“Mockingbird”

Abstracted confessions through political music

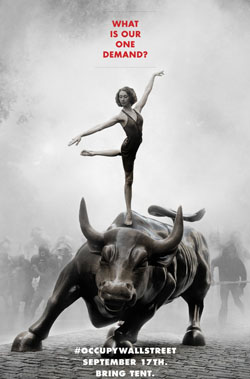

Socio-political art, like politics, has long played an important role in many cultures and can be a provocative topic to address. The creation and political appropriation of visual art and music during times of war and revolution can be found in examples ranging from sculptures and symphonies celebrating heightened wartime nationalism to paintings and commercial music protesting injustice. Politics and music can come together on several levels when a tumultuous socio-political event or significant level of protest and activism occurs, resulting in inspired artistic staging and creation. This was evident in the Occupy Wall Street (OWS) movement, with the related protest chanting, singing and drumming heard at the events, as well as the songs and art that it subsequently inspired. OWS was a stand against inequality and corruption, and became a battle that pitted the many against the few within a system of control. A message was there in the movement, but it was lost or distorted in the corporate media’s translation. The message can be found in the narrative formed from the events and the actions of all involved. Perspectives on politics in music and some of the conceptual and compositional possibilities of an approach I have termed “musique documentaire” (initially labeled “abstracted aural documentary”) are illustrated below through a discussion around the creation of Mockingbird (2015), my acousmatic portrait of the event.

Political Vibrations

The very notion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political position.

—George Orwell

An interesting question, frequently proposed and discussed, is whether art, including music, should be political and whether it has any place at all in being so. This line of thinking is precisely what George Orwell is addressing in the above quote. Throughout history, many compositions have been written as political statements or have been associated with politically charged movements. One frequently cited example is Ludwig van Beethoven’s Third Symphony, the Eroica (1804). Originally dedicated to Napoleon Bonaparte as a hero, Beethoven aggressively removed the dedication when Napoleon proclaimed himself Emperor of France. Several of Giuseppe Verdi’s works became anthemic, were sung by the public during the revolution and began to symbolize the unification of Italy. Dmitri Shostakovich and Sergei Prokofiev created works under immense political pressure and, although some of their works are specifically Soviet propaganda and praise Stalin, the composers’ true politics came across in others. Starting in the early 1950s, many of Luigi Nono’s works lauded communism while denouncing fascism; they were also anti-capitalist, which was an important contributing factor to the initial resistance in America to embrace his works (Sallis 2011). Meanwhile, from an American perspective, Steve Reich has produced several politically charged pieces, including Come Out (1966), Different Trains (1988) and WTC 9/11 (2011). Frederic Rzweski is well known for political pieces such as Coming Together (1971) and its companion piece Attica (1972), but The People United Will Never Be Defeated! (1975) for solo piano is of particular interest here. The work is a series of 36 variations on the Sergio Ortega song El pueblo unido jamás será vencido, with a text written by the Chilean folk group Quilapayún in 1973; the song immediately became a traditional international protest chant, used even decades later as a rallying cry at OWS protests.

Their candy-box Beethoven is not our Beethoven.

—Friedrich Nietzsche

Music can be made political in ways unforeseen by the creator, such as what happened in Germany with the entartete Kunst (degenerate art) and entartete Musik (degenerate music) exhibits of banned modern art that premiered in Munich with the opening of the Haus der Kunst in 1937 and subsequently toured. While the intention was to ridicule and discourage interest in modernism and rid the country of “degeneracy”, the act of banning or censoring these works stirred an unexpected curiosity among the public and attracted millions of visitors. There were the anticipated negative reactions, but there was also a certain level of cachet owing to the scandalous nature of the exhibit and an increased interest in the very art movement that provoked such intense Nazi opposition. Meanwhile, the National Socialists heavily promoted the music of Beethoven through regular radio programming and incorporated it into Nazi propaganda films and feature movies. Proudly considered, along with Richard Wagner and Anton Bruckner, a representative of quality German music, Beethoven’s symphonies were performed at ceremonies and festivities during the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. This was not all that unusual as German politicians had been exploiting Beethoven for their own gain for decades prior. Otto von Bismarck declared: “If I heard this music often, I would always be very brave” (Dennis 1996, 32). When World War I broke out, the Berlin Philharmonic made the programming of Beethoven a priority and it was said that by the winter of 1915 his music could be heard performed in Berlin up to three times daily (Dennis 1996).

This political appropriation of Beethoven’s music is a constant: as a more recent example, in 1989 the Berlin Philharmonic performed a concert of Beethoven’s First Piano Concerto and Seventh Symphony for the former East Germans shortly after the reunification of Germany and fall of the Berlin Wall. Additional celebrations included a performance of the Egmont Overture and the Fourth Symphony led by Yehudi Menuhin, while later in the year Leonard Bernstein conducted a pair of concerts of the Ninth Symphony (Dennis 1996).

The way to carry out good propaganda is never to appear to be carrying it out at all.

—Richard Crossman

In one unusual case, the political direction of art music in a foreign nation was manipulated by a government body, as the Darmstadt Summer Courses for new music in Germany was “a bold initiative of the American military government” (Saunders 2000, 23). A secret Cold War programme of tremendous resources was established and underwritten by the US government to promote American values (mainly capitalism) and disseminate anti-communist and anti-Marxist propaganda, and to re-educate Germans while advocating a modernist direction in music that the Russians and National Socialists had considered degenerate (Saunders 2000). The US Military Government saw the cultural re-education, legally known as Entnazifizierung (denazification), “as a top priority” (Beal 2006). 1[1. A military government, as referred to by Beal, is a government that is legally or illegally administrated by military forces domestically or in foreign land. In this situation it was officially known as the United States Office of Military Government in Germany (OMGUS) during the occupation. “The State Department’s exchange programs were all part of the plan to set German culture back on its feet and to guide the progress as deemed appropriate by the victors” (Beal 2006, 18).] This was partially achieved through the establishment and covert financing of the Congress of Cultural Freedom (CCF) by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). While its existence was initially denied, this propaganda juggernaut was established in thirty-five countries, published over twenty magazines, owned a news service, created TV and radio documentaries, encouraged academic writing on abstract expressionism and experimental American music, opened venues for new music, held conferences, experimental festivals and art exhibitions, and awarded numerous prizes and commissions for musicians and artists. As Frances Stonor Saunders elaborates: “Whether they liked it or not, whether they knew it or not, there were few writers, poets, artists, historians, scientists, or critics in postwar Europe whose names were not in some way linked to this covert enterprise” (Saunders 2000). This account is downplayed by Amy Beal, however: she acknowledges the “lavish policy” of cultural funding by US agencies, but sees it as merely an extension of the rebuilding of a ruined city in occupied Germany (Beal 2006). The CCF ran from 1950 to 1967, with CIA agent Michael Josselson in charge of the overall operation, Melvin Lasky handling propaganda intended to direct German intelligentsia towards the American way, and General Secretary Nicolas Nabokov managing the music programme (Wilford 2008). With the promotion of formerly condemned European music and regular funding for US composers to attend and instruct, Darmstadt was to become a hub of new music and gathering place for musicians and composers of formerly fascist-occupied Europe. Ironically, pro-communist Nono would become a mainstay at the Courses (Iddon 2013).

Perhaps more conspicuous and accessible than in art music, protest content can be found in various genres of popular music, especially folk. Although very different stylistically and functionally, art music is nevertheless complementary with popular music when embedded with socio-political messages and thus both may become a catalyst for change. Some politically leaning artists include the following: folk singer-songwriters Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell and Pete Seeger; pop/rock artists John Lennon and Bruce Springsteen; reggae artist Bob Marley; punk band the Sex Pistols; jazz-rock fusion artist Frank Zappa; hip-hop artists Killer Mike, N.W.A., Public Enemy and Tupac; and hard rock and metal acts Megadeth, Rage Against the Machine, System of a Down and Tool. Somewhat related to popular political and protest music is the rebellious, thought-challenging work of comedians Lenny Bruce and Bill Hicks. In fact, Hicks, a former musician, often worked music into his comedy performances and album releases, while Tool had him open concerts for them at Lollapalooza, sampled his work in their songs and dedicated an album to him. Tool singer Maynard James Keenan stated: “The music is a catalyst for the ideas, his ideas were what really resonated with us. I think that is what he really liked about us as well — that we were resonating similar concepts” (Langer 1997).

Musique documentaire (The Way I Hear It… )

Unsatisfied in my search for existing terminology that effectively captured the essence of acousmatic work containing a musically treated documentary narrative, the need for a new descriptor surfaced. Effective terminology was a necessity due to the Coast X Coast electroacoustic lecture/recital series I co-founded with James O’Callaghan in collaboration with the Canadian Music Centre (Garbet and O’Callaghan 2014). Looking upon myriad related but differing æsthetics within the umbrella of electroacoustic music and sonic art, I began to look to other artists working with similar ideas, and this path immediately led to radio art, including radio documentaries and radiophonic plays.

It should come as no surprise that state-funded radio stations like the BBC and CBC would be at the forefront of experimentation in this medium during the 1950s through the 1980s, considering the budgets, equipment and expertise available to them, in addition to the prevailing Zeitgeist. Glenn Gould’s method of “contrapuntal radio” is perhaps best exemplified in the experimental radio documentary The Idea of North (1967), produced for the CBC (Gould 2000). Another example of radio documentary produced at the CBC was the long-running dramatic radio news show, Sunday Morning. One particular standout episode from 1983 featured interviews with a child in Grenada done by Robin Benger. CBC engineers back in Canada enhanced the dramaturgy with recordings, such as the slowing down of a helicopter’s rotors, as well as other studio manipulations. Of particular poietic interest here is that Benger was unaware of the additions that were made until after the fact (Benger 2015). Also working in radio, Gregory Whitehead is a prominent sound artist who has worked extensively with radio documentaries and radio dramas, including significant work for the BBC.

Outside of radio, some composers working in the field of electroacoustic music and sonic art have explored politically oriented narratives or a documentary aesthetic. Yves Daoust’s Mi bémol (1990) contains protest chanting, news clips and sounds from the Oka Crisis in Québec (Daoust 1998). Chris DeLaurenti does work in phonography, which he describes as “protest symphonies”, with political subject matter that has incorporated sound material from events like the Seattle WTO protest and the Ferguson standoff. Trevor Wishart’s Red Bird (1977) is an example of pure sonic art. Both peaceful and violent, it most certainly presents a simulated political narrative and is appropriately subtitled A Political Prisoner’s Dream (Wishart 2000). John Young's Ricordiamo Forlì (2006) contains a strong narrative that presents how his parents met along with abundant archival content and recollections from World War II within a musical framework. It has been hesitantly described by one critic as “experimental radio art” and by Young as a “hybrid documentary, radiophonic, electroacoustic work” (Young 2007); these varied descriptions of Young’s piece are examples of a need for consistent terminology. This short list of electroacoustic artists using materials having some degree of political content shows focuses on how the diverse techniques and approaches they are working with can have shared similarities and commonalities, yet only Ricordiamo Forlì is what I would consider an earlier work that can be labelled an “abstracted aural documentary,” the term I originally proposed, or musique documentaire. 2[2. Since first presenting these ideas at TIES 2015, I have found that “musique documentaire” is a more effective term than “abstracted aural documentary” and will therefore use this term from this point forward. Other terminology involving the words “electroacoustic”, “acousmatic”, and “musical” were all considered alongside “documentary” but were rejected for this specific style of composition for reasons that will be addressed in future writings. In addition to the many descriptions affixed to Young’s Ricordiamo Forlì and the varied body of radio art, one of the JTTP 2015 winners, Guillaume Campion, described his work as “acousmatic documentary”.] The descriptor and compositional æsthetic is certainly also influenced by seminal works such as Red Bird.

With these artists and diverse works in mind, the concept of musique documentaire was conceived to describe a work that is inspired by the radio documentary paradigm and combines documentary film practices with the transformational language of electroacoustic music. There is significant variety in what defines a documentary and Bill Nichols provides, in his modes of documentary, a very thorough and pragmatic list covering traditional narration to the avant-garde (Nichols 2010). Musique documentaire would naturally contain a non-fictional narrative and, as is the case with soundscape composition, would tend to have a form that emerges out of the primary sound materials (Westerkamp 2002). Along with the abundant accessible documentary cinematic techniques, several literary devices are available for use in the compositional process. An intermingling of various styles is how I hear it, a creative musical treatment mixing documentary and phonography, but leaning more towards the musical side. The end result is a mix or continuum between acousmatic music and aural documentary.

In Mockingbird, all the transformed sounds are abstracted from the source material and are a combination of aural and mimetic discourse. Soundscape works that include abstracted sounds may have the primary sound material transformed to the point where the source cannot be easily recognized, but a subconscious or conceptual connection remains, one that reinforces the theme of the work. This link is greatly enhanced when the processed sounds are organized in close proximity to the original material (Audio 1). However, a work that leans heavily on abstracted material and sits further along the continuum towards total abstraction will have a diminished relation to any real-world context. Although there can be similarities, recognisability of the source is but one element of many that distinguishes soundscape composition from this sometimes related style of work (Truax 2002). Regardless as to whether it is abstracted or abstract, there is also the aspect of how it is interpreted by the listener, who could hear it in an entirely different manner than how the composer organized it. There are two perceptual sides to this, with unpredictable associations. For example, the listener could listen to a work as abstract and unrelated to the source material, whereas the composer understands it as abstracted. There is therefore a potential for a wide continuum of interpretations and associations of any given sound transformation (Emmerson 1986).

Drumming As Language, As Message

Returning to the idea of protest music, while doing the field recordings at Occupy Vancouver, one of the more important but unexpected occurrences was a sonic wall of drumming. The coordinated rally was held at the Vancouver Art Gallery and three complete drum kits were set up on the east side of the building. In the spirit of community, anyone was welcome to participate and take a turn on a kit. Drumming became increasingly prominent as a backdrop to the activity of people talking over megaphones and contributed to the social interaction amongst the crowd; sporadic drumming could be heard all day throughout the vicinity. The drum has a history of being used for collective identity, communication and enhanced emotional energy, albeit for different intended results, ranging from peaceful resistance and protest to violent conflict and military functions. There is an extensive history of drumming, usually with portable or hand percussion, ironically connected to both battlefield and protests. One primary difference is that military drumming is highly regimented, whereas protest drumming tends to be more spontaneous with a looser feel. Being cross-cultural and multi-generational, drumming can often serve as a unifying force in a large gathering and speak to people of many walks of life. Drumming unexpectedly became a feature in my recordings: by walking amongst the kits, different perspectives and balances were achieved, and most of the interviews I recorded have a background layer of drumming and megaphone-amplified voices reflecting off the surrounding buildings.

As with field recording in general, the recording of the protest, drumming, interviews and protest chants is an act of documentation and preservation. With the advent of recording devices like gramophones and phonograph cylinders, primitive and challenging to use, early folk song collectors such as Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály worked hard to preserve authentic music. Advances in sound quality and portability vastly expanded the options for recording in a variety of circumstances. In the early 1970s, the World Soundscape Project at Simon Fraser University did invaluable work documenting multiple European and Canadian acoustic environments using a Nagra reel-to-reel tape recorder and encouraging people to listen thoughtfully. Without over a century of audio documentation in a multitude of projects, several of the captured sound worlds would have been lost in time. It should be stated that any act of documentation contains limitations and is inherently selective, and is therefore an act of political agency. This harkens back to the diversity of possible approaches explained in Nichols’ modes of documentary, personal viewpoints, and the continuum between the truth and a truth. 3[3. The wide variety of the six modes of documentary include nature narration, purely observational, participation by the filmmaker, an emotionally engaged performative role, an artistic approach and a totally uncontrolled approach.]

The onset of the protest section in Mockingbird features Occupy Vancouver material made up of the drum kit field recordings layered and mixed with interview recordings. In the spirit of drum circles, the drumming was rotated in multiple streams within an octophonic space and layered in ways that is not realistic but enhances the energy and vibe. This circular drumming effect was created with multiple streams of the beats sculpted into a maelstrom of polyrhythm that at times becomes rhythmically ambiguous and more textural, essentially a sound mass (Audio 2). The embedded perspective (Truax 2002) — disembodied voices through a PA system or megaphone — inadvertently recorded in the background, along with the ambience of the gathering, contributed additional schizophonic intensity, a varying sense of nervousness or tension (Schafer 1977), and another voice to the polyphony.

… and Spatialization As Meaning

Another significant concept in this composition was the spatialization of key elements within an octophonic sound field. Arranged in a standard circle of stereo pairs, the voices of Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama are always assigned to the front two loudspeakers (left and right, respectively), talking to and at the audience. The audience faces forward towards the political voices in an Orwellian reference to telescreens and related obedient behaviour. News media and advertising elements are brought in to address the audience, similar to the politicians, primarily from the side speakers as well as the front. During the aforementioned layered cacophony of spatialized drumming, the voices are contained in the middle four speakers while encircled by the drums in all eight. Immersing the listening audience within the circle of drumming, protest, chanting and conflict was intended to result in a sensation of being there and within the protest. Another important percussive element is the use of transformed studio recordings of coins dropped onto various surfaces such as a wood table and bowls made of metal and glass (Fig. 1). This coin material introduces the audience to new, surreal, polyrhythmic sound worlds. There was a conscientious effort towards placing each primary element precisely within the sonic space, which would therefore become a factor in influencing the listener’s interpretation.

Emerging Into Form

The form of this piece arrived naturally during the compositional process, emerging out of the primary sound materials and the narrative. With documentary work, there often is a predetermined narrative; however, this can evolve during research, as events transpire and when working with the materials. The form emerging from the recordings is typical in radio documentaries as well as soundscape composition, but the acousmatic nature of a musique documentaire would encourage transformation for a musical direction. I have discussed experiences while recording the protest and now will describe how the composition’s narrative was influenced by the causal relationships that resulted in the OWS movement.

The composition that was to become Mockingbird was originally intended to be an exploration into the causation of war within a global framework of finances, natural resources and mass media. Coincidentally, during the planning phase Occupy Wall Street broke out (Fig. 2) and the recording of the activism in Vancouver began. Almost immediately, the nature and loyalties of the media were revealed as the machine ignored, underreported and downplayed the movement. Difficult for the public to get a feel for what was actually transpiring, it was through social media and the Internet that people were able to get an accurate picture of the number of people and groups involved, connect and get better informed. When, due to its size and spread, the movement could no longer be ignored, the ridicule by the media began: reporters were initially dismissive and even made fun of some of the participants, in particular the most eccentric OWS protesters (Chomsky 2013). What I found, however, when I went down and started talking with the people at Occupy Vancouver, were plenty of very intelligent and educated people who knew exactly why they were there (Fig. 3). There were people from all walks of life: union leaders, university professors, high school teachers, people from varied interest groups. In other words, an important part of the participants were exactly those people that the media seemed to systematically avoid representing or giving voice to. At that point it became clear that the story I began working with in this composition was shifting and the media was the story now.

And, my friends, in this story you have a history of this entire movement. First they ignore you. Then they ridicule you. And then they attack you and want to burn you. And then they build monuments to you.

—Nicholas Klein (emphasis mine)

This quote from Nicholas Klein, regularly misattributed to Gandhi, is actually from his trade union address in 1918 to the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America in Baltimore. Shockingly, almost a century later, the media appeared to be still methodically following the strategy Klein warned about:

- Ignore;

- Ridicule;

- Undermine.

How the mainstream media generally approached OWS is precisely how the news media material is presented and develops in Mockingbird. This was achieved in two sections of compiled media fragments — “ignore” in the first section, then “ridicule” and “undermine” together in the second — connected by sound materials taken from recordings of coins. The coins provide transitions between several varying sections: vintage capitalism propaganda moving to clips regarding deregulation; mortgage advertising clips leading into the stock market crash reports; between the sections showing the media’s change in approach; and finally functioning as an abrupt but crumbling pillar leading into the drumming and interview section. Aside from having a transitional role, the coins also serve as a symbol for the substantial importance of finances to the narrative as well as a metaphor for social change. The use of an everyday material, such as coins, as a sound object is familiar in acousmatic studio work, but in this context it has multiple layers of meaning. The coin transformations also offer a moment to pause, cleanse the palate and encourage different modes of listening in the various adjoining sections (Audio 3).

The ridicule and undermine material was straightforward, but how to present the media not reporting a story would prove to be problematic. I wanted to avoid the obvious option of silence, as I did not feel that would translate well in this situation. The solution was found by using clips of the media that ventured into calling out the mainstream’s deafening silence. To reinforce the point, these clips were treated with an array of glitchy white noise, test-tone signals and stuttering digital silence. The form is also based on material derived from recorded events or archived material. The timeline in the sidebar and following elaboration shows the correlated events leading to the OWS movement as well as indirectly related material from protests and news media manipulation that contributed to the narrative and form of Mockingbird.

Several of these events informed the shape of how the piece would formally unfold; however, for narrative effect, the order in the composition is not entirely chronological. The tone is set through audio of the Church Committee investigating the CIA’s operation to plant stories overseas, using foreign media, in order to manipulate public opinion. This was important because it highlights the biased behaviour of the media and establishes the level of external influence that is possible. In order to contextualize the events that led to the 2008 crash, I selected audio clips relating to several major government actions considered to be culpable: the abolishment of the Bretton Woods agreement by Richard Nixon, which meant was the US dollar was no longer backed by gold and global finances moved to a fiat currency; the Reaganomic stampede of deregulation in the 1980s; and the repeal of Glass-Steagall by US Congress, signed by Bill Clinton in 1999 and strongly backed by Alan Greenspan, Chairman of the Federal Reserve. The latter would prove to be particularly volatile, but collectively these policies allowed further deregulation of banking institutions and permitted their entrance into the insurance business.

The crash that occurred on 16 September 2008, which sent global financial markets into a tailspin, is attributed to gambling on the packaged subprime loans and credit default swaps that correlated with deregulation. Several worldwide stock markets and institutions closed temporarily, but the recession is generally thought to have lasted until 2012. The US government-led bailout of banks and other financial institutions occurred in 2008, with no oversight, restrictions or transparency, setting in motion a chain of events that would culminate in the Occupy Wall Street movement. The theory of “too big to fail” emerged, asserting certain banks were so vital to the system that they must be supported by the government when facing bankruptcy, while foreclosures on financially troubled homeowners were rampant and disregarded. Meanwhile, top banking executives received substantial bonus payouts from the bailout packages, many of who consulted on the bailout. These manœuverings by banking executives, secret dealings with government and social injustice were at the heart of OWS.

Audio from the police riots at the National Democratic Convention in 1968, where excessive police abuse, violent assaults and mass arrests of citizens occurred, was inserted within the section focusing on OWS clashes with police for a historical perspective. This flashback to 1968 Chicago is presented in Mockingbird in a similar fashion to how a documentary would temporarily cut to historical footage. The “entire world is watching” misquote by Obama is a literary example of allusion to the anti-war chant “the whole world is watching” from the flashback. Both are present in this section, with the misquote looped and functioning as a transition back to the OWS protests. The material bookending the Chicago flashback is entirely from OWS and the solidarity protests.

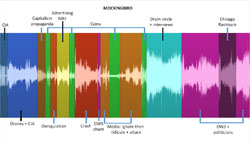

The flashback appears following an increasing density of material drawn from the initial compiled OWS marches and protest chants. After the flashback, there is a return to the marches but with an escalation and intensification using material related to conflict and police violence. Both sections of OWS marches contain a layer of irony, with sound bites from Obama and Clinton. The desired result was a juxtaposition of the politicians criticizing the suppression of free speech in the Middle East with the vastly underreported suppression of OWS protests happening in Canada and the United States, represented by the sounds of escalating police violence (the sounds include rubber bullets and exploding projectiles, reported to be flash grenades). Figure 4 is a graphic representation of the main sections of Mockingbird.

Conclusion and Reflection

From the scratching out of the dedication to Napoleon on Beethoven’s manuscript to the modern-day protest chant of “The People — United — Will Never Be Defeated!”, this is an overview of how politics in music led to Mockingbird as well as a brief explanation of how the term musique documentaire originated. Owing to graduate studies, new developments, discoveries and the accumulation process, Mockingbird is a composition I have been working on periodically in sections over the past few years, sculpting and expanding it in areas to be more thorough and comprehensive with how I observed the OWS story unfold and be contextualized by activists, media, politicians and scholars. With this composition I have attempted to answer some of the questions that the news media could — and would — not.

Bibliography

Beal, Amy C. New Music, New Allies: American experimental music in West Germany from zero hour to reunification. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

Benger, Robin. Personal Interview. 19 March 2015.

Buch, Esteban. Beethoven’s Ninth: A political history. Trans. Richard Miller. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Chomsky, Noam. Occupy: Reflections on class war, rebellion and solidarity. Second edition. Westfield NJ: Zuccotti Park Press, 2013, p. 69.

Dennis, David B. Beethoven in German Politics: 1870–1989. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

Daoust, Yves. “Mi bémol.” Musiques naïves. CD. Montréal: empreintes DIGITALes (IMED 9843), 1998.

Emmerson, Simon. “The Relation of Language to Materials.” In The Language of Electroacoustic Music. Edited by Simon Emmerson. New York: Harwood Academic, 1986, pp. 17–39.

Garbet, Brian and James O’Callaghan. “Coast X Coast: An Electroacoustic Lecture-Recital.” Prairie Sounds (Spring 2014), p. 8.

Gould, Glenn. “The Idea of North.” Solitude Trilogy. Toronto: CBC (B003H35OAS, 2000).

Iddon, Martin. New Music at Darmstadt: Nono, Stockhausen, Cage and Boulez. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Langer, Andy. “Another Dead Hero.” The Austin Chronicle 16/5 (May 1997). Available online at http://www.austinchronicle.com/issues/vol16/issue5/xtra.billhicks.side.html [Last accessed 3 April 2016]

Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

Orwell, George. “Why I Write.” Gangrel 4 (Summer 1946). Reprinted in Great Ideas: Why I write. London: Penguin UK, 2005.

Peddie, Ian. The Resisting Muse: Popular music and social protest. Burlington VT: Ashgate, 2006.

Saunders, Frances Stonor. The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the world of arts and letters. New York: The New Press, 2000.

Schafer, R. Murray. The Tuning of the World. Philadelphia PA: University of Philadelphia Press, 1977.

Truax, Barry. “Genres and Techniques of Soundscape Composition as Developed at Simon Fraser University.” Organised Sound 7/1 (April 2002) “Circumscribed Journeys through Soundscape Composition,” pp. 5–13.

Westerkamp, Hildegard. “Linking Soundscape Composition and Acoustic Ecology.” Organised Sound 7/1 (April 2002) “Circumscribed Journeys through Soundscape Composition,” pp. 51–56.

Wilford, Hugh. The Mighty Wurlitzer: How the CIA played America. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

Wishart, Trevor. “Red Bird: A Political Prisoner’s Dream.” Red Bird / Anticredos. New York: EMF Media (EMF 022), 2000.

Young, John. “Ricordiamo Forlì.” Lieu-temps. Montréal: empreintes DIGITALes (IMED 0787), 2007.

Social top