Interview with Maryanne Amacher, American Composer and Sound Artist

A unique sensitivity to sound

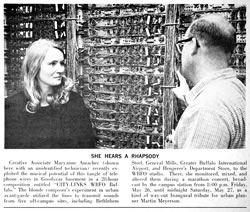

Maryanne Amacher (1938–2009) was a composer of site-specific installations, multimedia creations, and high volume, multilayered sound projection. Her work often addressed the perception of sound. Her sound installations were conceptualized as series of works, among them the multi-location City-Links and Music for Sound-Joined Rooms, the latter filling an entire home in Minnesota. Among her artistic collaborators were John Cage and Merce Cunningham. Amacher wrote in 1998 (Artist Statement, Foundation for Contemporary Arts): “I use the architectural features of a building to customize sound, visual, and spatial elements, creating multi-dimensional environment-oriented experiences, anticipating virtual immersion environments… The idea is to create an atmosphere that gives the drama of being inside a cinematic close-up, a form of ‘sonic theater’ in which architecture magnifies the sensorial presence of experience… The rooms themselves become speakers producing sound which is felt throughout the body as well as heard.”

The following interview was made in a restaurant in Kingston NY on 15 December 2008.

[Bob Gluck] Maryanne, where did you start out?

[Maryanne Amacher] I would work in different studios. I had been an Associate at the Center For Performing and Creative Arts at [SUNY] Buffalo, the same year as Cornelius Cardew. I had not been away from there for very long.

The same year when David Rosenboom was there?

I was there before he was. Nick Castiglione, Cornelius Cardew and an Argentinean composer. Bob Martin, the cellist at Bard, was one of the performers. They would bring in musicians and then maybe three or four composers. But before going there I had worked at the University of Illinois in the electronic music studio. I worked by myself, although I took courses in Acoustics with [Lejaren] Hiller. I just had this European way I guess, of calling up, seeing if I could work in a studio and then working there.

You were an undergrad then?

No.

So what were you doing working at the University of Illinois?

I went there as an assistant to a mathematician, John Myhill. He was very interested in music and he worked with Hiller. I took one year of courses because I was very interested in programming. Since I had always gone to school in the East, I never was at a school where I could have a studio space, until I started going to these studios. There, I [had] direct acoustic experience. Also at Illinois I could go in and play all those percussion instruments. It was fantastic. I worked there for a year and that’s how I began my music. Before that I didn’t do my own music.

Had you grown up as a musician?

I was a pianist! But I always imagined a certain kind of music and I would study all these scores and I’d try to create it. And I didn’t know how to do it until I was able to work at Illinois.

Had you been aware that there was such a thing that existed as electronic music and studios?

Oh, yeah, of course.

How did you know about that?

I was precocious as an undergraduate, at the University of Pennsylvania. Underneath me was the Morris School of Engineering. I had a job actually in the Programming Department, Mechanical Languages. I used to go downstairs all the time and get all the books on electronic music, which was great fun. And I had gone to Columbia[-Princeton], because I was also around these brilliant mathematicians who were great fans of music, so I learned a lot. We’d talk about this stuff all the time. These were amazing people, so I always valued that very much, that part of my life. In fact, one of them quit MIT because of the war stuff, and he was at RPI [Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute] for years. This was Robert McNaughton, a very eminent professor, now emeritus.

Back then it was very difficult to work on any computer system without having a foot in the military.

I guess certain places were worse than others. So then I came to Buffalo. I didn’t really work in a studio there; I did productions and other kinds of my work.

1967-1971: Boston to New York, Mort, Serge…

Had you started doing any of the installations?

I did that when I went to Buffalo. And then I wanted to develop this music. I met Moog before, so I called him up to see if I could work in his studio [in Trumansburg, New York]. I got on a plane from Buffalo to Trumansburg. I was creating this new work, not with any formality.

How did you get to NYU?

How I got to NYU is to me what’s so impressive and beautiful: Mort opened this place to people. It’s very much like the San Francisco [Tape Music Center] situation. I was asked to write a review on David Bernstein’s book 1[1. The San Francisco Tape Music Center: 1960s Counterculture and the Avant-Garde, University of California Press (2008).] this year. It was wonderful to read about it. All the time [while reading] I was thinking: “Mort continued this approach; it was beautiful.” I never counted any bureaucracy. Where did Charlemagne [Palestine] come from, where did Rhys [Chatham] come from, where did I come from!? No one approved us, except Mort.

However Mort wanted to welcome people.

Yes. It was so open and so beautiful.

Was there a particular thing he wanted you to do in exchange for your time there?

Nothing.

No cleaning, no editing, no…?

No. Serge [Tcherepnin] did all that. But Serge wanted to because he wanted to build electronics, so that was just fine.

Had you met Serge before that?

No, I met him there.

Was he already there before you arrived or did you get there first?

I don’t remember. I think he probably was there. He hadn’t been there very long.

Were you actually living in the studio? Did you have an apartment?

Serge and I lived together in his father’s place on 73rd Street. I got myself a little private room in that building, which was where they used to have the projector. It was like a coffin, a totally black room. That was biggest from here to here [shows very small dimensions].

Mort referred to it as a Porter’s Closet or a Porter’s Room.

Oh, did he?! [Laughs] I was trying to remember the other day whether it was painted black or whether I painted it black.

How did you end up with it? There was not a lot of space there and there were a number of people coming through.

Who else would want it except me! I wanted this little intense little space.

What did you like about it?

For one thing, I enjoyed being in a private space. But I really wanted to be in a black space to experience certain visual phenomena.

Did it work?

Yeah. You know when you have your eyes shut for a long time and you wake up and there’s not a lot of light around, it’s very different. I was at that time doing music that was very much at the threshold of perception. So I was interested in making those experiments. Also, I could play sound in there.

Was it relatively soundproof?

Yes.

What did you have in that room? Did you have a tape recorder, any equipment?

Maybe loudspeakers and a mixer. I must have had a tape recorder if I was playing music.

Were you getting any of your music heard in New York?

No. I was doing my various explorations. Before, when I was associated with the Buffalo group, my first composition was played actually at the Carnegie Recital Hall, which was actually a work for the musicians moving their sound around the room. The score was all notated for that, very carefully done. It was very interesting to do. But unfortunately, those space boxes the person made didn’t work. So you can believe that all those years I never heard the spatialization of that piece. I just played it on four speakers, spread out.

This is the kind of story that I’ve heard from a number of other people about equipment not working and not allowing their work to be realized as they planned.

It was so different in those days. It’s just amazing. So different. I was into various psychoacoustic patterns. I was first detecting them, so I was always trying to stabilize these beat patterns, before the octave and the fifth, when its not beating anymore, and you just have these wave shapes. It used to drive me mad. Oh, Queens [College] was a whole other studio. When I worked there, the studio was 98 degrees; that’s when I stopped. You were locked in for the weekend. Serge used to bring me food. I guess I worked at both the NYU and Queens College studios at the same time because I wanted certain things that were at Queens.

Did you do any work with Serge’s own oscillators — that were more stable?

He didn’t have them at that time. That was later.

Do you have a splicing career?

Oh, yes.

Going back to Illinois?

Yes, that was the first time I ever did it.

Did you leave with Serge for California?

No. Rhys and I decided we didn’t want to go.

Why not?

I don’t really know. I didn’t really want to go.

One thing that I’ve talked about with people is how some things they began to develop in New York really developed in a bigger way when they got to CalArts.

Yes.

And some decided they didn’t want to go.

Well, Rhys started the [music programme at The] Kitchen. 2[2. For more on the opening of The Kitchen and the New York scene in the early 1970s, see Bob Gluck’s Interview with Rhys Chatham in the next issue of eContact!]

Before The Kitchen, were you working in the studio in the Film School basement that Michael [Czajkowski] set up?

I was never in a basement [studio at NYU].

After NYU closed Bleecker Street…

I never went to the other place.

Did you overlap with Eliane Radigue or did she come after you?

I always knew her at Mills.

So you never knew her at NYU. What about Bea Witkin?

She was there.

Apparently. There isn’t really good information about it. There is an archive with her papers at Wesleyan University that includes tapes with notes marked “1971” and an archivist found information that some of them were done with a Buchla, labeled “1972”. Mort remembers her name, but isn’t sure. Charlemagne remembers her, but can’t place more info.

I don’t think she was there very much. One thing I remember is that she was good friends with a famous comedian.

What else do you remember about the NYU studio?

It was a fabulous place. We could talk. Everyone worked — I used to work at night. Rhys would come in — he would make me really mad — he was just a teenager, but he would come in first thing with his suit on, 7:00 in the morning. And then I’d have to get out of the studio. But Charlemagne and others of us worked all night. Charlemagne would run out at five o’clock (in the morning) and get fresh croissants at the bakery. They were always talking about different music, ideas we had, and other things. It was really wonderful.

Some have said: “Well, I showed up for my time and when I was done, the next person was waiting to come, so I got to say goodbye but that was it.” Some had little contact with others. You seem to have had a lot of contact.

Oh, a tremendous amount of contact. Ingram [Marshall] too.

What do you remember about any organized system of sign-ups for time, or did you just come and go when you wanted?

Oh, I think we signed up. It was just an open place that worked out just beautifully. People would just come there. Where did Ingram come from? Where did Charlemagne come from?

Kind of magical.

And then people were able to have this communication in an academic environment, to be that open, it was just beautiful. And what they were thinking of.

Did you go to any of the various performances before The Kitchen started?

No, because there weren’t any.

Before The Kitchen era were people getting their work heard?

Not much. There wasn’t much New Music until Rhys started The Kitchen.

What about the Free Music Store at WBAI? That was ’68 that it starts. Charlemagne did something there.

I remember a gal composer at ACA, too, who had a radio programme and she used to do our stuff on it at that time. The name escapes me.

Did you ever go to the Electric Circus?

Yes. I even went to the one in Toronto.

What do you remember about it, anything really stand out?

I didn’t go to the ones you were just talking about. I went to [performances]. When Marshall McLuhan would come, play chess with John Cage, like that. You know, it was the same stuff, with psychedelic lights. What am I supposed to say? It’s Great Art? [Everyone laughs] No, it was a thing of the time.

Did you go to the Circus any of the evenings? Were you a regular at the Circus when there weren’t special performances?

No.

And Toronto?

It just was a new designed space and Buchla was there. Buchla invited me. Mort went, [it was] like a party, so we went up there.

1971: The Kitchen Opens; Early Sound Explorations

When The Kitchen opened, it overlapped — same people, same time. Did you do anything at The Kitchen?

Yes.

What did you do there?

I did a concept piece. They didn’t have any money. I was in Boston at the sound studio, Pretty Miss Elba. I was able to work there. A real mixing studio, a real pop studio. So I said: “Ok, Rhys, I’ll send you this piece from Boston.” So I wrote this text and people came to the concert. Rhys did some things; I don’t know what he did. Gave this text, but there was no audible music. It was a psychic thing.

How did people respond to that?

Jon Gibson said he heard the music; I don’t know. They didn’t have any money; I wasn’t going to go. I didn’t have any money either. I wasn’t going to go from Boston to New York. I don’t even know if you got the door at that time.

It was an interesting time. [One of the things that I think about is] how it connects to the San Francisco Tape Center, because that was such a great spirit, how they did that.

Did you see that as a continuation, a transformation?

I just think it’s interesting when you get a community of people. Artists now are interested in this again. When there’s a community of people. There was a lot of this happening then. I used to work with a group from Yale, Pulsa, but they all quit art. One’s a super real estate magnet in San Francisco. Another had taught for years at the Mari Ishi School, a painter. There was a group of them, about eight, and they did these large media installations.

One was in Central Park.

Yes, and the Museum of Modern Art. And Philadelphia, that was a beautiful one. But it was the idea of these kinds of things, of people working together. Not necessarily collaborating — they worked as a group — we didn’t do that [at NYU].

Why didn’t you?

These were all early explorations — for me, for Charlemagne, for Rhys, for Ingram. Ingram hadn’t composed much at that point.

What were some of the issues that were most in the air, that you were most talking about with this group?

It depended on what we were listening to, what we were responding to in our music. Charlemagne and I were very much into beats and harmonics. So we talked a lot about that.

Were you listening to a lot of music from elsewhere?

I was listening to world music, music from Tibet, New Guinea, Japan and Chad.

How was some of that affecting your thinking about beats and acoustic and perceptual phenomenon? Were you making connections between what you were hearing and doing musically?

Well, I had direct experience of that with Tibetan music. I was staying at a friend’s apartment on the Upper West Side and I was playing this wonderful Tibetan record where the pulse is completely stable. And I wanted to adapt that in my own music because I could never get the oscillators with pitch — I could never get them steady. So for those reasons I was playing it in this apartment and eventually this woman comes up from five floors below. She didn’t hear sound, she just got this pulse and it freaked her out. She didn’t know where it was coming from. She followed it, the steadiness. There are very powerful perceptual things in sound if you listen. It’s a stability of an entity, of a being. You don’t hear the gong or the drums or what else was playing. Like good pianists or good musicians do that in a different way.

[Recently, I listened to a piano recording and it upset me]. To be this sensitive — I woke up the next morning and I had various revelations about my new work as a result of this experience.

Like what?

I’m not that scientific, but I’m very objective about my music. I work with certain psychoacoustic things. It’s usually pretty straightforward and then I go in and discover them. But I don’t think necessarily about these kinds of things why, why we as human beings would be so — although I know this, but I forget about it — how we as human beings can be so sensitive that I can wake up next morning [and still be affected by the piano recording]. I had a conversation with someone who has a very beautiful voice. [Her sound had] curves and shapes, but the sound of that piano recording was like a big Mac truck. [This is how sensitive I am to sound]. This pianist, he might have been a good pianist at one time.

It’s funny you say that because I think, with my students, of the opposite — how people can be so utterly unaware of the sonic space around them, how hard it is to get people to pay any attention, they are so trained to just tune everything out. Listening in a very functional way.

But they know; they get it when it happens.

It could well be.

They get it. The student concert I went to. He’s got that capacity to communicate. He was mostly doing music, but he had invented things. He has the capacity to speak to you, not to be out, not touching sound or something. I know audiences get these things.

You think they connect the fact that they are experiencing something?

If they write their responses about it, if people write about it, and talk in the audience, which I have had happen at festivals, [then they clearly do].

What did you do after NYU? Did you have a studio to work in after that?

After NYU, I tried to get as much stuff as I needed to work with myself. Those big oscillators and stuff. Then I went to MIT. I became a Fellow at the Center For Advanced Visual Studies, where I could set up my own studio.

Social top