Organizing for Emergence

Computer vision and data mining as co-creative devices

Drawing on Jane Bennett’s theoretical position of “thing-power,” Erin Manning and Brian Massumi’s philosophical notion of “organized emergence” and Timothy Morton’s dark ecology project, I propose a series of thinking-in-the-making moves that considers the use of computer vision and data mining as co-creative and emergent devices. This research is motivated by the shift in my sonic arts practice away from fixed-media formats to the exploration of non-linear audiovisual systems.

Analogous to what Manning and Massumi call “the friends,” these accompanying influences “activate a process [and] force that acts as a differential within the ongoing movement of thought… creating an intensive passage between past and future outsides… a complex polyphony…. Thought not as already-constituted but as a force for creative thinking-feeling” (Manning and Massumi 2014, location 1241–1253). Here Manning and Massumi provide an interpretation of Gilles Deleuze’s notion of the intercessors: “the felt force that activates the threshold between thinking and feeling” (Ibid., 1243). Throughout this article these felt forces will be interwoven with how I experience, contextualize and ultimately describe the making-doing-thinking of my creative research.

To support my position, I critique two of my recent non-linear audiovisual installations, Piano at the End of a Poisoned Stream (2017) and Cathedral (2017), which emerged from field recordings in the Salton Sea and Sequoia National Park respectively. Using computer vision 1[1. I have experimented with various computer vision systems including David Rokeby’s Very Nervous System (VNS), Miroslav Spasov’s ENACTIV, Alexander Refsum Jensenius’s Motiongram, and Jean-Marc Pelletier’s cv.jit library. While all these systems offer exciting avenues of creative exploration, Pelletier’s cv.jit library is more suitable for the analysis and extraction of information from the videos in my creative research.] and data mining 2[2. I use the term data mining via R. Luke Dubois, whose creative research explores the use of data that has been gleaned from real world events.], these works explore material agency from these situated encounters in a non-linear æsthetic. Moreover, configuring these audiovisual installations, wherein the materiality of the visuals became triggering agents, led to my considering the overall process as being organized for emergence and that such apparatus are co-creative devices. Beyond technical considerations, these ideas introduced a way of thinking and being in artistic practice that, as described by Manning and Massumi, is “an environmental mode of awareness.”

The making-felt of a co-compositional force that does not yet seek to distinguish between human and nonhuman, subject and object, emphasizing instead an immediacy of mutual action, an associated milieu of their emergent relation. (Manning and Massumi 2014, location 164)

Intercessors and Felt Forces (Part One)

Jane Bennett — Thing-Power

Music… is better suited for acknowledging and translating the call of things. (Bennett 2011)

Bennett’s discourse on “thing-power” articulates the lure and effective capacity various objects have had on my field recording projects and, in turn, on the making of non-linear audiovisual installations such as Piano at the End of a Poisoned Stream. A crucial implication of “thing-power” is Bennett’s recasting of everyday inert objects into active and vibrant material. In so doing, Bennett breaks with the subject and object dichotomy by giving agency to the energetic vitality intrinsic to matter, and the active, earthy and complex entanglements of human and nonhuman encounters (Bennett 2010, location 333).

Earthy bodies, of various but always finite durations, affect and are affected by one another. And they form noisy systems or temporary working assemblages that are, as much as any individuated thing, loci of effectivity and allure. (Bennett 2015, 233)

While Bennett locates “thing-power” within the traditions of Baruch Spinoza’s “conatus”, Henry Thoreau’s “force of the Wild,” and Lucretius’ “primordia,” her project is more a literal response to a particular set of objects (Bennett 2010, location 319). This “call of things” (Bennett 2011) occurred one sunny spring day in Baltimore over a storm drain grate and included:

one large men’s black plastic work glove

one dense mat of oak pollen

one unblemished dead rat

one white plastic bottle cap

one smooth stick of wood (Bennett 2010, location 344).

Bennett’s surprise encounter with this assemblage of things or, to use Bruno Latour’s term, “expressive actants,” (Bennett 2011) set in motion a vibratory experience that oscillated between “stuff to ignore, … stuff that commanded attention” and a sensation of disgust and dismay (Bennett 2010, location 347). Consequently, Bennett negotiates a line of discourse that contemplates the “active expressive or calling capacity of things” (Bennett 2011). Thus, in Vibrant Matter, Bennett “turn[s] the figures of ‘life’ and ‘matter’ around and around, worrying them until they start to seem strange, in something like the way a common word when repeated can become a foreign, nonsense sound” (Bennett 2010, location 55). It is out of this turning that her vibrant materialist concept of “thing-power” emerges.

Bennett is clear that her brand of materialism is not that of the long tradition of Vitalism, which infuses spirit, soul or God into objects (Bennett 2011). Her goal instead is to acknowledge and give greater recognition to the affective and agential capacities of natural and artifactual things (Bennett 2004, 349). Thus, Bennett’s “thing-power” is an attempt to “tune the human body, for rendering it more susceptible to the frequencies of the material agencies inside and around us” (Bennett 2011). Bennett claims her reasons for doing so are:

to see what happens to our writing, our bodies, our research designs, our consumption practices, our sympathies, if this call from things is taken seriously. Taken, that is, as more than a figure of speech, more than a projection of voice onto some inanimate stuff, more than an instance of the pathetic fallacy. What if things really can in some underdetermined way hail us and offer a glimpse through a window that opens of lively bodies that are unparsed into subjects or objects. (Bennett 2011)

Bennett’s “thing-power” provided a theoretical position from which to break with the duality of “subject” and “object”.

Bennett, therefore, turns to the rubric of material agency, believing it to be a more potent way to problematize human exceptionalism, “the human tendency to understate the degree to which people, animals, artifacts, technologies, and elemental forces share powers and operate in dissonant conjunction with each other” (Bennett 2010, location 883). She thus develops her theory of distributive agency via Spinoza’s “affective bodies” and Deleuze and Guattari’s “assemblage theory” (Ibid., 639). To support her theory Bennett examines different sites and occurrences of distributive agency: the 2003 North America power blackout; American consumption practices and the crisis of obesity; the call of things for hoarders; and, more recently, through the agency of the text-body of poetry. Bennett’s account of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass and James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake resonates most succinctly with my research as she brings attention to the particular kinds of agency, distinctive effects and capacities available in the material configuration of the text-body of the poems (Bennett 2015, 234). Bennett ably shows how, in reading a certain configuration of words, one’s sensibilities can change and attune in different directions. For example, after reading Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, Bennett cannot help but think of the uncut hair of Graves while stepping on her lawn. Of this Bennett says:

The effectivity of a text-body, including its ability to gesture toward a something more, is a function of a distributive network of bodies: words on the page, words in the reader’s imagination, sounds of words, sounds and smells in the reading room, and so on, and so on — all these bodies co-acting are what do the job. (Bennett 2012)

For my purposes, I replace the text-body with the sonic, visual and data-body, and the poem with non-linear audiovisual installation. The sonic-body is understood here not as sound in itself — in the manner of reduced listening or Pierre Schaeffer’s objet sonore — but as being embedded in the different agential “intra-actions” of the material world (Barad 2007, location 2778–2808). 3[3. Karen Barad’s conceptual shift from interaction to “intra-action” signifies the ongoing process of becoming and the reconfiguring of the world in a performative ontology. The anthropocentric understanding of creativity shifts to one of a relational and performative ontology where the “intra-actions” constitute a dynamic mode of artistic practice. Thus, Barad’s “intra-activity” constitutes a conceptual shift from traditional notions of causality by taking into account the performative aspects of “material bodies (both human and nonhuman).”] The “distributive network” of the sonic-body includes the object and space in which the sound is ensounded and the forces that influence the sonic resonation to occur (Ingold 2011, 136–139). 4[4. Tim Ingold’s notion of “ensounded” suggests that we hear in sound rather than hearing sound. Ingold objects to the term “soundscape”, which he believes positions sound as an object rather than an experience.] Similarly to Bennett, the sonic-body can be considered as a “function of a distributive network of bodies” including the situated environments and their histories.

Accordingly, I consider data as matter and draw from Bennett’s concept of “thing-power” — as being part of the “active, earthy, a complex entanglement of human and non-human encounters” (Bennett 2010, location 333). Thus, the material configuration of the “data-body,” like the text-body, can change one’s sensibilities to attune in different directions. To this end, I believe Bennett’s “thing-power” provides a viable way to introduce a new vocabulary that gives an account of the types of relations, responses and response-ability we find ourselves entangled in. As Bennett suggests: “sound and music is the most fecund of sites to annunciate the call of things” (Bennett 2011).

Ultimately, Bennett’s “thing-power” is grounded in an ecological discourse, with the caveat of a comprehensive revision of the holistic platform of deep ecology (Ibid.). “Thing-power” is a method to achieve this goal as it fosters a “greater recognition of the agential powers of natural and artifactual things, greater awareness of the dense web of their connections with each other and with human bodies, and, finally, a more cautious, intelligent approach to our interventions in that ecology” (Bennett 2004, 349), and “with less violence towards a variety of bodies” (Bennett 2011). Thus, being in creative practice with Bennett’s “thing-power” provided a theoretical position from which to break with the duality of “subject” and “object” and comprehend the different directions and sensibilities at work in various encounters and assemblages of things.

Organized for Emergence (Part One)

Excerpt of the author’s Research Journal from June 2014 at Bombay Beach, located on Salton Sea in southern California:

The indexical signs of the human and nonhuman now litter Bombay Beach, which has been described as “the most depressing place in California” (Riggs 2010). Once Denton and I had adjusted to the initial shock of this environment, we proceeded to record these indexical signs. Denton finds himself visually drawn to the monotonous awe of water reflections, birds in flight and the seemingly endless convoy of cattle trains that shimmer in the desert heat, on their journey from Mexico (Fig. 1). For my part, I became transfixed with the numerous objects scattered throughout this landscape: rusty metal objects sticking out of the ground, wooden refuse from dilapidated buildings, sections of concrete slab, plastic bags entangled and flapping in dead bushes, and a lone broken piano (Fig. 2). Using contact microphones, I recorded the sonic textures and tones by tapping, plucking and playing these objects. Equally striking was the sound resounding at the water’s edge. Primarily comprised of crushed fish and bird bones (Fig. 3), the sonic quality activated by wave and human footsteps has a sharp percussive high-pitched resonance. I captured this using a hydrophone mic.

This journal entry occurred during a gruelling three-week field recording journey that brought my colleague, New Zealand film and video artist Andrew Denton 5[5. Denton and I are long-time collaborators of audiovisual works.], and I first to the southern part of California, then to Los Angeles and subsequently into Sequoia National Tree Park, Death Valley National Park and Yosemite National Park, before moving onward to Reno and Salt Lake City. It recounts the shift of attention that being in this environment caused in my responsive listening, recording and creative tendencies. Qualities and sensibilities emerged that took over and influenced the experience and methods of recording, which I now consider to be performative: “the ones we see and hear, the ones that lay claim to our responsiveness and by acting on us tacitly restructure how we sense the world and come to act as we do” (Butler 2014). My responsiveness to these elements became the triggering mechanisms from which emerged Piano at the End of a Poisoned Stream. The tendencies that surface are intrinsically linked to being in these environments. What is set in motion is a complex relational flow between the inside and outside, attunement to which takes time. According to Bennett it requires “a cultivated, patient, sensory attentiveness to nonhuman forces operating outside and inside the human body” (Bennett 2010, location 169).

While field recordings often begin with the matter-of-fact process of dealing with equipment (such as making sure all batteries are charged), these functional and environmental influences become an operative (performative) agent in the collection of materials and making the installations. Accordingly, I contextualize this way of being in environments through Manning and Massumi’s philosophical notion of “event-based ecology of experience” (2014, location 91). Here they ask: “What new forms of collaborative interaction does… research-creation-based speculative pragmatism imply? What kinds of initial conditions are necessary? What does it mean to organize for emergence?” (Ibid., 1615). For me, “initial conditions” and “organizing for emergence” are important considerations in how I have come to consider my creative research. An example from my research is this three-week field recording session with Denton. For my part, I had no programmatic structure as to what I would record or what works would emerge. In essence, the choice to participate on this trip was the initial condition out of which emergence was organized and enlisted as a technique. Of this Manning and Massumi say:

This idea of research-creation as embodying techniques of emergence takes it seriously that a creative art or design practice launches concepts in-the-making. These concepts-in-the making are mobile at the level of techniques they continue to invent. This movement is as speculative (future-event oriented) as it is pragmatic (technique-based practice). [Manning and Massumi 2014, location 18]

Thus, being in different environments with other creative practitioners is an initial tool and technique through which the process of emergence is organized, becoming an essential method of the practice — an event and working-out process that mobilizes an exchange of perspectives. Questions that have repeatedly emerged during these field recording projects are how to engage the elements found in these environments as a co-creative and performative device, and what effect they would have in a non-linear audiovisual installation platform. From my early experiments with different techniques, I have come to employ the processes of computer vision and data mining. It is my position that in the context of each location, using the elements found therein as co-creative devices in a non-linear audiovisual installation platform enables different directions of creative practice that, in turn, draw forward alternative ways to experience and think about the world.

Piano at the End of a Poisoned Stream

A co-poiesis is occurring here. (Manning and Massumi, 2014)

In 1905, when the Colorado River swelled and breached its banks, the water ran into the Salton Sink, a geographical region 220 feet below sea level. After two years of continuous flow, a 15-by-35 mile lake formed, which became known as the Salton Sea (Salton Sea Authority 1997). As California’s newest and now largest lake, the Salton Sea became a favourite getaway spot for nearby Los Angeles and San Diego residents. During the 1950s and ’60s, Bombay Beach, which is located on the lake’s eastern side, became a prosperous resort town filled with sunbathers, water skiers and yacht club parties. During the 1970s, however, it became clear that the ecosystem of the Salton Sea was quickly deteriorating. With no drainage outlet and little to no annual rainfall, the inflow of industrial pollutants and untreated sewage began to increase the lake’s salinity and caused the water to deoxygenate. What had become an angler’s well-stocked paradise quickly transformed into a rotten layer of dead fish and birds.

On the field recording trip to the Salton Sea, after parking the vehicle and venturing into this environment, the odour itself stopped me in my tracks. The shoreline was littered with dead fish and birds and human objects in varying stages of decline, all of which were covered with a dusty white mixture of salt and dried mud. Once I had adjusted to the initial shock of this environment, I proceeded to record the indexical signs of the human and nonhuman that now littered Bombay Beach. As noted in my Research Journal entry above, I became transfixed by the numerous objects scattered throughout this landscape: rusty metal objects sticking out of the ground, wooden refuse from dilapidated buildings, sections of concrete slab, plastic bags entangled and flapping in dead bushes, and a lone broken piano.

At the time of this field recording, I had not yet researched the theoretical position of Jane Bennett. However, this experience at the Salton Sea motivated me to find ways to identify and engage with the feeling of strangeness that surfaced while recording in this location. Bennett’s development of “thing-power” from her chance encounter with a “glove-pod-rat-cap-stick” (Bennett 2004, 350) resonated with my chance encounter with the objects found at Bombay Beach and in turn influenced the direction of my research and the outcomes of the practice. As Bennett says: “Thing-power gestures toward the strange ability of ordinary, man-made items to exceed their status as objects and to manifest traces of independence or aliveness, constituting the outside of our own experience” (Bennett 2010, location 218). Thus, the objects found at Bombay Beach had “a certain effectivity of their own, [an] irreducible degree of independence from the words, images, and feelings they provoke in us” (Ibid.).

When working with the audiovisual material collected from Bombay Beach, I began by exploring different location subjects including water (Fig. 4), birds in flight (Fig. 5) and the broken piano. Denton shot this footage at 200 frames per second, which causes a slowing-down process that draws out visual elements that would not otherwise be captured in normal mode (Denton 2016a). For example, the close-up footage of the piano strings, captured at 200 frames per second, draws out subtle movements in the shadows of the strings (Video 1). 6[6. This piano footage was captured on our second trip to the Salton Sea, where the broken piano had sustained further damage from being set on fire.] This footage is very hypnotic, beautiful and disturbing, and becomes a transformative element in the installation. Similarly, the blue water footage and birds in flight were captured at 200 frames per second using an 800 mm lens. Specific to the water footage, Denton states that this method of capture enabled him to “isolate certain elements of the frame that can be in focus and others that aren’t, like blown out sun-on-water reflections [Video 2] or industry-in-the-distance image [Video 3]” (Denton 2016b). For me, combining these three elements into the final installation — the water, birds and piano — holds open a space that enables the complex polyphony of this ecology to be expressed.

To combine these elements in a gallery space, a four-panel water video (Figs. 6–7) was projected on a large fabric screen along the back wall. The piano videos were routed to three 42-inch TV monitors and positioned on the floor (Fig. 8), while the bird footage was routed to four 20-inch monitors and separately onto 12 iPads positioned around the gallery (Fig. 9). Apart from the iPad videos, each component is allocated to an individual laptop and coded in Max 7 to randomly select between a folder of videos: 14 in the water folder, 30 in the piano folder and 4 in the bird folder.

Accordingly, the bird in flight footage is coded to trigger the sonic layers of this installation. As each bird flies off screen right, a trigger is sent to a separate computer patch (Fig. 10) containing a significant number of field recordings and human-object interactions recorded at Bombay Beach. Given the various methods of recording sound — using contact microphones, a hydrophone, an AMT M40 piano microphone system and two-channel panned shotgun microphones — an alternate field of sonic material was captured that, for me, shifts the temporal perspective of this environment. The final installation thus includes elements from all sonic fields, all triggered by the birds in flight footage.

Additionally, I sonified historical graphs of the salinity in the Salton Sea and the changes of fish biomass (Hurlbert et al., 2007). Using the Image Synth functionality in the programme MetaSynth, these images were translated into sonic motifs in conjunction with a sampler instrument containing sounds recorded from the burnt piano; the result is a pitch-shifted phrasing based on the graphs.

The last sonic parameter of Piano at the End of a Poisoned Stream includes convolution using the HISSTools Impulse Response Toolbox. 7[7. Developed by Alex Harker and Pierre Tremblay at the University of Huddersfield and released in 2012, this set of externals enables real-time convolution.] For this process, I selected five underwater impulses recorded at the Salton Sea to convolve with a number of the piano recordings. During the running of the installation, these impulses are coded to randomly change, which results in different sonic perspectives.

The number of audio samples available for triggering by the birds in flight footage is 80. The lengths of these audio files vary considerably because of the different methods of interaction and recording. The result is an oscillation of environmental sounds and piano improvisations moving from foreground to background depending on the random triggering functionality. Because of this, and with the other components of the work, the final non-linear installation (Video 4) moves through different temporal perspectives and, for me, evokes (via Timothy Morton) the weird weirdness of this environment.

Intercessors and Felt Forces (Part Two)

Timothy Morton — Dark Ecology

With dark ecology, we can explore all kinds of art forms as ecological: not just ones that are about lions and mountains, not just journal writing and sublimity. The ecological thought includes negativity and irony, ugliness and horror. (Morton 2010a, 17)

Timothy Morton’s dark ecology project and his books The Ecological Thought and Hyperobjects: Philosophy and ecology at the end of time have intersected at different moments with my practice-based research. Morton’s ecological thoughts propose a way of thinking and being (in which he considers thinking, in and of itself, an ecological event) that embraces ambiguity, uncertainty and the uncanniness of the entangled mesh. Drawing on Graham Harman’s object-oriented ontology philosophy, Morton offers his notion of the “strange strangers” (Morton 2013a, location 190) and “weird weirdness” (Morton 2016, location 155) as an alternative form of ecological awareness in which “hesitation, uncertainty, irony, and thoughtfulness are put back into ecological thinking” (Morton 2010a, 16). Morton is a strong advocate for music and art, stating: “art forms have something to tell us about the environment, because they can make us question reality” (Ibid., 8).

Morton describes “the mesh” with words like “finely woven”, “threading”, “interconnectedness” and “entangled” (Morton 2013b, 75; Morton 2010a, 28). His discourse, however, quickly moves to the core of his dark ecology project; that is, to identify the uncanniness that results when realizing the immensity and, at the same time, the nearness of “the mesh” (Morton 2010b, 275). Accordingly, Morton substituted these descriptive terms with “the mesh” as a way to disrupt some of the sentimental rhetoric of deep ecology (Morton 2007, 2 and 6) and to challenge the Romantic perspective of Nature as “That Thing Over There” (Ibid., 1). Of this Morton claims: “The more we know about life forms, the more we recognize our connection with them and the stranger they become” (Morton 2010a, 17). Thus Morton’s “strange strangers” emerge from his ecological thought that imagines a multitude of entangled life forms and the radical intimacy that dwells therein (Ibid., 8–15). For Morton, there is much to be gained in this intimacy with the “strange stranger,” in that we realize how hopelessly we are entangled in “the mesh” (Morton 2010b, 293). With this realization comes responsibility, out of which the idea of the upper-case “N” of Nature is problematized and abandoned (Morton 2007, 1). Morton further suggests that “the very idea of ‘nature’ which so many hold dear will have to wither away in an ‘ecological’ state of human society” (Ibid.). What emerges from this ontological shift is a causal dimension that, as Morton proposes, is the æsthetic dimension (Morton 2013b, 24). Thus, for Morton, æsthetic events

are not limited to interactions between humans or between humans and painted canvases or between humans and sentences in dramas. They happen when a saw bites into a fresh piece of plywood. They happen when a worm oozes out of some wet soil. They happen when a massive object emits gravity waves. When you make or study art you are not exploring some kind of candy on the surface of a machine. You are making or studying causality. The æsthetic dimension is the causal dimension. (Morton 2013b, 19–20)

For my creative research, thinking in terms of the mesh and æsthetic events provided a way to consider the interwoven conditions and influences out of which emerge the practice and non-linear audiovisual installations. Accordingly, Morton’s dark ecological considerations of the “strange stranger” offered insightful ways to reconfigure my ideas of interconnectedness and thus identify with the weirdness that often surfaced while on field recording projects. Here, Morton’s notion of the “weird weirdness” resonates most succinctly.

Morton consolidates his notion of “weird” by first drawing on the Old Norse meaning of the word, urth, meaning “twisted” or “in a loop” (Morton 2016, location 131). Subsequently, weird is identified to mean causal, destiny, worth and becoming (Ibid.). From his dark ecology project, Morton’s “weird weirdness” is “a turn or twist or loop, a turn of events. … strange of appearance. … In the term weird there flickers a dark pathway between causality and the æsthetic dimension, between doing and appearing…” (Ibid.).

The capacity to experience the weird weirdness in the field requires, as Bennett suggests, “that one is caught up in it. One needs, at least for a while, to suspend suspicion and adopt a more open-ended comportment. If we think we already know what is out there, we will almost surely miss much of it” (Bennett 2010, location 200). In this mode of attention, the incurred moments of “weird weirdness” become an operative co-creative element. In turn, responsiveness to such weird encounters became an affective and performative aspect in my ecology of practice. Thus through Morton’s theoretical and philosophical provocations I began to consider my artistic interest in non-linear procedures from an ecological awareness that considered the “dark-depressing” and “dark-uncanny” (Morton 2016, location 128). Not only from the context of being in different environments — from which the works evolve — but also as a way to be in and sense the world differently.

Organizing for Emergence (Part Two)

Excerpt of the author’s Research Journal from July 2014 in the Sequoia National Forest in central California:

The field recording in Sequoia National Park was strange. I found being bussed to the entrance of a long descending walkway, coupled with the overwhelming amount of tourists, all coming to gaze (and capture through their cameras) the largest giant Sequoia trees in the world, disturbingly sad — a weird procession. The way the sunlight shafts popped through the trees from my dust-covered window on the bus looked like stained glass. Once off the bus and “plugged in” 8[8. Being “plugged in” refers to having my headphones on and recording. I use this term to tell my colleagues “do not disturb.”], I became transfixed by the sonic qualities of this environment. The natural reverb of the forest is similar to a very large cathedral. The chatter of the tourists, interjected with the scurrying flip-flops of children, footsteps of their parents and the haunting sounds of crow calls created a weird musical polyphony. Descending the paved trail to finally arrive at the main attraction, General Sherman — the largest Sequoia tree in the world — the concentration of voices became sonically dissonant. The overlapping languages coupled with the natural reverb of the forest morphed into a strange, yet beautiful hypnotic choir — like in a cathedral. I slipped into a slowed down, somewhat meditative state. Punctuating this vocal polyphony were the various mechanical sounds of cameras and footsteps.

My research journal entries best convey the shift of experience (Morton’s weird weirdness) — or Guattari’s “far off balances” — that occurred during this field recording session: from the stained glass metaphor of light through the dust-covered bus window, to feelings of strangeness being transported to the descending walkway that leads to General Sherman, to hearing the overlapping voices reverberating in the forest as a cathedral-like polyphony punctuated with footsteps and different camera sounds. My responsiveness to these elements informed the Cathedral installation.

Later, when listening to the audio field recordings, the quality of the voices in this environment reinforced the cathedral metaphor, from which a complex polyphony of thinking-feeling emerged. At the time of this field recording session, an emotional state emerged, similar to what Morton calls the “dark-depressing” and “dark-uncanny” (Morton 2016, location 128). For my part, along with the numerous disturbing locations explored, the moments of being “pulled aside” by security guards (with guns) questioning what I was doing in various locations were influential. On one occasion, I thought I would either be thrown in jail or escorted to the Canadian/USA border. So, as this trip proceeded, a “dark-depressed” emotional state settled in. As we moved through different environments, I began to contemplate: “What is the purpose of an art form that is embedded in time and place?” By the time we arrived in Reno and submerged ourselves in the casino environment, Denton and I were emotionally exhausted. From the polluted wastelands of the Salton Sea to the addictive gambling activities of Reno, the performative agency of human and nonhuman bodies was overwhelmingly disturbing.

When I initially considered my question — the purpose of an art form embedded in time and place — I had no answer. I could only reflect on the fact that I had been capturing and exploring the day-to-day situated sounds and encounters in the world for some time, and that these activities were motivated by my various creative curiosities. On engaging with the researchers presented here, I began to contextualize the making-doing-thinking and feeling of my ecology of practice as part of a larger performative “intra-action” with the world (via Barad); something that lays claim to my responsiveness, out of which I come to act as I do (via Butler). The lure to record objects found in different environments is, as Bennett describes it, the “call of things,” which music is “better suited for acknowledging,” and the “weird weirdness” I have often felt in different field recording encounters can be thought through with Morton’s dark ecology project, which is attuned to the “shifting, ambiguous stage set.” The result, for me, was a deeper connection with the worth of such an artistic practice, as well as a broader method and sensibility for considering the entanglements at work between different bodies (human and nonhuman), in a non-reductive and contingent way.

Cathedral

What art really does is generate “far off balances” from everyday life and to that effect, it actually de-frames and shakes up the quotidian. (Guattari cited by Salter in Waelder 2014)

By volume of wood, the giant sequoia is the largest tree in the world (National Park Service 2007). Native to the Sierra Nevada region of the United States, this species of tree was first discovered in the 1830s and, because of its enormous size, attracted admirers and loggers alike (Ibid.). There is a substantial history surrounding the conflict between these two groups and the subsequent legislation passed on September 25, 1890, which designated the Sierra Nevada region a protected national park (Ibid.). In the last decade, on average, one million tourists annually have visited the Sequoia National Forest to view the giant sequoias, particularly the largest tree in the park, General Sherman (National Park Service 2016).

The audiovisual installation Cathedral, created from the field recordings captured in the Sequoia National Forest in July 2014, is a response to this environment and constructed space. The initial research that informed the making of this non-linear installation occurred, however, before the three-week field recording and emerged from a previous collaboration with Andrew Denton, Aspects of Trees (2013). A key instance from Aspects of Trees is the closing section of this work, which contains a single video reassembled into nine panels (Fig. 11). Denton applied a random offset effect that altered the playback speed of each panel, resulting in a slight temporal shift (Denton 2015). The resulting visual patterns appealed to my “musician’s eye” as resembling polyphony. My immediate response was to develop a non-linear system where the visual elements could continuously transform. Rather than locking off pre-rendered visuals, as is the case with Denton’s version, my research set about configuring a non-linear method where the visual patterns could continuously alter and, in turn, affect the sonic layers.

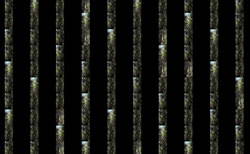

At the time of the Sequoia National Forest field recording, I had constructed a number of non-linear multi-panel patches that incorporated computer vision techniques (Fig. 12). When reviewing Denton’s Sequoia National Forest footage, I was drawn to those items that captured the shafts of sunlight through the trees as well as those that contained lens flares, which motivated my decision to use this footage in an expanded version of what I had come to call “video fabrics” (Figs. 13–14).

Constructed in Max 7, these fabrics are made by routing six identical videos onto a 10 x 10 grid (100 screens). Each video is individually coded for continuous playback at random ramp speeds between 0.85–1.15, which is governed by the sunlight computer vision analysis. These varying speeds create slight temporal shifts in the matrix and result in the “video fabric” effect. In total, 40 videos are used for concurrent playback and randomized so as to never repeat in the same order. Accompanying the “video fabrics” is a centrepiece made up of two 52-inch monitors (Fig. 15) displaying a high-resolution close-up video of General Sherman’s bark, which continuously pans upward. This endless upward motion occurs as two similar videos fade between one another.

For the sonic aspect of Cathedral, a large portion of the field recordings from the Sequoia National Park contains tourists speaking different dialects and languages. Each language and speaker has different rhythms, timbres and pitches that, in the natural reverb of this forest, overlap into a polyphonic sonic element. After constructing the “video fabric” system, including the computer vision, and after the title of Cathedral emerged, I became interested in bringing these voices into this non-linear installation without overtly focusing on the specificities of the spoken words. The process of auto-convolution — that is, convolved with itself (Truax n.d.) — seemed a suitable compositional technique with which to achieve this aim. Consequently, these text-based files doubled in length, but rather than sounding as if time-stretched, the strong frequencies became stronger while the weaker ones faded. Applying auto-convolution again to the resulting files strengthened those frequencies, and what emerged were small melodic motifs.

I was pleasantly surprised with the results of auto-convolution applied to text-based recordings, as this was not a technique I had previously explored to such a degree. Accordingly, a series of short melodic motifs emerged that in turn influenced my choice to use the singing voice and I proceeded to record a series of improvisations while immersed in the Cathedral system — the “video fabric” and sonic layers. For these improvisations, I constructed a real-time convolution instrument for recording my voice. Using the HISSTools Impulse Response Toolbox, this “cathedral instrument” contains five impulse responses extracted from the field recordings, which contain the natural reverb of the forest. During these improvisation sessions, the capacity to switch between these impulses was available. In addition, the “cathedral instrument” contains a delay system set to the first eight numbers of the Sequoia seedling cone ratio of 3:5 (Campbell 2013).

Auto-convolution was also applied to raw field recordings containing machine sounds such as the bus, human movement such as the sound of running children’s flip-flops, and bird songs. Thus the Cathedral installation contains a large folder of audio files: raw field recordings and auto-convolved, text-based and vocal improvisations, all of which are randomly triggered by the computer vision analysis based on the burst of sunlight through the trees. In this way, the captured sunlight footage runs the whole installation and becomes a co-creative and performative agent. The final sonic apparatus incorporated in this work was a poly~ poly buffer sampler. With this device, the selected audio is routed to a MIDI pitch sampler, randomly triggered by the incoming video analysis. For this instrument, I selected four vocal improvisations, two camera samples, one bus sound, one crow and a footstep sample (Video 5).

All of these sonic, visual and experiential elements fed into “an associated milieu of the emergent relation[s]” that made up the co-creative forces informing the work. Restating Manning and Massumi, these emergent relations constitute an “environmental mode of awareness”, which “does not yet seek to distinguish between human and nonhuman, subject and object, emphasizing instead an immediacy of mutual action…” (Manning and Massumi 2014, location 157).

“Alongly” Integrated

Timothy Ingold’s description of wayfaring as a meshwork of alongly interwoven narratives provides a way to orient the conditions, influences and knowledges — past and present — from which my creative research emerges (Ingold 2007, 89). Ingold equates the movement of the wayfarer — both human and nonhuman — with life that is lived along interwoven lines rather than one that goes from point A to B. The result of the movement and the subsequent lines create an ever-evolving meshwork in which each wayfarer is embedded (Ibid., 116). By examining life like this, Ingold recasts the linear orientation of past and present time to that of an interwoven narrative where the ways of inhabitant knowledge are “alongly integrated” (Ibid., 89).

What I encounter in my creative research is similar to wayfaring, as a “movement of self-renewal or becoming” (Ibid., 116). Each project has influences and narratives that progress in moments of emergence, from which the non-linear installations evolve. These moments traverse many interwoven lines, creating an ever-evolving meshwork in which the practitioner (the Wayfarer) and the practice are embedded.

The creative act and resulting artifacts become a multilayered intra-action between people, places and things. My artistic focus has shifted from a controlled (me) process to an ecology of practice, where the gesture of creativity and the artifacts that emerge are “produced by the relationship of relevance between the situation and the tools” (Stengers 2005, 185). These relationships are unpredictable and required that I adopt a more open-ended comportment to the effects and capacities available in the environments and with the materials (Bennett 2010, location 200). Consequently, I found that an æsthetic developed in my recent non-linear audiovisual installations; one that does not operate in the mainstream anthropocentric notion of creativity (Keller and Lazzarini 2017, 61) but rather emerges by intersecting with forces other than those of human design. These forces also included the “dark-depressing” and “dark-uncanny” (via Morton) out of which an alternative form of ecological awareness emerged (Manning and Massumi 2014, 157). Each installation evidences the different sensibilities, performative patterns of relationships and interwoven qualities of our material world with us in it and within it, which gives rise to different configurations in practice. My relationship to a non-linear praxis has strengthened with regard to the worth of loosening up (my) human-centric control over the final artifact, and the worth of suspending the linear trajectory of fixed media formats. I am surprised by what occurs when experiencing these works. This aligns with the position of my practice in that the move toward non-linear systems began to redeploy my relationships with the encounters in the field and in my creative research. This renewed approach constitutes a transdisciplinary dialogue where the creative practice emerges from the various strands of encounters: in the field, in the practice and in the writings and thoughts of other researchers.

Bibliography

Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2007. Kindle ed.

Bennett, Jane. “The Force of Things: Steps toward an Ecology of Matter.” Political Theory 32/3 (June 2004) pp. 347–372. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0090591703260853

_____. Vibrant Matter: A Political ecology of things. Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2010. Kindle ed.

_____. “Jane Bennett. Powers of the Hoard: Artistry and Agency in a World of Vibrant Matter.” Vimeo video (1:14:45) posted by “Vera List Center” on 24 September 2011. http://vimeo.com/29535247 [Last accessed 6 June 2016]

_____. “Systems and Things: A Materialist and an object-oriented philosopher walk into a bar…” YouTube video (1:10:09) “Jane Bennett at C21 Nonhuman Turn Conference” posted by “Center for 21st Century Studies” on 21 August 2012. http://youtu.be/pYxy-MlypUU [Last accessed 10 October 2016]

_____. “Systems and Things. On vital materialism and object-oriented philosophy.” In The Nonhuman Turn. Edited by Richard Grusin. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015, pp. 223–240.

Butler, Judith. “When Gesture Becomes Event.” YouTube video “TPP2014: Judith Butler, When gesture becomes event” (59:06) posted by “Labo LAPS” on 11 October 2014. http://youtu.be/iuAMRxSH--s [Last accessed 19 May 2016]

Campbell, Richard. “Finding Patterns in the Redwoods: It’s Easy as 1, 1, 2, 3…” 2013. Posted 27 March 2013. http://www.savetheredwoods.org/blog/wonders/finding-patterns-in-the-redwoods-its-easy-as-1-1-2-3 [Last accessed 5 September 2017]

Denton, Andrew. Private correspondence. 20 March 2015.

_____. “Cinematic Affect in a Time of Ecological Emergency.” Unpublished PhD dissertation, Monash University, 2016. Available at http://figshare.com/articles/Cinematic_affect_in_a_time_of_ecological_emergency/4719538 [Last accessed 9 April 2018]

_____. Private correspondence. 12 November 2016.

Hurlbert, Allen H., Thomas W. Anderson, Kenneth K. Sturm and Stuart H. Hurlbert. “Fish and Fish-Eating Birds at the Salton Sea: A Century of boom and bust.” Lake and Reservoir Management 23/5 (2007), pp. 469–499.

Ingold, Timothy. Lines: A Brief History. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2007.

_____. Being Alive: Essays on movement, knowledge and description. London and New York: Routledge, 2011.

Keller, Damián and Victor Lazzarini. “Ecologically Grounded Creative Practices in Ubiquitous Music.” Organised Sound 22/1 (April 2017) “Context-Based Composition,” pp. 61–72.

Manning, Erin and Brian Massumi. Thought in the Act: Passages in the ecology of experience. Minneapolis MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2014. Kindle ed.

Morton, Timothy. Ecology Without Nature: Rethinking environmental æsthetics. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

_____. The Ecological Thought. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

_____. “Thinking Ecology: The Mesh, the strange stranger and the beautiful soul.” Collapse VI (January 2010) “Urbanomic,” pp. 265–293.

_____. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and ecology after the end of the world. Minneapolis MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013. Kindle ed.

_____. Realist Magic: Objects, ontology, causality. New Metaphysics, series edited by Graham Harman and Bruno Latour. University of Michigan Library: Open Humanities Press, 2013. Available online at http://quod.lib.umich.edu/o/ohp/13106496.0001.001

_____. Dark Ecology: For a logic of future coexistence. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016. Kindle ed.

National Park Service. “The Giant Sequoia of the Sierra Nevada: Introduction.” 1975/2007. http://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/science/hartesveldt/chap1.htm [Last accessed 27 January 2017]

_____. “Statistics: Annual Park Recreation Visitation.” 2016. http://irma.nps.gov/Stats/SSRSReports/Park Specific Reports/Annual Park Recreation Visitation (1904 — Last Calendar Year)?Park=SEQU [Last accessed 5 September 2017]

Riggs, Ransom. “Strange Geographies: Bombay Beach.” 22 March 2010. http://mentalfloss.com/article/24260/strange-geographies-bombay-beach [Last accessed 20 July 2017]

Salton Sea Authority. “The Salton Sea: A Brief description of its current conditions and potential remediation projects.” 3 October 1997. http://www.sci.sdsu.edu/salton/Salton Sea Description.html [Last accessed 10 August 2016].

Stengers, Isabelle. “Introductory Notes on an Ecology of Practices.” Cultural Studies Review 11/1 (2005) “Desecration,” pp. 183–196.

Truax, Barry. “Convolution Techniques.” [n.d.] http://www.sfu.ca/~truax/Convolution Techniques.pdf [Last accessed 10 August 2016]

Waelder, Pau. “Exploring the Performative: Interview with Chris Salter.” VIDA: Art and Artificial Life International Awards, 7 January 2014. http://vida.fundaciontelefonica.com/en/2014/01/07/exploring-the-performative-interview-with-chris-salter [Last accessed 12 March 2018]

Social top