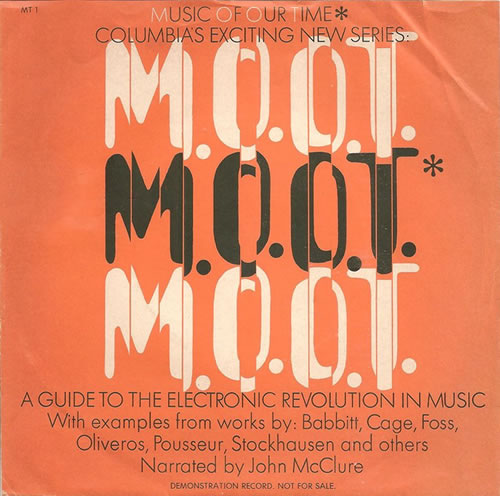

I received by mail order request (and quite possibly for free) the sampler M.O.O.T. (Music Of Our Time) — A Guide to the electronic revolution in music (1968). Released by Columbia, this “Exciting New Series” contained works by Stockhausen, Dylan, Foss, Cage, Babbitt, Pousseur, Maxfield, Oliveros, Reich, Lucier, Kagel, Wolff, Ichyanagi and others, performed by The Byrds, New York Philharmonic / Leonard Bernstein, David Tudor, The Brandeis University Chamber Chorus / Alvin Lucier, The Chambers Brothers, Moby Grape and others.

Many years later I reconfigured John McClure’s spoken introductions and panmusical philosophy, for introduction to what I thought of as an even broader scope of the possibilities for sounds in recordings, but also as an homage to this delicious 7-inch EP.

I realize now that I’ve often referred to Mauricio Kagel’s composition Improvisation Ajoutée (1962) for organist and two assistants, based entirely upon the brief passage on this disc, where one hears the assistants madly cackling as they pull out the stops in what sounds like a massive instrument. To this day, I have not heard the rest of that performance, but have an idealized version which occasionally plays in my head, based on this fragment.

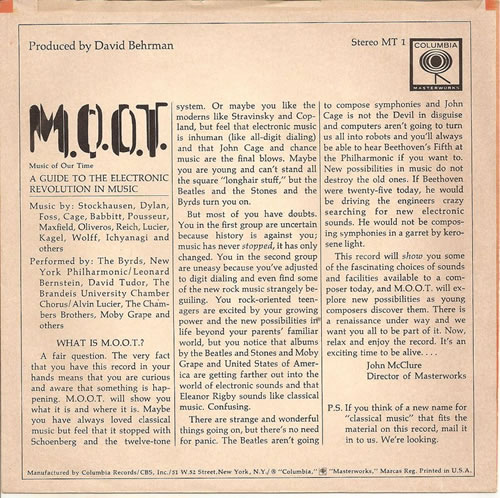

Hymnen (1966–67, rev. 1969) was preceded by Telemusik (early 1966) as the first of Stockhausen’s blatantly “plunderphonic” pieces (two decades before I coined the term). With its anthems emerging from a short wave soup (I’d been tuning and listening endlessly to the sounds in that realm since I discovered the short-wave band on my first transistor radio near the beginning of the ’60s), it’s electronic roars and tunes, aural illusions (a flock of birds slows into a crowd of humans, slowing further into a gaggle of geese singing La Marseillaise), and my first encounter with the potentially infinite descent of Shepard tones (to be countered by the ascending sense of Jim Tenney’s For Ann (rising) in 1969) it’s easy to get lost in Hymnen. I don’t remember if this gave me the notion that there might be a moral licence allowing one to turn existing music into something else, but Stockhausen himself, in a personal Xmas card years later, warned me not “to touch other works which are the messages of other souls.”

Regardless, I do…

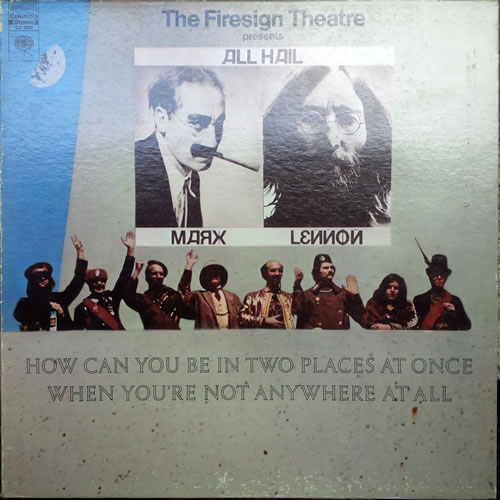

I totally missed out on the Goon Show in the ’50s and early ’60s, knew nothing about Beatles producer George Martin and Stanley Kubrick’s multiple personality star Peter Sellers being involved with them, but at least I found Firesign Theatre’s records in timely fashion. One side of How Can You Be in Two Places at Once When You’re Not Anywhere at All (1969) ends with a gender-shifted recitation of the closing Molly Bloom monologue from James Joyce’s Ulysses (directly connecting them in my teenage pantheon to Berio and Thema) and on the other side there’s a moment where the radio drama character Nick Danger, Third Eye says, “Wait a minute… didn’t I say that line on the other side of the record? Where am I? I’d better check” — parting the vinyl curtain. He hears, reversed, the counting cadence of a military march, which, yes, you can find playable frontwards on the other side of the record (but, I just discovered to my disappointment, the physical alignment in the grooves is off by about an inch).

To hear a voice announcing its phonographic self-awareness was thrilling. This is just one of a myriad of twists on time, memory and repetition that happen throughout this influential spoken word group’s records.

By this time I may have acquired a fascinating Xenakis record featuring his three orchestral works Metastasis, Pithoprakta and Eonta (on the Vanguard Cardinal Series) but hadn’t heard any of his other electronic music.

A major distraction in listening to recordings on vinyl pressings, especially recordings with a wide dynamic range, was the added patina of turntable rumble, dust mote tics and the occasional scratch. Xenakis’ studio composition Concret P-H II seemed like the ideal piece for vinyl. The record noise when playing Iannis Xenakis — Electro-Acoustic Music (1970) just adds to the overall physical impression of the tinkling, crackling embers of this somewhat steady-state sound world.

Concret P-H was also featured in the aforementioned 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, Philips Pavilion.

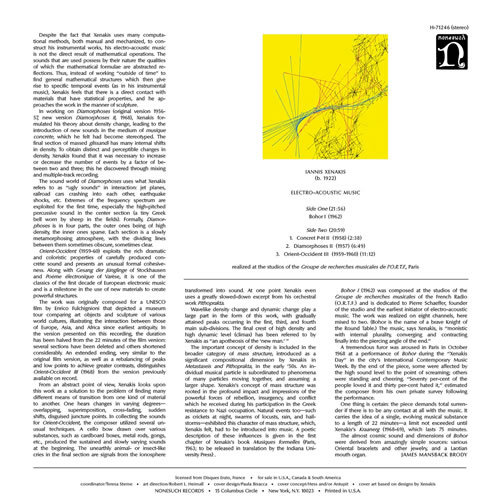

In the summer of 1974, I worked for Our Murray Schafer’s World Soundscape Project at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. The pure recordings of common and rare sonic events, both man-made and otherwise, to be found in the WSP Archive, on The Vancouver Soundscape (1973) and particularly in a series of extremely creative radio programmes developed for Ideas on the CBC, were thought-provoking and beautiful contrasts to the more abstracted sound constructs of much of my record collection.

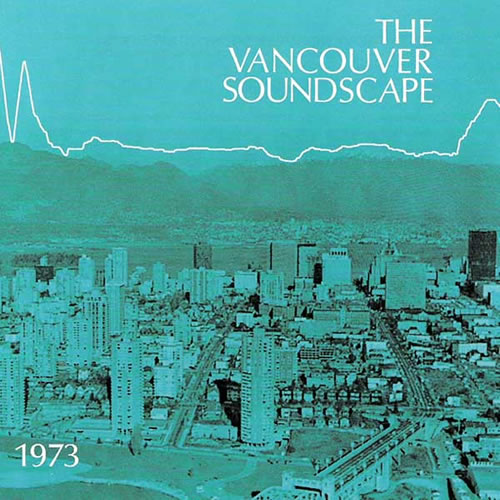

As a big fan of the Nonesuch record covers with liner notes beginning on the front face (see also the cover for Xenakis’ Electro-Acoustic Music, above) I found the packaging for Michael Snow’s Musics for piano, whistling microphone and tape recorder (1975) extra appealing — it was all liner notes, with the print getting smaller and smaller on each progressive face of the gatefold cover for this double record set. The three pieces found therein were equally fascinating, especially Falling Starts, in which a brief recording of a Snow piano improvisation is played repeatedly, each time at half the speed of each previous iteration, until finally the lowest and slowest takes up a whole record side.

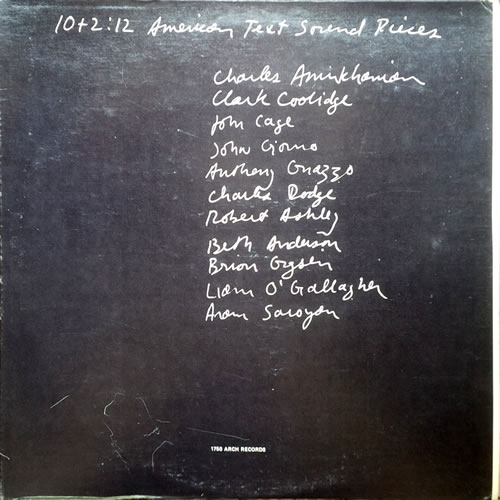

My major opus during my Vancouver sojourn was the suite of short pieces known then as the Burroughs Tapes. As with Berio’s Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) (1958), I found more comprehension in the musical possibilities of spoken words, than in any other sound or music. In Charles Dodge’s Speech Songs, on the compilation disc 10+2:12 American Text Sound Pieces (1975), the computerized voice, is, to my ear, an amalgam of Douglas Rain’s voice of HAL, and Walter/Wendy Carlos’ vocoded Ode to Joy created for two successive Stanley Kubrick movies, both recalling the 1961 computer vocal rendition of Daisy — the sound of any of these still makes me “half-crazy”.

The jacket notes for On Being Invisible (1977) read: “live at the music gallery / toronto / 12 february 1977 / A solo electric concert utilizing hybrid-computer wave analysis and sound synthesis, brain signals, touch sensors, and small acoustic sources /.” I was at this concert, which was delayed by two weeks when Rosenboom’s whole system crashed just before the original concert was to begin.

The music required very little visible activity from the performer but was obviously intimately responsive to his minimal actions.

The Glass Orchestra (1978). I was a founding member and for a very short time a performing member of this all glass instrument improvising ensemble, which initially scrounged sonorous glass objects: goblets, bowls and shards; followed by the building of glass marimbas and blown glass wind instruments; eventually adding a couple of Ben Franklin glass armonicas.

Also note, this LP was pressed on clear vinyl.

For his 1979 release Lyra, David Keane provided the striking photograph of Racal Zonal audio tape with its powder backing — the first time I’d ever seen this formulation, short strips of which I have for years used as bookmarks. I designed the package, a task which mostly consisted of making sure the tape looked life-size in its 12-inch square, and carefully choosing the trim and letter colours, the titling being a very un-electronic-age old Gothic lettering, which I thought blended suitably into challenging legibility. I was, and am, extremely pleased with this design, but David sadly was less convinced that obscure music should have similarly obscure “signage”.

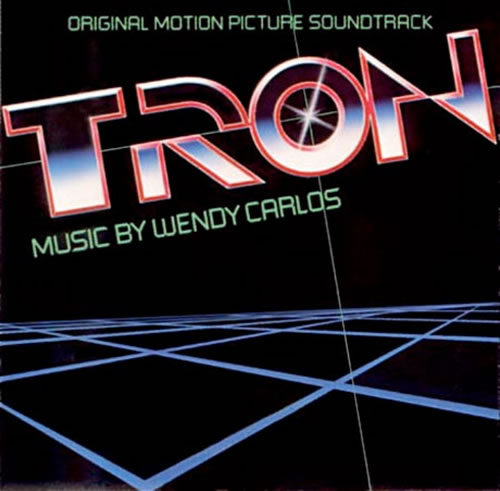

Wendy Carlos’ electronic arrangements transformed a few Classical music classics into the sound of a fictional near-future age for Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. For Tron (1982) she wrote a number of orchestral cues which were recorded by a live orchestra in a traditional fashion. She was so disappointed with the sound and performance of the results that she created analogue synthesizer reinforcements very carefully matched in time and timbre. Some of the cues, representing an inside-the-videogame viewpoint, are more electronic, and others, taking place in the “real world” of the film, are more quasi-acoustic, blended with a subtlety which has rarely been matched.

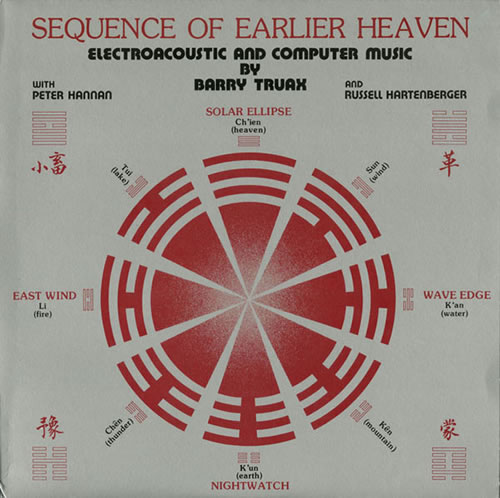

When I first met Barry Truax in 1973, it was his first term teaching at Simon Fraser University. Back then he was composing with POD and PODX computer music systems — he still does, with ancient computers. Solar Ellipse, from his 1985 album Sequence of Earlier Heaven, is still my favourite example of arguably the dominant new-sounding technique of the ’80s: frequency modulation. I was oft overheard back then grumbling about how the most popular FM instrument, the Yamaha DX7, exhibited less timbral variety than an oboe.

Barry, with 1986’s Riverrun (James Joyce again) is a pioneer of the granular synthesis technique, which, when used sparingly, can achieve plunderphonic results.

…

You may have noticed that several years separate each of my last few choices. I’d mostly stopped buying records by the late ’70s. Starting in 1972, I began archiving short fragments of sound and music to cassette tapes, and edited and mixed and even performed mostly on reel-to-reel. My first published release was Burrows (1974–75), on a 5-inch reel full-track mono, with each piece separated by paper leader, and some of the pieces were chiastic, or reversible. But no one ever bought a copy.

In the late ’70s I was producing records for other artists, and as a component in the playing and postproduction of improvised music, on occasion subtly subverting the prevalent documentary nature of most improvised recordings.

About that time some of my other experiments were incorporated on cassette as a corollary to the print Musicworks, I developed and curated a “magazine in sound” (quarterly 1983–86), and through a more enigmatic production process, Mystery Tapes, of which, by their intent and very nature, I cannot say more…

Christian Marclay’s Record without a Cover (1985) was perhaps the most blatant published conflation of the concept of a phonodisc as a playback medium, an impermanent object, and a source of sound in and of itself, taking the notion I had of Xenakis’s Concret P-H being unwittingly a good marriage between the “noise” of a record and its signal, and making that marriage intentional. The “liner” notes were embossed in circular lines on one side of the bare record, with the specific instruction: “DO NOT STORE IN A PROTECTIVE PACKAGE.” The opposite side of the disc had a groove which could be played on a player in a conventional fashion (the standard speed of 33-1/3 rpm was specified), wherein the content is a mix of several sources of record noise, which is further embellished depending upon how willfully careless one is with the product.

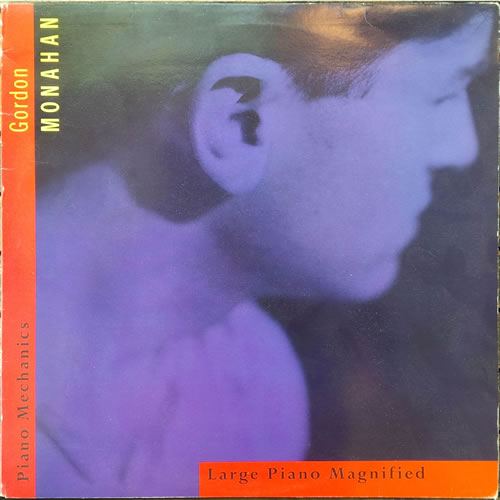

With Piano Mechanics (1986), Gordon Monahan had many listeners imagining electronic processes being applied to the sound of an acoustic piano. A few years later, with me producing, the piece was re-recorded for CD. The production marks the first, and I think most successful, use of the O.M.N.I.V.E.R.S.E. technique, which I developed specifically for documenting this piece. 8[8. The Orbital Microphonic Navigational Imaging Via Ecotonic Radial Stereo Eccentricity is a technique developed by John Oswald for recording with a moving microphone in a panoramic field. More information can be found on the “Mystery Lab” section of the plunderphonic website.]

Large Piano Magnified (1985), on the verso side of this LP, features Gord applying studio tape manipulations to his piano recordings. As is the case with a few of the other items mentioned here, this piece has never been rereleased in another medium, and is currently hard to find.

Epilogue

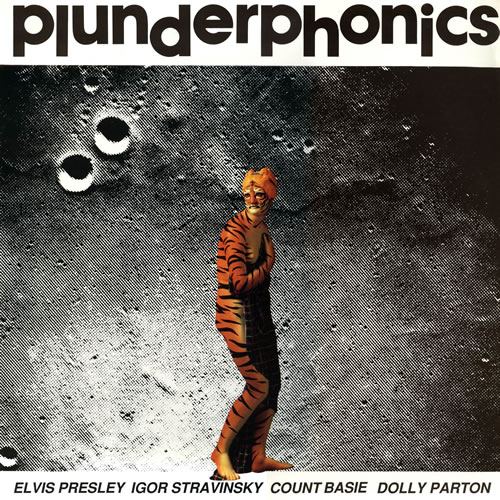

In 1988 I finally got around to producing the first vinyl record I really considered my own. I was able to overcome the general trend of plummeting sales of vinyl by distributing all copies of this 12-inch EP for free. I say this is my first release, but my name is not mentioned on the front cover (which I designed, with the Tiger Lady, a sculpture painted by Byron Werner). As in any plunderphonic work, the final form is obviously appropriated from a familiar existing music, and those obvious sources — for the four pieces on the disc Elvis, Igor, the Count and Dolly — are recognizably present, alerting potential listeners to approximately what they might hear. Identifying the sources up front hopefully increases the surprise of how these sources have been transformed.

Among the unusual features of this package were a range of recommended playback speeds for some of the tracks; the widest spectrum being for the Stravinsky reconfiguration, Spring. My great preference, as a kid, was to listen to a 33-1/3 Rite of Spring disc at 45 rpm, or even at 78. I eventually acquired a Swiss Lenco-Bogen turntable which could be tuned to an infinite range of speeds, from below 16 rpm to well above 78 rpm — this ability was instrumental to creating the middle section of the Dolly Parton track.

Another project that I was working on contemporaneously was based on a recent Michael Jackson recording. That track, Dab, was released on Hallowe’en of 1989 on the first plunderphonics CD (Video 2), which included White, germinated from Bing Crosby’s White Christmas, mentioned above. 9[9. All the contents of that “repressed” disc were later released in the 2-CD+book package 69plunderphonics96.] Dab had its public debut in November of 1989 at the CEC gathering in Banff, >convergence<.

By this point in time I had completely abandoned acquiring, listening to and using vinyl records. Seven months later my studio became predominantly digital. I kept the analogue equipment and still use it when nothing else will do the job, or as good a job.

It would be another twenty years before I returned to record production.

One more subjective note: one of the greatest challenges and tribulations of record production is the lacquer mastering stage. Getting a good pressing for a small run of a title was a crap shoot: sometimes the pressings sounded like crap. But prior to that often unfortunate outcome, if the producer had an attentive relationship with a lacquer-mastering engineer, the tricky transformation of sounds on tape to sounds in grooves could yield agreeable and sometimes enhanced results. So, I was present for lacquer mastering whenever possible. In contrast, the exact replication of a digital sound source of equal sample and bit rate to a standard CD is an expected and most often achieved result. 10[10. Although, I once travelled to a major CD replication plant to find and replace a faulty cable which had added a subtle additional sound component to possibly scores of releases, including the one I had produced. There was a periodic tapping heard on the CD accompanying the high notes of a flute solo, a tapping which did not exist on the master tape. The plant engineers initially suggested that the flautist in the recording was perhaps tapping her foot…] But in 2010, for a small run of the LP prePlexure, I sent a master file through a broker to an anonymous, and possibly indifferent lacquer-mastering engineer at a bulk production studio in California. Given the robust nature of the tracks (distilled mostly from pop recordings from CDs culled from the ’80s, the decade of vinyl’s precipitous decline) and the relative brevity of the sides (under 15 minutes) ensuring a high signal to disc noise ratio, I thought the results might be acceptable. Shortly thereafter I received a test pressing, which I put on an ordinary DJ turntable wired into the playback system I had mixed and mastered the material on.

Now at this point I should probably state that, in spite of spending the majority of my ongoing formative years listening to and producing music on vinyl, I was not, in particular, a fan of the sound of recordings on phonographic discs, examples such as the Xenakis and Marclay I mentioned being the rare exceptions. When the opportunity to switch to digital came I nary listened to any records in my collection (but neither did I replace them with CD rereleases).

So I dropped the stylus on the prePlexure platter, listening to the same playback system through which I’d been hearing its ongoing revisions and transformations for the 17 years past. And I had the shocking impression that this offshoot of the original master sounded in some ineffable way better than the original. More pleasurable.

I am aware that the vinyl disc is always an at least slight distortion of a source. In this case it is therefore a distortion of a familiar source — one which has been meticulously fine-tuned to my inclinations of quality — but there’s something perhaps flexible in the nature of the vinyl playback medium which makes it a joy to listen to.

PS

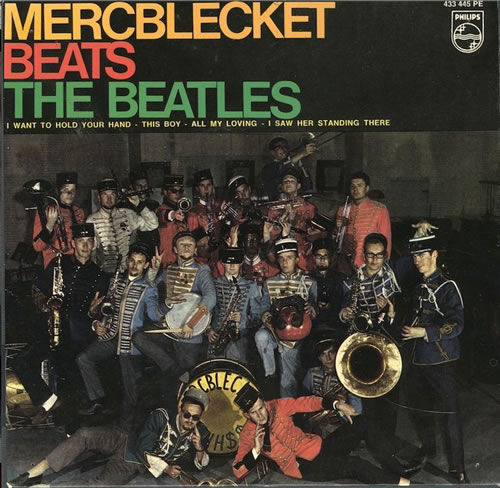

I’ve edited out two early, Beatles-related items which have sent me down a seemingly endless rabbit hole of associations, most recently discovering Mercblecket Beats the Beatles (1964) by a Swedish brass band, the somewhat familiar cover predating by three years Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which features images of Karlheinz Stockhausen and William S. Burroughs, both of whom are discussed above.

Social top