Conversation with Eric Salzman, Music Theatre Composer and Producer

WBAI Free Music Store and dark, dark nights at the Electric Circus

The interview that is the basis for the following text was done by telephone on Sunday, 16 November 2008, with Bob Gluck in Albany NY and Eric Salzman in Brooklyn. The author has reworked the transcript of the interview as a first-person text.

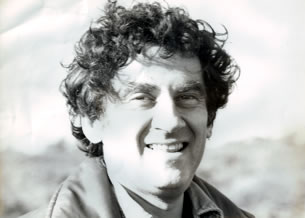

Eric Salzman is a composer, writer and musical producer. He is best known for his New Music theatre works, small-scale multimedia vocal productions that engage extended vocal techniques and amplification. Salzman has referred to this evolving genre as “the off-off-Broadway of opera, the equivalent of modern dance as opposed to ballet.” During the 1960s, he served as Music Director at Pacifica station WBAI in New York City. His production work has included programming at the WBAI Free Music Store, The Electric Ear and New Image of Sound. Salzman is founder of Quog Music Theater and American Music Theater Festival. His books include The New Music Theater: Seeing the Voice, Hearing the Body (with Thomas Desi) and Twentieth-Century Music: An Introduction.

http://www.ericsalzman.com

Early Career, Teaching Positions and WBAI

I graduated from Columbia University in 1954, completed an MFA from Princeton in 1956, had a Fulbright in 1956–58 and, upon my return to the States, immediately landed a New York Times music critic job, which I did from 1958–1962. In ’62, Harold Schonberg, then newly chief critic at Times, fired me because I was a composer; he didn’t think that critics should also be composers. In 1964, I was hired by Alan Rich at The Herald Tribune and wrote for it until 1967. During one of those Tribune years, I was in Europe on a fellowship, although I did a lot of writing from there. I was working at The Tribune when it collapsed; I was on the picket lines. After that, I stopped being a critic, although I continued to write for Stereo Review and other audio magazines.

I taught for two years at Queens College, in 1966–68 and I was involved with the founding of the music theatre program at NYU, where I was the “token avant-gardist” for a bit. Previously I did that stint at the Yale School of Music when Oliver Knussen didn’t show up; that’s when I suggested doing a course in new opera and music theatre. The composition students all showed up with collaborators from Yale Drama! I also did a guest stint at Hunter somewhere along the line but that was not connected with the Hunter New Image of Sound. Other involvements included Quog Music Theater (1970–82) and American Music Theater Festival (1982–1994/95). I was also music director at New York listener-supported radio station WBAI Music from 1962–64 and returned to it again 1968–1972, during which time I was founding producer of the WBAI Free Music Store.

The Hunter College Series

The New Image of Sound series came about because the guy running the music series at Hunter College was interested in doing a contemporary music series. I proposed one involving with what we now think of as performance art, the use of visual and theatrical elements to amplify the abstract and stiff contemporary music of the day. This is the origin of the title. The series began in 1968, in the second year of the Electric Ear series; both ran for only two seasons. New Image of Sound was an intentionally eclectic and mixed bag of programming, including all sorts of people and even experimental jazz. Lalo Schifrin, Ornette Coleman, Gunther Schuller, the nascent Julliard Players under Dennis Russell Davies, and many others played shows. The series took place at the old Hunter Playhouse before it was remodelled and renamed the Kaye Hunter Playhouse.

One of the concerts was Dennis Russell Davies conducting Berio’s Laborintus II, coupled with the world premiere of my own Foxes and the Hedgehogs, which had a text by John Ashbery. In 1967, we programmed Sal Martirano’s L’s GA, which included somebody in a gas mask. Also in the series was enigmatic jazz musician Ornette Coleman, who had at least half an evening, which was a fairly big deal. Gunther Schuller also did a concert. Overall, those concerts were pretty special, unique events and, I believe, all of them were reviewed.

The WBAI Free Music Store

I was first at WBAI in 1962–63, when I was music director. I was thrown out during one of those periodic palace revolutions. My successor was John Corigliano. In 1968, Frank Millspaugh, then the station manager, asked me to come back. He was specifically interested in the idea of doing live music. He wanted me to connect WBAI with the Hunter series. I told him that I didn’t think it was going to happen. But we agreed about the value of doing live music at WBAI. The Free Music Store could provide a live music venue for WBAI and more importantly, would establish that WBAI was the place where you heard live music or live-tape music that was created or recorded specifically for the station — and not commercial music. WBAI was interested in the quality of broadcast and recorded sound. Lou Schweitzer [businessman and philanthropist who owned WBAI as a private station in the late 1950s] donated the broadcast license for the station to Pacifica; he was an audiophile, a free speech and hi-fi guy. So WBAI was already broadcasting in stereo. In short, we were involved early on in recording and broadcasting in stereo and doing live concerts.

We mixed Renaissance and contemporary music. The only thing we didn’t do a lot of was rock and roll, except some with political or folky quality, or artistic pretensions.

The Free Music Store started at Martinson Hall at the Public Theatre — which Joe Papp gave us to use. The president of the Public Theater was my wife’s cousin, a Martinson who ran the coffee company. He named the hall — then a rehearsal hall — Martinson Hall. It wasn’t being used much and he was anxious to start something there. The shows were immediately successful. There were no chairs, so everybody sat on the floor; and once again we had all kinds of music from the beginning. We had Tito Puento and Eddie Palmieri, Latin jazz musicians who nobody in the white community was listening to. Archie Shepp had a big success at the Free Music Store and he was sympathetic to the Free Music Store. We mixed Renaissance and contemporary music. Harpsichordist Igor Kipnis performed with people sitting on the floor, squatting under the harpsichord. The only thing we didn’t do a lot of was rock and roll, except some with political or folky quality, or artistic pretensions. There was already so much rock and roll with political overtones being played on WBAI and I wanted to widen things out by doing New Music. A lot of Bill Bolcom’s songs were performed and Joanie [Joan Morris, who sang his songs] used to perform very often. We also did some dance performances, which weren’t broadcast, although my own piece, [the musical component of] Peloponnesian War, was broadcast. We never paid anybody, but I gave people money for transportation. Everybody wanted to be in this series. The great thing was that the shows immediately went out on the air and that instant feedback brought in live audiences. We immediately had cache with younger people.

The name Free Music Store was stolen from the Diggers in California. They were giving things away and it was consciously taken from the Diggers. The music we presented existed outside of the commercial record companies and the establishment. In that way, we made a statement. We also offered a mix of musical cultures, which was very New York. We didn’t create this idea, but we brought it to people’s attention. The series impacted many people, including some unlikely types like Pierre Boulez. He was quite open about it being the inspiration for starting the Encounters series and rug concerts. He wanted to attract younger people and make music relevant. Boulez, incidentally, did a version of my piece Foxes and the Hedgehogs at Roundhouse in London with the BBC. And he also did a piece of mine with Quog Music Theater in the Encounters series.

The Ragtime Revival started at the Free Music Store. It was really Bill Bolcom and me, and it actually started in my living room. We found the original prints of rag scores and started to play them. Eventually Joshua Rifkin realized he was playing corrupt Ragtime and came to me. He was involved with Nonesuch. And then secret composers of ragtime, Jim Tenney for instance, came out of the woodwork and he performed at the Free Music Store. Bill composed and played his own new ragtimes, i.e. The Graceful Ghost Rag. The shows were always mixed bags with various performers. We discovered that Eubie Blake was alive and living in Brooklyn and he came down and played too. I told WBAI they could make a great income by putting this stuff out on record, but they refused, saying: “What do you mean, starting a capitalist recording company!” Later, when Gunther Schuller went to the New England Conservatory, he started a Ragtime ensemble. Having found the Red Back Book of original Scott Joplin Ragtime scores, he recorded the music for a label. His performance of Joplin’s opera Treemonisha came out of it, too. Joplin had published the score at his own expense and we did excerpts of it. Producers of The Sting liked his music [they wanted to use the Red Back Book arrangements as recorded by Schuller for Golden Crest], but never reached an agreement with the record company and so hired Marvin Hamlisch to do his own imitations, for which, ironically, he got an Academy Award.

The climax of the first year at the Public came when Gerry Schwartz, the trumpet player, offered to do all the Brandenburg Concertos together on the same night. He called his friends to play. People were climbing the walls to get in. It was the start of Gerry’s conducting career. But then, Joe Papp wanted to use the hall to put on his own shows, and so he told us that we had to leave. I got up during the Brandenburg concert and announced that we were looking for a new place. The New York Times was there, so it was in the papers the next day. Papp thought that I called the press on him, but this is something that I never would do. So I was on the outs with him for a while — and after a while, we made up. The Free Music Store moved into the Peace Church on West 4th Street. And then WBAI got its own place in a former church on East 62nd Street (the building was later replaced with a condo; WBAI sold it in one of its moments of financial crisis).

For a long time we had shows going every night. The neighbourhood we were in had lots of singles bars, so people turned up there. That took us up to 1972, when I finally left. By that time I had a cadre of people who were running the shows. The best-known person to come out of the production work was Ira Weitzman, who has worked with Andre Bishop at Playwright’s Horizons and the Lincoln Center Theater; he became a big music theatre person. After starting the series and doing the first four seasons, I left WBAI and the Free Music Store. With WBAI, I was fired once and came back. Second time, I just walked away. WBAI did great things externally, but were very contentious inside.

While the Hunter and Electric Circus series were both very nice, they didn’t last. The Free Music Store had a much longer run. It was a huge success in terms of impact and making a statement about the musical scene. While the classic uptown concerts run by Charles Wuorinen and Harvey Solberger were more lively than the New Music concerts we were used to, they were kind of stiff. Compared to what was going on in the visual Art world, and in video and dance, New Music was in a cocoon and not very relevant. I had a different concept of what music and, in particular, new music was about. Personally, I was going into music theatre with my Quog Music Theater ensemble and the new [American] Music-Theater Festival in Philadelphia, which I started with Marjorie Samoff in 1982 and which ran in its original form almost to the millennium.

I wanted to do these events in a different way. The overriding idea was to make concert life a relevant part of the culture and to explore all aspects of the culture as it exists. New York was of course a great place to do this. We wanted to get music — at least Classical music, as it was conceived of at the time — out of its little corner, out of its sheltered little place. We wanted to physicalize art and bring together different musical styles and explore them individually or through their interactions. We sought informality, including seating people on the floor. Immediate feedback was possible through the broadcast medium. The biggest fights at WBAI were always internal, with the political wing. It thought that the cultural side was irrelevant or icing on the cake, or that the cultural side should support the political side, not the reverse. We took contributions at the door, but didn’t charge for admission and we put the money into a separate account, so it would go to expenses rather than cover WBAI’s financial crises. I never could get them to start the record company, which could have made money from Ragtime music.

The Electric Ear Series at the Electric Circus

Thais Lathem lived in Brooklyn and so I may have first met her in the neighbourhood. At some point, she and I went into working at the Electric Circus. They offered us Monday nights — the dark, dark night. I have no recollection of how it came about. Tony Martin was involved from an early point. The big kick-off event we did was the John Cage and Marcel Duchamp chess piece, Reunion, in which the chess moves triggered all kinds of other events that were taking place simultaneously. It was an early version, a kind of circus event, which maybe interested Cage in doing more of this kind of work later on. It was a lot of fun. Tony had already done multimedia events in San Francisco, in rock clubs, and so he had the experience. Thais and I worked together for a while on the first year of the Electric Ear Series (1968–69) and then I left during the second. I was doing my own work, which was going into high gear. Thais and I worked together for a while and then went our own ways. Working together was always amicable.

Salzman’s Own Work During the Period and Quog Music Theater

One of my pieces was a modular work, which I took around the country and did residencies. I worked with students with whom I would put it together and do a big multi-hour extravaganza. It was called Feedback and my original collaborator (who provided the visuals) was Stan VanDerBeek. One of the big presentations was at Syracuse University, working with Louis Krasner (he had given the premiere of the Berg Violin Concerto in the 1930s and was now the head of the Friends and Enemies of [Modern] Music in Syracuse and a professor at the university there). A video version was made and shown on public TV. I also did a big version at Instituto Torquato di Tella in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where I spent a month teaching multi-media and music theatre at the invitation of Alberto Ginastera. (I was barely aware of what was happening politically in Argentina at the time, when the junta was taking over.) Students used letters that I wrote for them on letterhead in case they got stopped or picked up. Stan didn’t come down and instead I worked with Argentine artist Marta Minujin, a well-known artist who had been in New York. The Buenos Aires production also featured a local theatre group, Time of the Wolf [Tiempo Lobo], and a well-known (at that time) Argentine rock group named Almendra. There’s a photo of one of the versions of Feedback in an old issue of State Council of the Arts bulletin. Another work that I created at that time, The Nude Paper Sermon, was done for a Nonesuch record commission. I also did a multi-media exhibition, “Can Man Survive?” for the centenary of the American Museum of Natural History which was on display in the main lobby for two years and, as I like to think, was one of the things that sparked the modern environmental movement.

After I returned from Argentina and a big South American tour in 1969, a number of the people involved in these projects organized ourselves into a performance group, Quog Music Theater, which lasted 10–12 years. It was an ensemble to do New Music theatre and to develop ideas about it from a performance point of view. It included mostly singers, and some instrumentalists. Bill Schimmel, accordionist and composer, was involved. Also counter-tenor William Zukof of the Western Wind, drummer/percussionist Dave van Tieghem and many others. The group had a studio on 39th Street and 9th Avenue. It was in a building of studios, Space for Innovative Development, which was set up by Samuel Rubin, whose wife was the producer of the show No No Nanette. He was a philanthropist who also supported Leopold Stokowski’s American Symphony Orchestra. Quog did European and American tours and we also performed in our own studios, at The Kitchen in Soho, at La Mama, etc. etc. In addition to us, a number of other groups also had studios in the building, among them The Open Theater, Alwin Nikolais and Murray Louis, and various experimental jazz musicians. We held weekly improvisational events in which Phil Glass, Michael Sahl (with whom I wrote five or six music theatre pieces) and others participated. This was during a period of time when some other people, like Kirk Nurock, were doing similar things (Kirk’s group was called The Natural Sound Workshop). We also did public workshops, which used our ideas. Meredith Monk and the House did things like this, too.

Epilogue

Although The Space For Innovative Development closed in 1974, Quog Music Theater continued in operation until 1982. At that point, Salzman co-founded and served for a decade as artistic director of the American Music Theater Festival.

Social top