Interview with Laurie Spiegel

Regalia of Rodents; Afflictions of Ants; Deceptively Simple, or Simply Deceptive?

Kalvos & Damian’s New Music Bazaar, Show #134–136, 13, 20 and 27 December 1997. Kalvos & Damian on the road in New York City at the composer’s loft. Listen to the interview from the original broadcast: Audio Part 1 [0:40:39–1:42:53] / Audio Part 2 [0:36:04–1:29:25] / Audio Part 3 [0:40:20–0:56:52].

Composer Laurie Spiegel is also a computer programmer, software designer and visual artist. She is known widely for her pioneering work with several early electronic and computer music systems. Her focus with them has been largely on interactive software musical instruments that use algorithmic logic as a supplement to human abilities, and on the æsthetics of musical structure. Her best known work includes that with the GROOVE Hybrid System at Bell Telephone Laboratories, the early online transmission of digital music, and Music Mouse — An Intelligent Musical Instrument for Mac, Amiga and Atari computers. She lives and works in New York, and has taught at Cooper Union and NYU, where she founded the computer music studio in 1981. In addition to technology-based composing, Spiegel does traditional pencil composing for “old” instruments, video, photography and drawing. Her music and various papers she has authored are available on her website.

http://retiary.org

Part 1

Audio Part 1 [0:40:39–1:42:53]

[Kalvos] Here at Aesthetic Engineering [in New York City], our guest today on the show…

[Laurie Spiegel] In Laurie’s loft, is more like it…

[K] Yes, in Laurie’s loft, is Laurie Spiegel.

[LS] My father was in love with radios the same way people were with computers when they were the new technology, since he was born in 1906. He built lots of radios for lots of people. My first electronics project from him, when I was maybe nine or ten, was building a crystal radio. Yeah, that comes from him, 1920s kind of a…

[K] So we all built crystal radios. You built a crystal radio?

[Damian] I did indeed.

[K] Yes, so did I. I had connected my crystal radio to the light socket, causing some unusual problems at one point, but getting radio Moscow.

[LS] Wow! I just used the radiator. And you?

[D] I believe I connected it to small animals. I didn’t get very good reception, but I got a great response from the animals. [Pause] That’s about all.

[K] [Laughter] Our guest today, is Laurie Spiegel. So you’ve been composing for a really long time.

[LS] I was composing for a long, long time and, you know, it goes without saying that now I’m decomposing, but… is there a followup question to that? That’s a yes or no question.

[K] Well, yeah, sure it is. But you were a lutenist for a while? Still are?

[LS] No, no. Well the thing is, once you get out of practice on it… and it takes so long to get it in tune that by the time it’s in tune again, all of your interest for starting to practice has kind of gone by the wayside along with your free time for doing so. So you have to really plan ahead several days. Of course I played other instruments before the lute. Guitar I still attempt to play once in a while, but since I’m totally out of practice and don’t have my callouses, I usually get carried away the first time and then I end up getting blisters on all my fingers and they hurt too much, and then I can’t play again for a while. So that breaks the impetus too. Keyboards, on the other hand, you don’t need callouses, and they stay in tune relatively well compared to lutes. So I do still sometimes play keyboards even though I was much better at plucked instruments. I started keyboards very late.

[K] Okay, we have played your music on the air a lot so far. We’ve played most of Unseen Worlds and a piece here and a piece there. We’ve played Cavis Muris, and we’ve even played things from The Expanding Universe, which were the first things we played on the air, from 20 years ago. So how does, here’s the question you’ve been asked a thousand times, how does somebody who played plucked instruments and probably a great deal of traditional music, and spent some time in the English countryside and such, end up doing engineering, computer programming and composition, using masses of electronics. Here in your studio, we’re surrounded by electronics of every generation, from the time we were all little sprouts…

[LS] And we have a Baroque lute, a sitar, Clementi square piano built around 1810, and a whole bunch of other stuff. A dulcimer and a mandolin, which was my first instrument. My grandmother from Lithuania played it, and gave me one when I was about the same age as when I did the crystal radio thing. Some bongos, and the odd thing is that despite the number of different systems, computers (there’s about an even distribution of musical instruments and computers in this place), just about every one of them is one that I’ve had a long, intense involvement with, they’re not just here because I collect them or something. But there sure are a lot of them, and each one of them is like a whole different bunch of stories, probably.

[K] But how did you start? How did you end up at Bell Labs, for example? How did you begin using those media to create your music?

[LS] Well, at that point I had already been working for several years with analog stuff like the Buchla modular… One of the other people working in the Buchla studio — which was NYU composers workshop, which was what was left of Morton Subotnick’s old Bleecker Street studio… [that] is where I first saw a synthesizer…

[K] Did it captivate you instantly? Is that how you got into it?

[LS] Yeah, it pretty much did. I was at that time studying at Juilliard, where they didn’t even acknowledge that there was any possibility of electronic music. And writing things that of course, that I never [got to hear played], you know. And it was just awesome working with the real sounds. It was more like working as a painter, because you’re working on an actual work, or a writer, where you’re working on the thing which will be the experience that someone will have, that you can experience it. You can hear the sound. With scores, of course, it’s a mind game, it’s all in your imagination. And I really did kind of fall in love with them. But anyway, I had gotten to the point where I was just really fed up by the lack of control, lack of replicability, that you couldn’t get a patch back exactly the same and continue working on it. Editing techniques were extremely crude and limited to tape-splicing.

[K] Right, well, to sort of back up for some of the listeners, that when you say “replicability,” when you turn these older synthesizers on, everything affected them. Temperature, humidity, it seemed like time of day. And the question of whether it was going to be in tune.

[LS] The Electrocomp Synthesizer was the first synthesizer I actually owned. When the refrigerator would cycle on, it would drop roughly half the oscillators probably 3/8 to a semitone, and then they’d go back when the refrigerator cycled off. And we had a five-room apartment on a 15 Amp fuse. But that was a relatively minor thing, obviously I unplugged the refrigerator when I was recording and plugged it back in after. The simplicity of the control logic was frustrating after a while, and in 1971… okay, I’ve always been somewhat active in various visual arts, and there was a place called The Kitchen that was at that point just a video centre, and did some theatrical stuff. And Rhys Chatham, we basically learned the Buchla together. Rhys is an old friend, in fact. We sort of almost semi-agree it’s like a brother and sister relationship even though we haven’t seen each other for eons. He stayed in this loft for a few months at one point. A lot of people have lived here at various periods. [Laughter]

Anyway, Rhys Chatham decided to start an informal concert series at The Kitchen, where composers would basically be able to play works in progress and things like that for each other, and have a dialogue among composers in a performance context. In order to launch the thing, he invited his best friends to come and do some concerts. I had stuff in two out of the first four concerts, and [playing in other people’s pieces in] one of the other two. One of the first four concerts was Max Matthews and Emmanuel Ghent doing some stuff that knocked me out, because they were using computer-controlled analog synthesis with the GROOVE [Generating Realtime Operations On Voltage-controlled Equipment] system. So, eventually working up all my guts, I called up Manny and asked if I could study with him, because I wanted to learn this. He said he didn’t take students, and we worked out that I’d sort of be like his apprentice and help him with this and that. So that worked out, and so I went out as Manny’s kind-of apprentice/assistant for three months, you know, reading over Fortran listings and helping trying to figure how to debug them and how everything got patched and stuff, the lay of the land, the computer technology.

Then, Max, after about three months, kind of asked me a couple technical questions about how would you go about doing this and that, and it felt like, “Ooh, I’m being [surreptitiously] tested,” But anyway, he issued me my clearance and my badge and all that stuff, so then I had official resident position status, which I continued to have throughout the 70s. I did a fair amount of work in computer graphics and computer video as well as the music stuff. That’s how that transition happened.

How things happened is always pretty serendipitous, I think. I got into all of that in the first place because — having been basically initially a folk instrument musician, playing plucked instruments, and at a certain point when I was going crazy for various reasons and then dropped out of college and wasn’t really doing anything gratifying — I just felt like my guitar playing was in a complete rut. So I decided to teach myself to read notes, and to try to transcribe all the Bach inventions for guitar. I started doing a lot of transcriptions and learned notes. Then, when I was studying in England, I studied classical guitar with Jack Duarte in London. Well, I was there to study other things. I was really an intellectual, I still am an intellectual. I did a one-year residence thing at Oxford University, and was being extremely abstract and philosophical. I discovered when I talked about Aristoxenos (1) and things like that, people kind of weren’t that interested, but if I just sat in the corner and played guitar, they kind of liked it. So that sort of began winning out. […]

I literally was one of these people who would carry a banjo on a peace march, you know. […] I liked a lot of the southern mountain modal clawhammer-style stuff, sawmill tuning, real old-time ballads, I liked blues a lot that I heard from Chicago. I heard a lot of wonderful blues playing. Played a little, not that well. I love John Fahey’s music, that was a big influence on me. Anyway, digressing there but basically my teacher in London — I went to study guitar with him on the weekends, commuting out to London from Oxford, and I had begun writing down some of my improvisations just so that I wouldn’t forget them —, and he pointed out to me that that was called “composing,” which is not a word I would have ever dreamed of applying to myself for anything I might ever do. But he said that I should consider taking it seriously, practicing every day and writing music every day, and if I threw it away, that was fine. Just get the practice writing and do it.

So I started writing. Then he started teaching me more theory and counterpoint and stuff like that. And somehow, after my first year in New York (which was pretty horrendous) I decided to just give myself a year to see how far I could get into music, because I really loved it, and I ended up succeeding. At the end of that year, I was teaching music at a community college. I was working pretty steadily doing soundtrack work. I had music students and stuff like that, and I was functioning professionally, whereas the first year I was in New York, I could not get any work that didn’t start with “How fast do you type?”

And I mean, coming in from Oxford University to “How fast can you type,” is rather a downer. I had even gone to IBM to apply to their computer programming training school, because it just seemed interesting and because I’d always been interested in science and math and liked them. And they told me — and I think this is probably utterly sexist, because I turned out to be an okay programmer — that I had absolutely not any aptitude for working with computer technology. I think it must have just been sexual stereotyping. Either that, or they looked at my Social Science degree and said…

[K] Well that was suspicious anyhow.

[LS] It wasn’t hard science, yeah.

[K] Do you have any music recordings from those early days?

[LS] Yeah, I have a lot of recordings. I don’t know what state they’re in.

[K] Well, let’s hear something of that early music.

[Ed.: Laurie’s History of Music in One Movement was to be played but a copy was not available at the time of the broadcast.]

We listen to Cavis Muris,I by Laurie Spiegel, followed by remarks from K&D [0:58:30–1:04:05]. Interview resumes at 1:05:35.

[LS] This is my History of Music in One Movement, for solo piano, although I first publicly performed it on an Apple II computer.

[K] [Laughter] Okay, we get away from the acoustic immediately.

[LS] Well, it is a piano piece, and it goes through all the historical styles. I sort of felt like I wanted to experience being in each historical style and feeling internally the need to move forward and break out into the next style. I mean, to be in the late Baroque, wanting to move into the Classical state of mind. So I wrote that, and it was really a wonderful experience writing it, and I enjoyed it a lot.

[K] How far did you get in the history? Did you bring it right up to the…

[LS] Yeah. But of course, the piece comes with a caveat. This history does not purport to be any more objective, comprehensive or unbiased than any other history. So, obviously, I will have spent time with the Impressionists and Bartok, but I forced myself to write a couple bars of pointillist serial material for historical accuracy, but I hate those composers. [General laughter] But by and large, the rest of it flowed. It starts with just playing with the materials, and seeing what happens with the musical patterns, and things evolve. It gets gradually more and more emotional through all these cycles of what Nietzsche would call the Dionysian and Apollonian alternating, but basically the overall thrust is that it gets more and more dramatic and emotional through the late 19th century and then has a real breakdown in the 20th century. It goes off the deep end and breaks down, and that’s where you have this post-Webernite episode. [Then it retrogrades back to more musicality and leaves off sort of like where we are now —LS July 2008].

[K] You don’t care for that, is that what you’re saying?

[LS] No, that was stuffed down our throats and force-fed to us when I was studying composition, and it was just not my thing. It just has a lot of bad vibes because of the pressure that was brought to bear, and the judgmental attitudes of many people.

[K] That is not the first time we’ve heard composers on the show that say that.

[LS] Well, at this point in history it’s easy to say that, because it’s not the same atmosphere it was in the early 70s. I mean, I was studying at Juilliard from 1969 to 1972 and it was, I mean, the things I had in common between my electronic music I was doing secretly downtown (that couldn’t be brought into Juilliard [laughter], on the Buchla) and the stuff I would play at The Kitchen and stuff in my off-hours, versus the lute music… early and renaissance music not having really begun to become a major staple of the known recorded and concertized repertoire… I mean, I got a very good background in general at Juilliard in many ways, but the particular things that I was into were kind of all outsider things. Also, during that period I was steadily doing soundtrack work, I was a staff composer for a small educational film and filmstrip company [and that had to be real direct music, not abstract intellectual pattern manipulation —LS July 2008].

[K] Now, wait! How did you get that job? I mean, how do get a gig like that?

[LS] Well, actually Frederic Rzewski gave it to me, because he didn’t want it anymore, and then I got some work from a very good friend for a long time, Mike Sahl, who got me into music editing in the late 70s. I did a lot of that kind of cutting room stuff. But Juilliard had this attitude that redundancy should be limited for music, whereas I felt, having studied lots of kinds of psychology as an undergraduate and everything else just intuitively, that redundancy is one of the most essential components of music. And in fact, perceived redundancy is an essential component to æsthetic experience in the temporal domain, I think. Boulez was a very dominant force in the 70s in New York, obviously, because he was here… I always felt that was, in terms of just playing cognitive psychology totally in our face. I didn’t enjoy it, that’s just my personal taste. I know a lot of other people do, but when I wanted to put something on the record player, just to listen to a piece of music, it just was never Boulez or Webern.

[K] In other words, you’re saying that people have to hear something a couple of times to understand, and to feel, to sense out? What do you mean by redundancy?

[LS] One way of achieving redundancy is to play the same piece over and over, which is how it is that when a person listens to a serial piece that prohibits redundancy they eventually come to appreciate it, because they begin to be able to predict everything because they’ve heard it a whole bunch of times. Music is, for one thing, the manipulation of human expectation, to create emotion. It’s many other things besides that, but that’s one of the primary things that it allows an artist to do, is to deal with human emotion by manipulation levels of expectation, disappointment, gratification. I mean, look at all of the great forms and processes from history: Fugue, Rondo, Sonata, Canon, Passacaglia. Repetition is an inherent component of structure in most of the dominant forms. Even the normal strophic form of song.

I personally felt that added to that could be the extrapolative method: you didn’t have to use redundancy to structure a piece of music, but you had to have something which would allow the mind to be able to feel for what would come next, so that what happened next would relate to that in a meaningful way, as being different or same, or moving into a new light, or all of the different emotional things that can happen moment to moment in music.

That can be done either through repetition through variation and alteration, or it can be done through extrapolation, in that trends in sonic data which tend to continue in certain directions are likely to continue to continue. So that, for example, if you’re making a crescendo, and you’re adding temporal density during the crescendo, you can create an emotional climax within that crescendo by building the timbre along with the amplitude, and then at a certain point, taking the timbral thing down until it’s very thin again, while the amplitude and the range continue to expand, and then bring the timbral stuff back up again. That can be more powerful than keeping them all in sync. And that can only happen because the mind is expecting continuity, and then it feels something, emotionally, when that one component goes against the grain of the rest of the continuities, and then returns to it. Kind of like an off-beat method of music theory, but that’s sort of the kind of way I tend to think.

[K] Okay, well I think one of the things that keep cycling around in my own questions about how people compose, is how much do you think your audience can hear? You say that, okay, the question of redundancy comes up, but you give us an illustration of a change of timbre versus a change of dynamic…

[LS] That was actually an illustration of extrapolation, rather than redundancy.

[K] But regardless of what it’s an illustration of, your suggestion that it’s more hearable or more… what are you trying to get at by saying that? That the serialists are not memorable?

[LS] What I’m trying to get at is feelings. What I’m trying to get at is the fact that there’s a tremendous amount of not-verbally-articulable emotion we each have internally in isolation that in fact we share — and that music is a way of making tangibly common that which we’ve been very isolated in, that we get something out of that. Make part of the common public human vocabulary of acknowledged experiences, stuff that’s virtually inarticulable, that has to do with how we feel about our experience of being alive, that we really do have in common, but don’t have enough of a way to find in common. That’s really sort of the bottom line. But how I get to the other stuff, the structural stuff, is really just listening.

I think maybe if I have any advantage as a composer — and this is one of the ones that I thought was one of the biggest disadvantages (which would turn out to be probably a great strength) — was that I started out listening to music a lot and playing by ear without notation, and particularly not conceiving of myself as someone who might ever go into music until my early 20s.

We listen to Three Sonic Spaces, III by Laurie Spiegel [1:17:17–1:23:00].

So that what I liked and what I felt about music, my values and my tastes, was all pretty much together before I set about learning the techniques of writing and composing in any structured way, and before I really had a head-on encounter with the way various types of established music theory conceptualized musical structure and material. So I had a lot of stuff worked out in my head, and I particularly had my values worked out from a listener’s perspective. This is completely different from the shock of discovering where all the rest of the kids at Juilliard mostly come from, where they’ve all been reading notes since before they could read letters of the alphabet. They have never really experienced music without it fitting into this notational and conceptual language. They’ve never experienced it without that intervening in their mind as a filter between them and just the sensual experience. Most of them also had, from the beginning, their identities and ego tied up with their involvement such that they would tend to favour things that they did best, rather than things that they just enjoyed most hearing, or things that they get the most praise for or whatever. There all kinds of non-musical factors in how you grow up being a child prodigy that I didn’t go through, growing up being a listener who never expected to go into music, but just loved it.

[K] So take us to how you use — if I can phrase it this way — “the machines”?

[LS] Hmm… are you sure it’s not that they’re using me?

[K] Okay, either way! [Laughter] How is the music coming out? You make a point of this strong emotional component, the strong affective sense, yet… you sit in this incredible studio and work with a panoply of wires and screens.

[LS] This is nothing compared to the early days. I showed you earlier the prototype 48K Apple II with the 8080A breadboard computer sitting on top of it, with an audio patchbay that I built coming out with a whole bunch of capacitors, resistors and potentiometers, sticking into this breadboard, that I used to perform on? [Laughter] God, you know, times have changed.

It’s a complicated process, but I really try to use real-time interactive methods of creating and controlling sound, that I can relate to on a physical as well as an intellectual level. In order to do that, I have to spend months or years programming and writing software based on my own analysis of the kinds of control I want, and refining that. I also have to figure out what can be automated, which is anything that I know how I would do something in a given situation, I should automate in order to be clearer, to be able to focus [better on the parts of the music-making process that can’t be automated, to get any mechanical stuff to out out of the way of the art part — LS July 2008].

[K] Give me an example of what that would be.

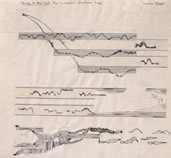

[LS] One of the first things that I did that could be totally automated, was in The Expanding Universe. You’ll hear it, it’s a little algorithm that simply puts notes on whichever speaker has the fewest notes sounding, so that overall there’s a stereo balance maintained and you don’t end up with all the voices being on this channel instead of that one. That’s really the kind of thing I can do without thinking about while I’m actually making the music, and it can do a better job than I probably could, and it’s not that important. There are other cases where I want to do pans by hand, such as in Passage, where I did all of those variable faders by hand, all of these long lines of ups and downs and crossways. There are certain aspects, for example in my program Music Mouse, of harmony that can be easily automated. You can track something with doublings very, very simply: “double at x interval,” the 3rd, the 5th, the 10th, whatever, and go major/minor, this or that. Then, beyond that with Music Mouse, or all the other variations you can switch in and out of, parallel or contrary motion. The harmony gets a little dicier in contrary, obviously, especially in two voices both going contrary. You could introduce a rhythmic component and have them voice themselves, but a lot of this stuff can be done. Each piece, with its own piece of generative software, brings up different problems, and in each piece I want to reserve different variables for my real-time control.

But some of the variables I began working with from the very beginning were what you would consider very high level, abstract ones. I mean, if you’re playing an instrument, you are physically controlling, and have to control, the timbre and articulation of every single pitch, as well as selecting which pitch and when. With computer logic, you can work with parameters such as the rate of change itself, which maybe in the Baroque people might recognize as the concept of harmonic rhythm. I wrote a basso continuo generator once, actually, that had as one of its variables the change in harmonic rhythm, in various ways. I wrote that for a friend for one concert. But this is something that we verged on touching on a number of points, which is information theory, which is a big thing at Bell Labs, and it’s a big thing for me.

Okay, in communication theory, à la Shannon, information theory, you have a communications channel, an encoder and decoder, and noise. And for different kinds of noise and different situations, you have to figure out what kind of signal is going to get through the best. And Shannon basically reduced that to a science. He came up with formulas for finding the optimal mix of that which is predictable (redundancy), and that which is not predictable, which is the unexpected, which is information. Something that tells you what you really did not know before and couldn’t have predicted is information. And [to compensate] for different kinds of noise, of course you have different levels of various variables, there’s speed, amplitude, repetition, patterns, the lengths of the patterns which may be repeated. For example, some of these spacecraft that have gone further and further out, such as the Voyagers, my understanding is that they will repeat each time, and more times as they get further away and the signal gets fainter and the noise is higher, and that way you’re more likely to be able to accurately reconstruct the data it’s sending. So that in the beginning, it maybe only repeats something a couple of times, but after it gets way out there it might repeat something many times to make sure that it gets through.

John Pierce, who was at Bell Labs, and was a really brilliant person, wrote a book based on Shannon’s work, where he also spent some time dealing with the application of information theory to musical structure, looking at different types of music as having different amounts of redundancy. Of course, the theory doesn’t deal with meaning, just information. But you can see in different styles and different types of music that there are different balances of redundancy and new unpredictable information, and in fact, that toward a climax, generally you have more new information, less predictability, and tension heightens, and then there’s a resolution to something which becomes essentially new [or which confirms a prediction the listener has formed in their mind, such as a cadence to the tonic, and there is an emotional reaction to how what happens relates to their expectation — LS July 2008]. You can structure curves of musical or emotional drama out of changes in informational entropy. (2)

You can program a computer — and this is the kind of stuff I was into at Bell Labs in the 70s — where you can have a variable that will control something like informational entropy, and have all the notes and stuff being generated, but having whatever variables you wish (in terms of, you know, timing, pitch content, appoggiatura) responsive to high level variables that let you control the essential moment-to-moment predictability of the material, and then, because you’re dealing with a very small number of very powerful variables instead of a large number of weak ones, you have hands and mind free to also accompany that with real-time input in the timbral domain. For example, I used to use a three-dimensional joystick to control envelope decay length, the amount of reverb mix, and filter cutoff for lowpass filters, in real-time with one hand, while playing probabilistic- or entropy-based variables and various kinds of things like that with the other hand on knobs.

We listen to the end of part I of The Expanding Universe, by Laurie Spiegel [1:35:20–1:37:00] and Riding the Storm [1:38:32–1:42:53].

Part 2

Audio Part 2 [0:36:04–1:29:25]

[LS] So the thing is to take something which may take a great deal of forethought in structuring an interactive system, so that you get as much musical oomph out of it as you really want, and control as much stuff as you possibly can. You want to be able to control a whole orchestra in real-time in the moment and have it be meaningful. There’s a great deal of preparation in that, and then you get to a point where you are actually playing the thing. Then, of course, you always run up to its limits, and you change it and you run up against its limits, and you don’t like the way this is coming out and you change it, and it’s a constant learning experience where you learn more about yourself. It’s a synergistic process that goes back and forth between composing and writing software.

[K] The number of questions this generates is enormous [Laughter]. I don’t know how I can ask…

[LS] Okay, well, end of statement.

[K] Somehow I’d like to ask that…

[LS] Maybe you should just play some music and let them think about it.

[K] Well… [Pause] but, one of the questions is, if you take… I don’t know how to ask this so that you can answer it in less than, you know, half a day, but if you take an information theory analysis of Mozart, don’t you get a different result if you analyze it after it’s been listened to a few times? And how does that change the emotional content, because it becomes more predictable because you know it…

[LS] You get a different result æsthetically as a listener, but if you analyze it as an information structure, it’s the same data.

[K] But you talk about emotional impact in terms of predictability and redundancy, and using those sorts of terms. If we get more familiar with a piece of music, and you…

[LS] Well, the funny thing about music, and I don’t really understand it, but it doesn’t matter how many times I’ve listened to a piece of music I love, I still feel it. So I think perhaps, the feeling level of this does not get jaded with memory. I mean, there are pieces we all know that we’ve once loved and are now bored by, but there are many pieces that seem to stand up extremely well, and that’s one of the tests of good composing, and it’s one of those indefinable things that I don’t know the answer to. Almost as they say that pain itself has no memory, you remember the experience but you don’t remember the sensation? There’s some level of music which the intellect doesn’t seem to get in the way of, that we can go through the same piece and feel the same chills going down your back again, even though you know every note in that climax and you’ve studied the score.

[K] Yeah, I can point to pieces in music history that do that for me. Certainly Stravinsky’s Sacre du printemps is one of them. I’ve listen to that and it doesn’t matter how many times I get to the Dance Sacrale, I find myself caught up in the moment.

Now back to your music. You talk about both of those sets of elements, the information theory, the sort of intellectual component, and you talk about the emotional component. When I have played some of these for myself, I found myself getting involved in them, and I remember when I first talked to Damian about Laurie Spiegel’s music. I said, “You know, I’m not sure you’re going to like this stuff, because this stuff sometimes gets too pleasant.” [Laughter] “Sometimes it doesn’t have enough edge,” and yet as I listen to some of the later pieces, some of the pieces on your newer CD…

[LS] That early stuff, yeah, I have a hard time listening to it too, but there were tremendous limitations when a lot of things were very early. You’re talking about The Expanding Universe…

[K] Certainly, because that was my first encounter with your music, was The Expanding Universe.

[LS] Some kinds of music of course don’t want an edge, they just want a lyricism. But that’s a different thing. The technology was very primitive in many ways, and I wasn’t able to have anywhere near a fraction of the kind of timbral control that everybody takes for granted with digital audio and electronics these days. In terms of computer control, it was very bottlenecked as well, and I was learning everything, programming, and the whole thing was new. The interactivity was new on that level. They were also done — don’t forget, when you say “too pleasant” — at a point where the establishment really was all hard-edged blip and bleep type music, heavily Boulez-dominated. And people doing music like Phil Glass, Steve Reich and Terry Riley during that period… to work with tonal materials, modal materials, and modal rhythms was considered absolutely outlandish and radical. So there’s some historical context on them as well as the technology being utterly primitive by today’s standards.

[K] [Laughter] You hold your head…

[LS] Oh yeah, I can barely listen to this myself anymore, but maybe eventually I’ll think of them as done by another person so that I can bear to listen to them, but I don’t think I’d want to. [Pause] Yeah. Anyway, let’s talk about something else… [General laughter]

[K] Okay, let’s talk about Music Mouse. Now is apparently, and we’re in this sort of technological universe right now, where the world is divided in ways in which I can’t cross over a certain barrier to try Music Mouse, because I use a certain technology that it doesn’t run on.

[LS] That’s not true, because you’re in my loft, and therefore you can try it.

[K] Well, we have that opportunity then, good. Well first, two minutes on Music Mouse and what it is, and then we’ll go over and do it right here on the show.

[LS] Music Mouse is a program that I started writing about ten years ago when I got my first Macintosh, which was my first mouse-and-windows-interfaced type of computer experience. It occurred to me, the natural thing that’s so obvious, and nobody else does it, is that you want to be able to just shove music around with the mouse. Also, coming from my previous computer music work, I’ve used the computer very much as a musical instrument rather than just a recording and editing device, since recording and editing were really barely possible when I was working. Well, we recorded functions of time, we didn’t record music. Anyway, so I wrote this program, of course it started just with shoving the music around with the mouse, and then it needed a few constraints because of course it sounded lousy. But then it needed a few options so you could keep changing, and it just kind of developed. Then, a number of people who saw it or liked it wanted copies, I realized I had to just charge something for it or mass-produce it to some degree because it was just ridiculous [to be making copies one by one and showing each person how to use it one at a time. I needed to write a manual and do print runs and cover the cost — LS July 2008]. Then it got shown at the MacWorld Expo in Boston, I think, in January of ’86, and suddenly there were rave reviews in all of these places, and MacUser awarded it a five-mouse rating.

[K] A five-mouse rating!

[LS] Yeah, first music program to get one. (3) Anyway, then I was stuck, and that’s why I came up with the name… well, actually Keyboard Magazine came up with the name “Esthetic Engineering”. They did a profile article on me in ’86 called “Laurie Spiegel, Esthetic Engineer” that Paul Lehrman wrote, and I thought that was a nice term.

[K] It is, yeah, “Esthetic engineer,” it’s a terrific idea, yeah. Wonderful.

[LS] Yeah, well, I engineer æsthetic experiences.

[K] Yeah, really [Laughter]. Let’s move over to…

[LS] To the Mouse? Also, I should mention that there are a lot of things which have ticked me off about the way music has always been done that need no longer be. So, I was really pleased to be able to put it out, because being an instrument that requires no conventional training, the most minimal physical coordination is required. If you can move an XY pointer, you can play Music Mouse, and otherwise basically just having a good ear, and being able to be moment to moment in the sound, doing stuff. It’s possible for just about anyone to play music, and a lot of the press it’s gotten of course has to do with the fact that essentially it makes it possible for just about anyone to play music. It runs the gamut. It’s had users from three years old through famous professionals. It’s been used in not only schools, colleges and universities. Someone used it in the Philadelphia prison system, among other [prisons] that it’s been used in. It had been said that nothing that they had found held their attention like playing Music Mouse. There was nothing they’d ever come up with that could hold their attention. They got off on playing music. There also has been a controversy because, of course, the constraints that I put in it tend to reflect my own personal æsthetic preferences.

[K] Such as, what kind of complaint would you get?

[LS] The common form is that everything you do might sound a little like Laurie Spiegel’s music or, “If you like Laurie Spiegel’s music, this is a program you might want to make music with,” or at the extreme end, “This is just a Laurie Spiegel composition.” I think Mark Canter at Macromind said that in some review, that Earle Brown, John Cage, Pauline Oliveros, or other process composers would have considered it a musical composition, but Laurie just put it out and called it a program. So, it’s been confusing, because in the first year I got a letter from some guy with a band, who said, “Shouldn’t this program join the musician’s union? Because it’s up there gigging with us, it does its own material, it contributes to the group in ways that are different from anyone else. It’s a member of our group.” And there was this other guy…

[K] And did you… pay the dues?

[LS] Well, of course not. [General laughter] I don’t think people pay programs, right? Different people have come to me, total strangers from our viewpoint, who say things like, “Oh, I’m so glad to finally meet you.” They’ll come up after a lecture, “I feel that we’ve been collaborating as composers for years, I’ve used your software, and I can feel your influence in my music, and I really feel that to some extent we’ve been musical collaborators.” And these are people I’ve never met before, you know? There is a feel in the program, relating to what I was saying before, there’s a heavy bias toward continuous motion rather than jumps, in every dimension. You have to work to make things disjunct. You can do it, but the natural biases are for things to be relatively continuous, for melodies to be on the stepwise side rather than the bizarre leap side.

[K] Well, I think we should give it the Damian test.

[D] Oh, good, here we go. Where is it?

[LS] Well, it’s hiding on a disk someplace.

We listen to the conclusion of Cavis Muris [0:49:57–0:54:10], by Laurie Spiegel, followed by some personal conversation and Three Sonic Spaces, III [0:56:00–1:01:25], by Laurie Spiegel.

[D] Now there is one minor problem with your Music Mouse. I understand that this is not IBM-compatible, and our radio is IBM-compatible. We do not run Macintosh equipment, nor do we give it more than a cursory mention, ever. That being said, we will attempt to make this work on our program, but again, there may be some auditory…

[K] Listeners, please adjust your radios for Macintoshes. The setting is in the back, turn the unit around and you’ll find a little switch. You flip that switch to the ‘M’ position.

[LS] [Hands Damian a Music Mouse Keyboard Map] The radio audience can’t see this, but you might want to look at it in order to…

[D] 1988? This is a bit…

[LS] A bit dated, but they’re still in the same places. You might be able to ask questions off it or whatever, but it’s a keyboard map. I mapped the keys on the keyboard as switches and faders. So you don’t type things, but you use the keyboard as a controller. Then you play it by moving the mouse.

[K] Just an example of what those activities are, you have things such as pattern selectors and tempo selectors, breath controls and foot controls and such, that’s what you’re talking about.

[LS] Yeah, types of harmonization, diatonic, octatonic, all of those guys. We’ll mix in some stuff. [Tonal noise] Okay, there’s some stuff. So if you look at it at its simplest, you just move the mouse and it plays music. [Tonal pad sounds]

[D] This is a very reverberant mouse.

[LS] This is a variation on John Chowning’s [FM] piano sound, which I like a lot. We’re listening to a Yamaha TX rack, this sound. Have you ever crawled in underneath a grand piano to listen to it? The dog does that when I play. I used to do that, and it sounds wonderful. It sounds very reverberant. So I’m moving on the X axis there, and I can add voices on the Y axis. So you play it by just gently moving the mouse. And you can do different things with it. [Improvising] Let’s try making everybody contrary motion. I’m putting two voices on each axis. So we have two contrary moving pairs, either chromatic, or what sounds better to me actually is octatonic, which I like a lot.

[K] Can you tell our listeners what you mean by that?

[LS] The octatonic mode is used by Bartók, for example. It’s eight notes to the octave, with major and minor seconds alternating. Stravinsky uses it. Now, the harmony, of course, tries its best to be meaningful harmony. You can change sounds, with no reverb it sounds a bit harsh, but this is just to show you and give you some idea of what it is. Now, you’ll notice that I’m changing the timbre. These are faders, leaning on the left key fades it down.

[K] You’re holding down an ‘M’ or an ‘N’ key, which are acting as faders there.

[LS] Yeah. The capital letter punches it to the extreme, like maximum and minimum values, and you’ll increment and decrement [volume swells] by just holding down the keys. I have four different fader pairs here that are changing the timbre of this. [Dissonant metallic swell] You’ve heard a lot of those kinds of things in some of my music. [Improvises]

[K] I’m looking on the screen as you’re doing this. There’s a list of the activity, the phrases say “harmonic mode,” “treatment,” “transposition”.

[LS] Yeah, and you can see the QWERTY keys go across, chromatic, octatonic, mid-eastern mode, diatonic, pentatonic and quartal. Those are harmonic modes and modalities, basically, and you want to be able to change in real-time between them. They go between maximum resolution — between an equal temperament octave, chromatic at one end, to a minimum which is quartal. That is, they’re in order by a decreasing number of notes per octave resolution. So let’s go back to our little piano. This is a version of the program I don’t have out yet, and it has in it a little thing called “Why not,” that says, “Give me a new idea,” a little brainstorming thing. Okay, now here we’re in an alternative display [Pentatonic melody], and it’s put us in a transposition down and in a pentatonic mode, contrary motion with automatic pattern generation going on. Two of the voices are muted, which I can then punch in and out. [Second line being added then muted] And of course I can speed it up. [Quickly speeding up] Anyway, that gives you a basic idea. There’s nothing inherent in the program, but I seem to have gotten into another one of these MIDI feedback loops which I now have to break. Either that, or the computer crashed.

[K] Oh, they don’t do that. We know that this particular…

[LS] I don’t think so. Happens all the time, particularly in versions that aren’t released that I’m working on. This is the most recent compile.

We listen to The Hollows by Laurie Spiegel [1:11:12–1:15:43].

[K] Can we give it the Damian test next?

[LS] Yes, that’s just what I was thinking, why don’t we do that? Now, there are two displays, this is the standard display that everyone knows, where you can really see what’s going on. This is what I call a “polyphonic cursor”, and you see that these point to the notes you are playing and hearing. [Improvising melody/chords] Then, on this map — and you probably shouldn’t mess with these — are different variables. I sometimes refer to this as Trio Sonata format, because it’s an independently-moving treble line, with the bass line and two moving inner voices contrary to the bass. It tries to somehow handle the harmonies and also canon. It’ll do sequences and patterns on its own, too. [Arpeggiating sequences]

Let me reset here. Yeah, I just hit the ‘help’ key, and it put the faders for these various controls up next to the variables so you can easily see what they are. Now why don’t you sit down here, the innocent victim. Just move this very gently. [Playing notes]

[D] You made a statement earlier, that anyone who wanted to compose should be allowed to.

[LS] Anyone who wants to make music — it’s not a question of “allowed” — should be able to.

[D] We’ve had a number of guests on our show, who… their performances would dispute that statement.

[LS] [Laughter] Oh, oh…

[D] We won’t name them, but… [Improvising]

[LS] Damian performing on Music Mouse, on which he’s never played before. [Continues to give instructions to Damian while he plays on Music Mouse] So you can see how it makes it easy to make music, and you’re thinking on a compositional level. The decisions you’re making while you’re playing it are, “Do I want to go over to this kind of character?” [Tweaking more controls as Damian plays]

Yeah, it makes it ridiculously easy. I got a letter from someone, a professor at a fairly well-known musical college once, complaining that after his students had been given the software to work with, he had a hard time telling whether his students deserved the A, or whether they just did this composition using the software, and it really made it hard to evaluate people. Which basically for me, calls into question the wisdom of trying to evaluate people in music. [Laughter] But for him, it called into question this type of software, because after all, for him it was more important to be able to weed out as many undeserving, untalented people as possible, whereas for me, the goal is that everybody who wishes to express themselves with sound ought to be able to with the technology that we have these days. And it’s been making it easier for myself, not that I don’t do it the hard way still. The last piece I wrote was a more or less by-hand thing for solo French double harpsichord. [Pause while Damian plays synth sounds erratically] So I think he likes it. Did it pass the Damian test?

[D] It does, it has very mouse-like characteristics, and I do have a fondness for…

[LS] Rodents.

[D] I do.

[LS] Me too, me too, it’s good. Now, a lot of people say that it’s like me, but I’ve heard a tremendous number of things come out of this program that I would just never have done or thought of. For example, it was a knockout to me the first time I saw someone using it to control a drum machine. People were into it for rock and roll, and I cannot imagine how, but they do somehow. [Further instructing Damian] You get to play it too, you know? Questions, comments?

[D] Does it come in blue?

[LS] Mm-hmm. I wish, but it’s a grayscale monitor. Only if you play blues. He keeps hitting the “Give me a new idea” button. I mean, you can hear there’s a bias towards stepwise motion, towards fades rather than leaps in terms of all of the dimensions. [Spiegel continues to give instructions]

We listen to From a Harmonic Algorithm by Laurie Spiegel [1:26:38–1:29:25], concluding the second part of the interview.

Part 3

Audio Part 3 [0:40:20–0:56:52]

We listen to Kalvos improvising on Music Mouse, with further assistance by Laurie Spiegel (segment commented on by Kalvos and Damian, after the fact) [0:40:20–0:56:10].

[D] We’re very grateful for your coffee and hospitality and mouseness and everything connected with this particular interview, and we hope to do more in a future episode of the Kalvos & Damian New Music Sesquihour On the Road, not from Plainfield, Vermont, but New York City.

[LS] Or, “One place is as good as another in different respects.”

[D] There are many places where we have been that are not nearly as good as other places. Many of which we passed through on the train, this very day.

Notes

- Aristoxenos was among the most important ancient Greek writers on musics and music theory, yet just as few people have heard of him today as when I was a student in the 60s. He wrote over a hundred books on music, though alas all but a very few burned up in library in Alexandria. I had to have access to the Bodleian Library in Oxford to get hold of the little of his work that remains at the time and have a friend translate it from the Ancient Greek for me. I would not be surprised if the few books that survive of his are still out of print. My theory about him was that the conceptual models he used in describing music embodied a post-Aristotelian way of organizing information, except because it was limited in its application to music, it was never brought to general attention the way Aristotle's syllogisms and schemas were. [LS]

- See Laurie Spiegel, “An Information Theory Based Compositional Model,” Leonardo Music Journal Vol. 7 (January 1998, MIT Press). The Unquestioned Answer was composed with the techniques described in the article and is available on the CD accompanying the journal. http://retiary.org/ls/writings/info_theory_music.html

- Some reviews are available on Laurie’s site.

Social top