Between “Ludic Play” and “Performative Involvement”

Performance practice in gamified audiovisual multimedia artworks

Barbara Lüneburg and Marko Ciciliani both participated in TIES 2017 with their artistic research projects “TransCoding: From ‘highbrow’ art to participatory culture” and “GAPPP — Gamified Audiovisual Performance and Performance Practice,” respectively. The work of both artists is tightly connected to their research for GAPPP in which Ciciliani is lead artist and head of project and Lüneburg key researcher into performance practice. The following text reflects most recent findings in GAPPP.

Although computer games have become a popular research topic of interest for researchers in many different fields of the humanities and interface culture, in the domain of audiovisual composition and performance practice this topic has barely been covered. This is where the artistic research project GAPPP comes in. Our research starts out with the assumption that player interactions and game elements offer innovative æsthetic potential as well as new models of player and audience involvement that can be applied to the performance of live audiovisual works. We therefore commission, create and perform audiovisual compositions that incorporate game elements and principles, but still clearly belong to the world of contemporary (art) music. This creative process is part of the methodology we apply. We are interested in the effect the inclusion of game elements and principles has on creative and compositional decision-making, on audience perception and performance practice and, last but not least, on the artistic result. The study of these topics is assisted by data we have gathered from participant observation and audience questionnaires, interviews with composers, performers and audience focus groups, and — as is a principle of artistic research — through the artistic practice itself, that is composing and performing.

In my role as GAPPP’s key researcher for performance practice I am especially interested in the following questions: Do the game strategies offered by the composer enable the performer to shape the piece strategically in form and content? What kind of agency does the composer offer performers to further their involvement and render their actions meaningful? Do the performers’ decisions have a clear impact not only on the course of the game but also on the audience’s musical and visual experience of it? How do agencies afforded to the performer through software design and control devices for musical or visual interaction with the game system consequentially have influence on the players’ performative involvement and range of expression during a live performance? And last but not least: What are the findings with regard to the conditions under which “performative involvement” in gamified audiovisual multimedia artworks is furthered?

The Three Worlds of GAPPP

In GAPPP we move in at least three different worlds: The world of computer games, the world of contemporary multimedia (art) music, and the world of (Classical) performance practice. Each of these worlds has their own creative and observing agents, principles, goals, connotations, æsthetics and peer groups. This affects not only the works created, it also has an impact on the audience in their expectations and perception and it touches the work of the performer on several levels. For this paper I will approach the performance perspective from the angle of game theory. Three short GAPPP case studies are compared to assess the agencies offered to the performers and the resulting interaction and involvement. Christoph Ressi’s game_over_1.0.0, Marko Ciciliani’s Kilgore (parts 1–3 only) and Martina Menegon and Stefano D’Alessio’s Tonify all make clear reference to the world of computer games and work on the basis of interactive computer music systems (see Case Studies, below).

The terminology used here differentiates between two ontological statuses, that of “playing” (ludic play) and that of “performing” (musical play): “ludic play” is defined as actions taken with regard to the game system; “performing” or “musical play” is understood as actions that reach beyond and include musical or performative decisions and connotations that affect the overall “performance ecosystem that includes a performer, instrument and spectator, all as active participants that also exist within a society and draw upon cultural knowledge” (Gurevich 2017, 329).

Agencies in Computer Games and Their Meaning for the Concert Situation

Game researchers Michael Mateas and Andrew Stern differentiate between two forms of agency in computer games: “Local agency refers to the player’s ability to see the immediate reactions to her interaction, while global agency refers to the knowledge of longer-term consequences of a causal chain of events” (Mateas and Stern, cited in Calleja 2011, 56). Katie Salen and Eric Zimmermann, another pair of game researchers, state that “Meaningful play emerges from the interaction between players and the system of the game, as well as of the context in which the game is played” (Salen and Zimmermann 2004, 33). In the works of GAPPP, composers afford the performer agency on various levels (this will be addressed below through case studies of works by Christof Ressi, Marko Ciciliani and Martina Menegon / Stefano D’Alessio).

Salen and Zimmermann also argue that “The context of a game takes on the form of spaces, objects, narratives and behaviours” (Ibid.). What does this mean for the artistic works of GAPPP? When we play and simultaneously perform the audiovisual game-related works of GAPPP in a concert, we are concerned with a second layer of context: we look not only at a game with specific spaces, objects, narrations and behaviours being played by any player, but also at an artwork (shaped through the game principles that are applied) meant for and performed in the context of a live concert setting. A context that carries weight in the player experience and in the experience of the audience. This implies that the players or performers cannot only be concerned with their own ludic pleasure, but they also have musical and performative responsibilities to shape the experience for the audience. Salen and Zimmermann state that “[m]eaningful play occurs when the relationship between actions and outcomes in a game are both discernible and integrated into the larger context of the game” (Salen and Zimmermann 2004, 34). To me, as a performer who considers the audience to be at the core of my actions, this means that I would like to experience “meaning” not only in the game context but also in the context of the “performance ecosystem” — specifically in the context of a “performance ecosystem that includes a performer, instrument, and spectator, all as active participants” (Gurevich 2017) and in which meaning is experienced together. Therefore, in my opinion, the principle of “meaningful play” in works of GAPPP should apply to the performers and should in the best case have significance for the observing audience.

Conditions for “Performative Involvement”

The works of GAPPP are special in that they combine features of computer games with features of interactive audiovisual contemporary art. They propose a backdrop that makes audiovisual artworks (at least theoretically) more easily approachable to a young audience, since the composer, performer and audience will probably share some common cultural knowledge. They also provide a common structural and creative approach that is partially based on the ideas, mechanics or designs of computer games. In consequence, these works invite studies of their underlying interactive computer systems and design concepts, as well as the clearly defined agencies and objectives they offer to the player / performer, using methodologies of artistic research and sociology. Those agencies and objectives are sometimes more hidden, sometimes clearly recognizable for the audience, but in any case they influence the performer’s task of transferring meaning and expression to the audience in the concert situation. Therefore, they encourage not only investigation into the individual involvement of the performer and audience members in the works, but also the potentially shared comprehension.

Each of the works that have been investigated is based on what Robert Rowe calls “performance-driven” systems, meaning that there is a notated score that represents the music, the system reacts dynamically (often in a generative way) to the input and the work is based on the idea that the computer system follows “a player paradigm” by trying “to construct an artificial player, a musical presence with a personality and behavior of its own” (Rowe 1993). From my own perspective as a performer, the works that were particularly interesting were those that afforded other performers the option of “performative involvement”, that is an opportunity not only to “ludically” play the piece but also to musically and visually play and shape the concert situation. Such contexts thus granted the performer a meaningful creative agency and, as a consequence, a high level of responsibility, as well as involvement that can ideally be transmitted to and shared with the audience.

In order to fully appreciate such a performance-driven game system in the context of GAPPP, it would be necessary to define what could be meant by “meaningful” for a performer in a given performance situation that is defined by the interaction between player, work and spectator, between performer and digital music system, and by the artistic goal of the work and the greater context of the performance. In order to enable performative involvement, the designer of a work that is based on a generative, interactive music system needs to create meaningfulness with regard to:

- Technical skills. The work allows performers to gain or enhance their technical capabilities and thus heightens their sense of agency.

- Creative strategies and goals. Rules, strategies and objectives make sense, they are clearly recognizable and they grant agencies that allow performers to clearly influence the work musically, visually, strategically or content-wise.

- Musical objectives. The system and the work afford options to take musical decisions that make traceable sense and that are satisfying to performers and possibly offer unexpected but challenging contingencies.

- Sharing artistic experiences with the audience. The system and the work allow for performative decision-making and actions that let performers transmit the artistic experience on a social and artistic-communicative level in cognitive, sensor-motoric or emotional ways.

Three GAPPP case studies are used to determine whether it is possible to trace performative involvement and to reflect on what can generally be concluded with regard to performance practice in dynamic, interactive computer systems.

Case Studies 1–2

Christof Ressi — game_over_1.0.0 (2017)

for clarinet, sound module, sensors and computer game software

In Christof Ressi’s audiovisual work game_over_1.0.0, global and local agency of the performer are clearly designed. The clarinetist performs a shooter game that is situated in outer space and has clearly specified tasks. His avatar takes on the form of a little green spaceship that fires at hostile spaceships as they enter the field from the upper margin of the screen. A motion sensor fixed to the clarinet traces the performer’s movements horizontally and vertically. The movements are visually translated onto the screen as movements of his avatar through a virtual space — on the basis of the player’s instrumental movements (up down, left and right), the avatar can navigate through the entire screen space. From the perspective of Gordon Calleja’s involvement dimensions, the structures and goals of game_over_1.0.0 are distinguished by an emphasis on “kinæsthetic involvement”, i.e. performers substantially control the game through the movement of their instrument, and “ludic involvement”, whereby players make decisions in the pursuit of game-assigned goals (Calleja 2011, 4). However, it could be useful to expand Calleja’s proposal with what could be termed “performative involvement”, during which the performer undertakes decisions in the pursuit of a musical performance goal — as is typical for a concert situation.

During the performance of Ressi’s work, the musician improvises in parallel to a highly energetic electronic MIDI soundtrack (provided by the composer) that resembles the sound world of games from the 1990s such as Super Mario as well as the atmosphere of the arcades in which they were found. The performer adds to this musical environment by improvising on the clarinet while at the same time steering the game in order to complete his game-related tasks, such as shooting hostile spaceships (Video 1). Shortly before his performance of Ressi’s work, clarinetist Szilard Benes explained:

As a performer, as a player, I have various options to shape the music, the game itself, the roles I take on and various other things… I actually have room to manœuver and creative leeway with regard to what I can do and what I want to do. (Lüneburg 2017) 1[1. Ich als Performer, als Spieler, habe verschiedene Möglichkeiten, die Musik zu steuern, das Game an sich, die Rollen und verschiedenes Anderes… Ich habe wirklich einen [Gestaltungs-]Raum, was ich machen kann und was ich machen will.]

Musical accents (slaps) and short, high pitches on the clarinet are visually transformed into missiles that are shot at the enemies (Fig. 1). When shots hit their targets, the hostile spaceships explode; if they are misses, the spaceships’ return fire could hit the player’s avatar, depleting the available “lives”. Through his musical input, in combination with the movement of the instrument, the player can strategically manipulate the soundtrack and the visual scene, change the density and speed of the musical material, alter the pitch of the melody and harmonies, or increase the number of hostile spaceships. If, for example, the player’s avatar hits the walls of the space, the software transposes the action into a certain musical meaning for the piece, such as an increase in the overall tempo or density of the soundtrack; if the player stops moving, a different musical or visual action will be triggered. Ressi designed the game in a way that it grants the player meaningful local agency: the performer receives immediate musical or visual feedback to all their actions. Moreover, it offers the option for a performer’s “subversive play” — one of the practises Mary Flanagan describes in Critical Play: Radical game design (2009). “Subversive play” means that the instrumentalist performs “in a subversive fashion, in the context of a situation that is imbued with semiotic meanings, expectations and appropriate behaviour” (Oliva 2017, 2). Benes further clarifies:

There are various musical effects such as “slaps” or short tones [that trigger shots]; there are loud effects that I can use to drive the UFOs, the algorithms of the UFOs crazy so that they move very, very quickly, however — perhaps it might be best if I didn’t do that, because then I’ll simply die…. I can play this game in a way that it challenges me. (Lüneburg 2017) 2[2. Es gibt verschiedene musikalische Effekte wie zum Beispiel Slap-Tongue oder kurze Töne [die Schüsse auslösen], oder es gibt laute Effekte, womit ich die UFOs, die Algorithmen von den UFOs verrückt machen kann, so dass sie sich sehr sehr schnell bewegen, obwohl — das würde ich nicht so gerne machen, denn dann sterbe ich einfach…. Ich kann das Spiel so spielen, dass es mich herausfordert.]

For Benes, subversive play was often tightly connected with musical performance aspects, however, always intertwined in the play and the rules of the game:

The [computer-generated] music depends on how I play — I can change it through my playing. And with my musical ideas I can shape the game in such a way that it challenges me. Although that is not really easy, because to do it you really need to know all the rules. (Lüneburg 2017) 3[3. Die [computergenerierte] Musik ist davon abhängig, wie ich sie spiele, ich kann sie mit meinem Spiel ändern. Und mit meinen musikalischen Ideen kann ich das Game so spielen, das es mich herausfordert. Das ist dann wirklich nicht einfach, denn dann muss man natürlich alle Regeln wissen.]

Benes describes ludic and musical play in game_over_1.0 as a complex situation between music, play and game that requires a great amount of inner involvement. As he recounts in an interview with the author, it starts with his inner psychological attitude. To overcome boredom — after several rehearsals he already knows the piece quite well — he emphasizes the need for curiosity, in order to discover new options even after the tenth run-through, as well as to always listen carefully, not only to listen to the music, but also to hear and be aware of what is happening in the real (concert) space while playing the virtual game on screen. He sees beauty in always discovering new things, in changing little somethings in musical performance or in his strategic play within the game system. He talks about the necessity to always search and stay agile. If you do so, he says, there are millions of possibilities to make music or a play or a game and to change it again and again. He describes game_over_1.0 not only as a game, but as an interaction:

Well, one can really do funny things, and I find it good to have the power of decision… There is this symbiosis between the game and the player or performer, and all the time there is a God or a software programmer [the composer, Christoph Ressi] who can control everything or change it or actually do whatever he wants. He can oppress the player or he can just watch… [Y]ou have an almost unlimited range of possibilities to play. The only one who can limit it is Christoph. (Lüneburg 2017) 4[4. Also man kann man wirklich lustige Sachen machen und das finde ich gut, dass man die Entscheidung hat… Es gibt eine Symbiose zwischen dem Spiel und dem Spieler oder Performer, und die ganze Zeit gibt es einen Gott oder einen Programmierer [der Komponist, Christoph Ressi], der das steuern kann oder ändern oder was er will eigentlich. Er kann einen unterdrücken oder er kann einfach nur zuschauen.… [M]an wirklich einen unglaublich grenzlosen Spielraum. Der Einzige, der das begrenzen kann, ist Christof.]

Game theorist Oliva states:

In the cybertext [of games], players exert ergodic actions to traverse the text, and their ability to listen and react to musical cues structures the final musical output. The player, therefore, is not only involved cognitively in interpreting and understanding music, but actively reconfigures its sections through ergodic action. (Oliva 2017, 5)

In my opinion, the performative situation in which instrumentalists find themselves in when playing (ludic play) and performing (musical play) Ressi’s game_over_1.0. even exceeds what Oliva describes. Form, harmonic structure, tempo and melodic content, as well as certain aspects of the visuality and the storytelling are all manifest in the performance of the instrumentalist. The performer concurrently plays the game and performs it for his audience in the concert situation, i.e. he remains constantly aware of this twofold, simultaneous ontological state and creatively steers this process. The creative musical performance has high importance in the enfolding and in the perception of the musical work and the performer is given a high amount of agency in the total creative work. This requires enormous creative agility, clever ad hoc musical and strategic decision-making, and encourages the mental and cognitive involvement of the player / performer.

Interestingly, although our lab audience was relatively young and had affinities with game culture, the performance of game_over_1.0 was received controversially. There were those who were reminded of games of the 1990s such as Super Mario or Space Invader and could relate to the æsthetics, as well as those who were deeply drawn into the performance of the instrumentalist and imagined what it would mean to play the game themselves. The latter perspective was the case for a classically trained clarinetist who took part in Focus Group 2 of GAPPP:

Well, I personally would have been quite drawn in by the third one [Ressi]…. I was thinking that if I would play this and would have to figure out how these things work or which combination of tones is the reason for which reaction… I was thinking that you could spend hours with this and play and play and play and all the while practice and get better and better. That really affected me and drew me in. (Sackl-Sharif 2017) 5[5. Also ich persönlich wäre im dritten ziemlich aufgegangen [Ressi]…. Ich habe mir dann auch gedacht, wenn ich das dann spiele und selbst herausfinden muss, wie das Ganze funktioniert oder welche Tonkombination jetzt was verursachen… da habe ich mir gedacht, damit kann man durchaus auch Stunden verbringen und spielen und spielen und spielen und nebenher dann auch gleich üben und immer besser werden. Das hat schon auf mich einen ziemlichen Sog ausgewirkt.]

Still others experienced the piece as if they were watching it on YouTube, which they didn’t enjoy so much because instead of being a backseat player they would prefer to play it themselves. As explained by a sound designer and gamer who took part in Focus Group 2 of GAPPP:

It reminded me of this situation on YouTube, when I watch somebody playing a game. There are some who really like doing that but I am not one of them. When somebody is gaming, he does his thing and that’s it; I don’t put myself in his position or feel drawn in like he is. I need the directness, I need to be the player myself. (Sackl-Sharif 2017) 6[6. Mich hat das eher so erinnert, wie wenn ich jetzt auf YouTube jemanden zuschaue, der ein Spiel durchspielt. Also es gibt Leute, denen gefällt das voll und ich bin halt nicht so einer. Und wenn da jetzt jemand zockt, dann zockt er halt sein Ding herunter und fertig, aber ich fühle mich jetzt nicht so hineinversetzt wie er selbst. Also ich brauche das Direkte, dass ich der Spieler bin.]

The same clarinet player who felt drawn in by the piece, however, found the sonic world sometimes to be loud, aggressive and slightly unnerving:

After eight minutes I thought OK, now this is getting on my nerves, because it is really a bit too loud and… right then there were these really screechy sounds. (Sackl-Sharif 2017) 7[7. Nach acht Minuten habe ich mir gedacht, okay jetzt nervt es ein bisschen, weil es ist schon ein bisschen laut und… es waren dann halt eben so die richtig quietschenden Töne dabei.]

And there were those who enjoyed the spectacle and the sonic world, such as a composer taking part in Focus Group 2:

It is just so much fun to watch Ressi… I find it so cool and it looks like a lot of fun.… At first you have the normal Jump’n Run sound æsthetic in your head. But then these beautiful, elaborate sounds come in that somehow go so beautifully with the instrumental sounds. I really liked that. (Sackl-Sharif 2017.) 8[8. Ressi macht halt wahnsinnig Spaß zum Zuschauen… das finde ich dann voll cool und ich glaube, dass das voll Spaß macht…. man hat da erst so normale Jump’n Run-Soundästhetik im Kopf. Und es kommen aber so schöne ausgearbeitete Klänge dazu, die dann irgendwie mit dem Instrumentalen voll schön sind. Das hat mir sehr gut gefallen.]

When we aligned the personal and cultural background of the interviewees of this focus group, it seemed that their appreciation for the game æsthetic, their recognition of the performer’s accomplishments and their enjoyment or distaste of the sonic æsthetic of game_over_1.0.0 was connected to their cultural knowledge, personal education and former experiences.

In summary, we can trace all four kinds of meaningfulness mentioned above in this particular Case Study: structurally, visually and musically the work places strong emphasis on game æsthetics, strategies and achievable goals; it encourages ludic play while concurrently requiring a high level of “performative involvement” to counterbalance the dominant game æsthetic; and the performer’s decision-making process and varying control of the game allows them to pursue a musical performance that produces an engaging concert version of a multimedia art piece.

Marko Ciciliani — Kilgore (2017–18)

for electric guitar, drum pads and a joystick-controlled game system

In Marko Ciciliani’s audiovisual art game Kilgore (2017–18), spatial involvement — the exploration and learning of the game’s spatial domain (Calleja 2011, 4) and the virtual world that unfolds onscreen — stands in the foreground. The landscape in which the game is situated shows a mountainous area with steep canyons, a large lake with an island on which a house is placed, and a smaller lake in the middle of the terrain. Each of the two players moves individually through the landscape with their avatar while seeing the virtual surroundings from a first-person perspective. The performers run their individual versions of the same game, the visuals of which are shown in full-screen mode on two individual screens in the stage area. They cannot actually meet in the landscape, however, their individual actions influence the game as a whole.

Kilgore consists of altogether five sections. 9[9. At the time of writing this article, parts 4 and 5 of Kilgore were still in development. Parts 1 to 3 had been performed at two different venues in Belgium and Estonia but not yet in the framework of a lab concert of GAPPP. For that reason, I have not yet conducted interviews about audience or performer experiences with this piece but rather base my investigation on my personal performance experience of Kilgore and exchanges with the composer.] The computer animation in “PreLudus”, “InterPaida” and “PostLudus” (parts 1, 3 and 5, respectively) introduces the audience to the landscape and environment the players are supposed to explore while the musicians perform on electric guitar and drum pads. They ignore the visuals but play along an electronic soundtrack while following given musical game rules concerning phrasing, rhythm and interaction. In the two remaining and longer computer game sections, the musicians each operate using a traditional joystick but without providing any further instrumental input.

Kilgore offers both local and global agencies to the player-performers that they exploit in order to fulfil their objectives within its game-performance system. In “PreLudus”, the musicians play a musical game over the sonic backdrop of the changing visual scene displayed on screen (Video 2). The game here is not related in any way to the computer system and neither influences the other. Although while playing their instruments the musicians have no agency whatsoever with regard to the game evolving onscreen, they can in fact shape the music and the concert experience through their playing, thus gaining musical and performative agency. Involvement here is mostly performative, that is, the performer explicitly undertakes decisions in the pursuit of a musical performance.

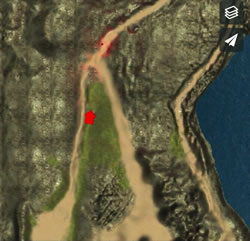

In the second part of the work, “Terrain”, the players have a clearly game-related local agency, namely finding their way through the mountain maze while hitting objects and collecting points, sinking a bronze object into a hole at the bottom of a drained lake and letting a bridge grow. A dimension of ludic involvement is added to spatial involvement (Calleja 2011, 4), emphasized for player and audience alike through the onscreen display of points earned and goals reached. By reaching and triggering certain points of the landscape or earning a certain amount of points, the players influence the course of the game and eventually open a secret access leading from the mainland to the island.

As Calleja states: “What makes travel in virtual worlds appealing is not only the affective power of their æsthetic beauty, but also the performed practice of exploring their technical and topographical boundaries” (Ibid., 77). And indeed, as a performer it is tempting to be entirely drawn into ludic play, be skilful and quick in navigating one’s avatar through the gorges and chasms of the mountains, locate and destroy red objects, collect live points by hitting the blue blocks that fall from the sky, dunk the bronze rock, be the first to trigger a new section, and so on. However, while being involved in the ludic play of Kilgore, the performers concomitantly influence the overall form and timing of the piece, the music itself and the visual experience of the audience — a sign of performative involvement.

To reach a confluence between the “goal and expectations” of the composer, performers and spectators, to further the “commonality of the [concert] experience” (Gurevich 2017), and to allow the audience to participate in the ludic and musical play of the game, the performers ideally supply the audience with a cognitive map. As Bjarke Liboriussen argues: “The cognitive map is a mental tool that aids its constructor in navigating the virtual world. At the same time, the cognitive map provides an overall sense of how the virtual world is structured and a sense of connectedness” (Liboriussen 2009, 222). To include the audience in the performers’ experience of involvement and connectedness, the players map the landscape and guide the audience members through the scene, and visually support the experience of hitting the red, blue or bronze objects. The latter is important, since hitting those objects is in general not accompanied by a typical “Hollywood” sound design, but often triggers only subtle changes in the audio environment. These changes may be difficult to perceive in the overall rich and dense sound environment.

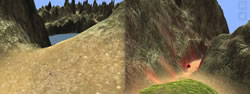

There are three different viewing perspectives that the performers can show to the concert audience, and each perspective is accompanied by a specific sound. The first perspective lets performers and audience traverse the mountains and canyons seen from the first-person perspective of their avatar (Fig. 2); movements in this virtual world trigger a low bass hum that is integrated in the dense sonic world of the landscape. Changes in the speed and density of the players’ movements cause variations in the sonic character of the hum.

Secondly, the performers can push a button on the game controller that lets the audience see the environment from a surveillance perspective, with a red arrow indicating the position and direction of the (invisible) avatar (Fig. 3). This is accompanied by a shrill, high signal sound that accentuates the change of perspective and can serve to add a rhythmic, contrasting, alerting element to the sonic backdrop and game. Last but not least, players can repeatedly hit the jump button, which plays a short, medium-high percussive sound and lets the avatar fly across the landscape (Fig. 4). Players need to acquire a certain degree of dexterity in the handling of the game controller to develop virtuosity in navigating the scene and, at the same time, the musical and performative options that go along with it.

Through their navigation of the environment, the performers build a visual map of the virtual world while at the same time shaping the overall musical experience. That way they let the audience visually, sonically and emotionally partake in the challenge of navigating the maze, and the audience and performers share what Calleja calls “a sense of habitation within the game environment” (Calleja 2011, 75).

The third part, “InterPaida”, is again characterized by musical agency and performative involvement. While the visual landscape changes from day to night and the camera glides over the newly erected bridge to the house on the islands, the guitarist adds to the musical and emotional landscape. The audience gets a glimpse of the environment the players will explore next. Kilgore simultaneously affords the players local and global agencies that are clearly game-related and that visually and musically feed back into the computer system, but also agency that is explicitly and only related to the visual and musical concert experience.

In Kilgore, the emphasis ostensibly lies on the visual exploration of the mountainous landscape and the objectives the players have to fulfil. However, the composer counterbalances each of the main, spatially and ludically dominated sections (2 and 4) with those segments in which the virtual camera roams the virtual scene while the players are given clear musical and performative tasks. Consequently, the player-performers’ involvement fluctuates between performative and spatial. Meaningfulness with regard to technical skills, musical objectives and the sharing of artistic experiences with the audience are the main motivators and factors for the performers.

In the case of the works by Ressi and Ciciliani discussed above, the computer system operates as an autonomous, generative system that, on the one hand, reacts to the performer’s input and, on the other hand, acts as an independent agent that feeds unforeseen contingencies into the game that the performer cannot necessarily control. Thus the works have two sources of dynamic behaviour: the performer’s actions and the computer’s independent agency. The manner in which the computer’s dynamic interaction is designed shapes the agency and involvement of the performer in a meaningful way.

Is it a game or a concert piece?

In order to shed light on the question of what makes a GAPPP work appear as a game rather than a concert work and how that is connected to “performative involvement”, it will be useful to juxtapose the game work Tonify by Martina Menegon and Stefano D’Alessio to the previous case studies.

Case Study 3

Martina Menegon and Stefano D’Alessio — Tonify (2017)

performative audiovisual game

Martina Menegon and Stefano D’Alessio’s Tonify is an interactive audiovisual work for two participating audience members. Their main goal was to create an “interaction with the audience” and solve the question of how to make this interaction a game, “how to make it funny to watch, entertaining to watch, but also [funny] to do” (Menegon and D’Alessio cited in Pirchner 2017a).

The players perform while standing on the stage in front of their individual computer screens, facing the audience. The players’ facial expressions are projected and superimposed on a large screen behind them; the screen displays of the two game computers are projected on the left and right sides of the players’ image, allowing the audience to follow the course of the game. During the game, each player is presented in turn with one of four basic emoticons that they try to imitate with their own facial expressions. The emoticons change every five seconds. The different background colours that reflect from the computers illuminate the players’ faces. Each player’s expression is individually captured by a face-tracking system, a neural network that detects parameters of the facial expression of the player. On the basis of machine learning, each computer had prior learned what a neutral, surprised, angry or happy face looks like, so it is able to detect how happy, neutral, surprised or angry the player looks and if it matches the emoticon displayed on the computer screen.

Whenever a new face appears on the computer screen, a sonic texture is initialized that corresponds to one of the four facial expressions (Video 3). A humming bass, for instance, accompanies the neutral face, a jumpy soundscape plays when the surprised expression appears. The way the audio is processed depends on the “correctness” of the imitation by the performer. When the performer imitates the emoticon wrongly or inaccurately, the sound becomes distorted or otherwise processed; when they imitate it correctly, we hear the original, unprocessed sound.

The computer scores the personal imitation skills of the two performers. The correctness level of the imitation is shown in form of a slider line and points that indicate the total scoring on the individual monitors as well as the stage screen. At the bottom of the main screen, to the right and on the left, the audience sees the user names of the players; in the middle of the screen a slightly distorted, semitransparent mapping of both performers’ faces is projected (Fig. 5). Depending on the correctness of their imitation, one or the other face is more in the foreground than the other. “Shared involvement” (the player competes with other agents in the game) is the Callejan category at the basis of the emotions this game triggers (Calleja 2011, 4).

The “instrument” the performers use is their own face (Fig. 6). The interface, although highly technical and sophisticated, is easy to understand and to work with. No prior education is needed for the performers’ actions, which is to “contort” their face in the right way to score points. They stand in a competition to each other, in an “athletic” contest measuring the best manipulation of their face muscles in combination with the fastest response time. The performance is rapid and the core issue is “the execution of an action by a participant, an action that may succeed or fail” (Ibid., 58).

The individual player’s agency is clearly defined and restricted to the task of imitating the emoticons shown to them; contingency is minimal. The seemingly obvious goal is to score high and win the game. According to the game designers, the idea is even simpler. They aim for the emotional involvement simply through the pleasure of playing the game and earning points along the way:

[T]here is not really a goal or something, it’s just like the pleasure of gaining points, you know. I was reading this article in which they found out that even if the number [of points shown] is not connected to what you are doing, it is more enjoyable to do, if you have the numbers. (Pirchner 2017a)

However, in theory the goal could be changed from “not winning” to “entertaining the public”, from ludic play to musical play, from playing a game to performing an artwork. In that case, the performers could manipulate the sonic æsthetic range of the game by intentionally “failing” at their tasks and thus evoking stronger audio processing or distortion, much in the sense of Flanagy’s aforementioned “subversive play”. Visually, they could work with and exaggerate their facial expression to entertain visually and add to the situationally comic nature of the performance. This would be a way to add the model of performative involvement to the mix of what is happening on stage. In reality, though, the computer system reacted not in a generative way but rather linear, such that the changes in music as they related to the performers’ actions were discernible to the trained ear only, the performative agency limited to subtle transformative changes in sonic colour.

Asked where our audience members would position Tonify on a scale from game to artwork and how important the actual performance factor was, the interviewees in Focus Group 1 tended to view the work more as a game than a musical performance:

I first asked myself, what is a game, actually? I would say that in a traditional sense it is something you can win or lose, it is something you can play against a bot or against a human adversary. And, of course, this second performance with the face tracking [Tonify] seems like the best to qualify for a game. Something like that is, for me, obviously a game. (Pirchner 2017b, Interviewee 1) 10[10. Ich hab mich erstmal gefragt, was ist überhaupt ein Spiel, ein Game und ich würde sagen, in traditionellem Sinne ist es ja etwas, das man gewinnen oder verlieren kann, das man mit einem Bot oder mit einem Menschen spielt. Und da ist mir natürlich die zweite Aufführung mit dieser Gesichtserkennung [Tonify] am ehesten als Spiel aufgefallen. Das war für mich direkt ein Spiel.]

That [piece] with these facial expressions… in that piece the [concert] performance is not that relevant. (Pirchner 2017b, Interviewee 2) 11[11. Das [Stück] mit diesen Gesichtsausdrücken… bei dem ist die [Konzert]performance nicht so relevant.]

When we refer to the statement by Salen and Zimmermann mentioned earlier that “[m]eaningful play occurs when the relationship between actions and outcomes in a game are both discernible and integrated into the larger context of the game” (Salen and Zimmermann 2004, 34), we can clearly see the difference in relation to the previous case studies. In Tonify the larger context of the game is meant to be entertainment. “To provide fun” and to make Tonify playable for everybody is the ultimate goal for the creators. Accordingly, the players don’t need to enhance their technical capabilities, there are almost no strategies or objectives that point beyond the relatively simple task of smiling, frowning, looking sad or looking serious. The visual and musical outcome is established from the very beginning and only marginally controllable or manipulable. This doesn’t make it a less successful work; on the contrary, audience members stated that they would like to try the piece themselves or even play it at home.

In conclusion, I would therefore state that dynamic interaction with a computer system does not in itself evoke “performative involvement”. Performative involvement is linked to aforementioned situations of meaningfulness, it thrives in works that are multidimensional and that offer layers allowing the player-performer to musically and/or visually shape the work itself as well as the visual and sonic experience of the audience in the concert situation. The ultimate goal for me would be to reach a confluence between the composer, performer and spectator’s “goal and expectations” and “commonality of cultural experience,” (Gurevich 2017) in order to enhance the artistic experience for all.

Bibliography

Calleja, Gordon. In-Game: From immersion to incorporation. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 2011.

Ciciliani, Marko. Kilgore (2017–18), for electric guitar, drum pads and a joystick-controlled game system. Trailer. Performed by The Third Guy: Primož Sukić (electric guitar and game controller) and Ruben Orio (percussion and game controller) at the Institut für Elektronische Musik und Akustik’s Cube in Graz (Austria) on 6 March 2018. Vimeo video “‘Kilgore’ for two performers and a game system by Marko Ciciliani (2017/18)” (2:30) posted by “Marko Ciciliani” on 11 January 2018. http://vimeo.com/250603699

Di Scipio, Agostino. “‘Sound is the Interface’: From interactive to ecosystemic signal processing.” Organised Sound 8/3 (December 2003), pp. 269–277.

Flanagan, Mary. Critical Play: Radical game design. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 2009.

Gurevich, Michael. “Skill in Interactive Digital Music Systems.” In The Oxford Handbook of Interactive Audio, pp. 315–332. Edited by Karen Collins, Bill Kapralos and Holly Tessler. Oxford University Press, 2017.

Liboriussen, Bjarke. “The Mechanics of Place: Landscape and architecture in virtual worlds.” Unpublished PhD thesis, Institute of Literature, Media and Cultural Studies, University of Southern Denmark, 2009. http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Bjarke_Liboriussen/publication/261555579_The_Mechanics_of_Place_Landscape_and_Architecture_in_Virtual_Worlds/links/02e7e534a7395dd70a000000.pdf [Last accessed 11 February 2018]

Lüneburg, Barbara. Interview with Szilard Benes on his performance practice prior to his 8 February 2017 performance of Christoph Ressi’s game_over_1.1 at the Institut für Elektronische Musik und Akustik’s Cube in Graz (Austria). GAPPP — Gamified Audiovisual Performance and Performance Practice, 7 February 2017.

Menegon, Martina and Stefano D’Alessio. Tonify (2017), performative audiovisual game. Trailer of a performance by the composers at the Institut für Elektronische Musik und Akustik’s Cube in Graz (Austria) on 9 September 2017. http://youtu.be/YCdNvl4EEIs

Oliva, Costantino. “On the Ontological Status of Musical Actions in Digital Games.” PCG2017: Action in Computer Games. Proceedings of the 11th International Philosophy of Computer Games Conference (Kraków, Poland: Faculty of Polish Studies, Jaegellonian, 29 November – 1 December 2017). http://2017.gamephilosophy.org

Pirchner, Andreas. Interview with composers Stefano D’Alessio and Martina Menegon prior to the performance of their piece Tonify in the framework of the 9 September 2017 GAPPP lab concert at the Institut für Elektronische Musik und Akustik’s Cube in Graz (Austria). GAPPP — Gamified Audiovisual Performance and Performance Practice, 9 September 2017.

_____. Interview with the participants of Focus Group 1 in the framework of the 9 September 2017 GAPPP lab concert at the Institut für Elektronische Musik und Akustik’s Cube in Graz (Austria). GAPPP — Gamified Audiovisual Performance and Performance Practice, 9 September 2017.

Ressi, Christof. game_over_1.0.0 (2017), for clarinet, sound module, sensors and computer game software. Performed by Szilard Benes (clarinet) and Christopher Ressi at the Institut für Elektronische Musik und Akustik’s Cube in Graz (Austria) on 8 February 2017. Vimeo video “game_over_0.1.1” (12:27) posted by “Christof Ressi” on 10 February 2017. http://vimeo.com/203473492

Rowe, Robert. Interactive Music Systems. 1993. http://wp.nyu.edu/robert_rowe/text/interactive-music-systems-1993/chapter-1-interactive-music-systems [Last accessed 31 July 2017]

Sackl-Sharif, Susanne. Interview with the participants of Focus Group 2 in the framework of the 8 August 2017 GAPPP lab concert at the Institut für Elektronische Musik und Akustik’s Cube in Graz (Austria). GAPPP — Gamified Audiovisual Performance and Performance Practice, 8 August 2017.

Salen, Katie and Eric Zimmermann. Rules of Play. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 2004.

Social top