[Gallery]

Timo Kahlen

The following text is built from excerpts taken from a retrospective catalogue of the artist’s work, Timo Kahlen: Earcatcher. Selected Works / Werkauswahl 1990–2014 (Berlin: Edition Ruine der Künste, 2014), reworked for publication in eContact! 16.4.

Several of my site-specific and conceptual works are based on subversion or disturbance, explore the productive quality of intentional mistakes and glitches. Sound makes them come to life, infuses them with emotion and meaning.

Sound Sculptures

For the 8-channel sound sculpture SWARM (2008), created for the Manifesta 7 “Scenarios” exhibition, the central courtyard accessing the 19th-century Fortezza military fortress (in the Italian Alps) was blocked with a carefully positioned, powerful sound sculpture. The abstract steel sculpture — elevated slightly from the ground, as if floating — encloses the meandering, menacing sound of a swarm of bees. Initially a calm buzzing, the transient, carefully manipulated sounds become increasingly agitated, nervous and defensive as the viewer proceeds on his way into the fortress. As if striking out at the visitor, the harsh sounds are accompanied by a strong vibration of the plated, steel “beehive” defending its territory — only later to repose to a soft and tranquil hum. About the installation, journalist Aoife Rosenmeyer wrote:

Few works in Fortezza have a physical presence, but SWARM is just the opposite. On the outside, it is a large, aggressive, steel box that echoes its military surroundings. On the inside, it houses the sound of an elusive swarm of bees, at times stirring angrily, at other times scarcely perceptible; a fresh interpretation of conflict and warfare. (Aoife Rosenmeyer, “Manifesta 7: Eight Artists Not to Miss,” Art World 7 [2008])

In the kinetic sound sculpture Dance for Insects (2010), dead insects dance, shiver and float on the membranes of loudspeakers mounted into two museum pedestals. Reanimated by low frequency sound and pulsed vibration emitted from the loudspeaker membranes, their chitinous skeletons create a light, clicking noise as they touch the speakers. Caught in an endless series of random and nervous movement, the isolated insects, moved by sound and vibration, seem to be rather alive than dead. The kinetic work, both disturbing and poetic, was presented — amongst other venues — in the retrospective exhibition “Sound Art: Sound as a Medium of Art” at ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe in 2012–13. Visitors reacted strongly to the work that, as Tomasz Wendland, curator of the 2012 Biennale Mediations “The Unknown” in Poznań (Poland), where the work was subsequently displayed, put it, seems “to shift the thin line between life and death.”

Interactive Works

Signal-To-Noise (2011) relates to the history of recording media, to the vinyl LP. An analogue object, covered with scratches, with dirt and sound, is seen rotating in space. This interactive sound art work investigates the role and potential of the unintentional mistake — the deviation from the technical norm — in the process of recording and playing back acoustic signals. What can be heard, as the viewer generates multiple layers of sound from invisible interfaces hidden beneath the projection of the scratched and ruptured rotating surface, is a grinding, dirty, dusty static noise, which leaves little room for the desired acoustic signal itself. The unbalanced signal-to-noise-ratio of what is expected and what is recorded is the work’s main principle of design.

In a series of interactive works published online since 2005, I have saturated visual projections with multiple hidden layers of sound. In a live and variable process, the viewer generates his own composition of noise and beauty: a composition of buzzing, rustling, whirring, creaking and clicking layers of residue sound and vibration as the computer mouse rolls over, pauses or clicks at hidden and static and moving interfaces and buttons embedded in the surface of the work. The interactive works develop individually, are generated — always different — as the viewer moves across, pauses or clicks at the responsive texture of the sound objects.

In Undo/Delete (2011), the viewer’s cursor meanders across a white void, an empty page. His movements generate minimal visual marks and acoustic incidents, that seem to avoid, to flee the presence of the cursor — as can be inferred from the sound of ripping, crumbling, revising, tearing and deleting of information and archived data hidden on the blank page, invisible to the eye.

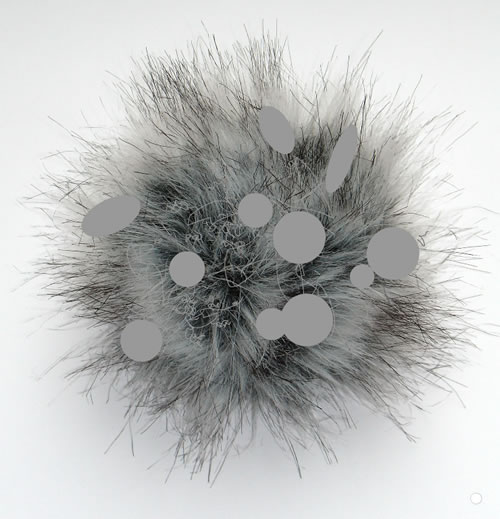

The interactive sound art work Audio Dust (2011) is about the beauty of noise. The work is based on the image of an object made of fur, a soft, tactile part of the microphone, generally used to protect the microphone from wind in the recording process.

Windjammer, poodle or dead cat: the jargon of sound engineers has many names for the wind shield made of long-haired fur that makes it possible to record sound with the microphone even under extreme wind conditions. Timo Kahlen takes the image of filtering sound as the starting point for his interactive sound work. The work makes audible all the incidental and interfering noises that a wind shield usually absorbs. Our attention shifts from the microphone to the acoustic “dust” caught in the thicket of fur. (Julia Gerlach, ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, 2012–13 for the exhibition “Sound Art: Sound as a Medium of Art”)

With references to Futurist composer Luigi Russolo’s Intonarumori and to Pierre Schaeffer’s musique concrète, Audio Dust is in many ways yet another “psycho-acoustical trap for the senses” (Werner Ennokeit, Berlin 2010), tempting the viewer to virtually stroke the warm, soft, “vibrating” object enclosing multiple and complex layers of sound.

A vanitas-like image of a ripe yellow fruit (a quince), showing first signs of deterioration, decomposition and mould, is at the base of Carpe Diem (2011). The soft, fragile surface of the object embeds particles of what seems to be organic noise and vibration, activated by the viewer as he moves his cursor across the responsive, interactive texture of the projection.

The kinetic sound sculpture Eins (2005), nominated for the 2006 German Sound Art Prize, is part of a series of sensual, softly purring, vibrating sound sculptures, and is made of artificial fur, feathers, enclosed loudspeakers and sound.

A soft, oval fur object, in different shades of grey and with a dark streak along its ridge, is placed on a white pedestal. Be careful! It’s a “trap” for our senses, taking our emotions hostage and muffling all our rational thought. Approaching the object, you hear the soft, pulsing purr, feel the slight vibration and warmth with your hands and will eventually begin to stroke the object. You just have to. We feel, what our senses believe to know. And yet: It is not the warmth of a living body, rather the heat created by the friction of the mechanical parts enclosed; not genuine fur, rather a synthetic imitation of its properties; not skin and bones that can be felt beneath the soft surface; and not a curled-in, comfortly [sic] purring cat. Instead, it is a kinetic object, formally reduced to the æsthetic shape of an ovoid, that turns out to be a precise technical machine: made of synthetic fur, of low frequency and infrasound pulsation, of two subwoofers stitched into a soft filling, of various cables, an amplifier and the source of its sound. (Werner Ennokeit, “Noise and Beauty,” in Timo Kahlen: Noise & Beauty. 25 Years of Media Art (Berlin: Edition Ruine der Künste, 2010)

Ephemeral Phenomena and Processes

My work is based on a “subtle perception of the natural and technical world” (Jule Reuter, Berlin, 2001). While at first impression they often assume (or even feign) a narrative, playful lightness — allowing references to familiar, everyday experiences and situations —, the formal and conceptual contrasts and tensions created by the works refer to a set of higher, existential questions imposed. By focussing on the small things, on seemingly insignificant and ephemeral phenomena and processes, which are commonly neglected in everyday experience, I believe my works succeed in confronting the wider issues of our times. At the same time, they are characterized by a rigorous formal reduction and clarity. I aim to create works that have been purged of all unnecessary elements, reduced to their essential core. This is most apparent in my most recent installation, DRONES (New Delhi, 2014), which consists of nothing but a bicycle with a shopping bag hanging from its handlebar. Yet this bag is filled: with the dark humming, nervously whirring and buzzing sounds of a swarm of bees — and of high-end technological, possibly military, electronic drones. A nomadic, emotionally charged, disturbing sound object transferring from A to B both potential and threat.

Social top