Hugh Le Caine’s Polyphonic Synthesizer

Closing the 2014 Toronto International Electroacoustic Symposium (TIES) was the Special Session “A Noisome Pestilence: An afternoon of Hugh Le Caine,” which brought together composers and researchers around Le Caine’s instruments. The session was moderated by Gayle Young on Sunday, 17 August 2014, and featured presentations by Kevin Austin, Richard Henninger, David Jaeger, Pauline Oliveros and Paul Pedersen.

I should perhaps start by just claiming to be one of the first people — or students, at least — to work in the University of Toronto Electronic Music Studio (UTEMS). That was in 1958. I was a new master’s student, just having quit medicine and gone into music. There was a studio that Arnold Walter [then Dean of the Faculty of Music at the University of Toronto] and a couple other professors had put together with a little equipment from the NRC [National Research Council] and I managed to talk my way into it. I learned how to splice tape, if nothing else.

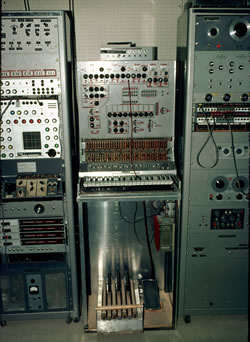

What I wanted to talk about today a little bit was the Le Caine Polyphonic Synthesizer. Unless you were fortunate enough to go into the McGill Electronic Music Studio in the early ’70s, and perhaps into the ’80s, you have never seen this instrument. (It’s on display in Ottawa at present; not functional I’m sure, but present.)

It came about in a rather peculiar way. I had gotten to know a man in Montréal by the name of Dave Wilson. Those of you who were in Montréal may remember that he ran The Audio Shop on Mountain Street. He also had a corporation called the Dayrand Corporation. He and a group of other entrepreneurs made some money during Terre des Hommes ’68 building and running the Spectrophonia Pavilion. I don’t know if any of you remember that, it was a sound and light show with two works being presented there: Berio’s Sinfonia and Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf. It had an elaborate system of measuring the frequencies and amplitudes on the 12 audio channels of the 16-channel tape. There were special recordings made by the London Symphonic Orchestra on 16-channel tape, which was the largest tape recorder — the most number of channels available — at that time. It was played back over a 12-channel sound system in the pavilion and was accompanied by a rather elaborate light show that responded to amplitude and frequency, and triggers and other control signals recorded on the remaining 4 channels of the 16-channel tape playback.

In any event, I was involved with Dave Wilson in putting together the light show for that pavilion. I introduced Dave Wilson to the Electronic Music Studio and through that to Le Caine. He got interested in Le Caine’s inventions — we had many of them at the McGill studio; just as many, I think, as at the Toronto studio. He expressed some interest in 1968, as perhaps being ready to manufacture, through Dayrand Corporation, one of Le Caine’s inventions. Le Caine had, as Gayle [Young] mentioned, asked composers periodically: “What do you want? What would you like to have and how would you like it to work?” I had mentioned to him that we have a monophonic synthesizer, we have a Moog in the studio, but it would be really neat to have a polyphonic synthesizer. He sort of liked the idea and it turned out that Dave Wilson liked the idea and so it became an active project. By the 1971–72 academic year, Le Caine delivered a polyphonic synthesizer to the McGill studio.

The middle piece of equipment in Figure 2 is the Polyphonic Synthesizer. At the bottom of the screen are a set of seven keys from an organ pedal keyboard, and an organ volume control. The pedals were used to both direct and control the voltage of signals that could be sent wherever you pleased. Those of you who ran or worked with the Moog synthesizers, you will know that they were voltage controlled and that you used control voltages of various kinds and all kinds of fancy patchings to determine the kind of sounds that you produce. This allowed the performer — this was a performance instrument — to perform in real time and change, if you like, the patching, and the level of the controls using these pedal keys with your feet. So you had to be an organist as well as a pianist to play this thing.

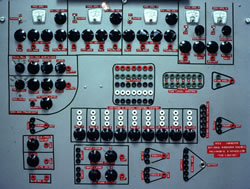

Figure 3 shows the keyboard and the step-pitch controls, the slider — one for each key. Every key had its own oscillator. The next row of sliders is the fine pitch control and the top row of sliders is the timbre control, which altered the waveform.

The devices and the patch bay of the voltage-controlled modulation section can be seen in Figure 4. There were five modulation oscillators at the top, a couple of envelope generators, a couple of filters. They could all be patched together with banana plugs at the time. Kevin, you probably remember using this, did you ever write a piece for it?

[Kevin Austin] No.

[PP] I did, I wrote one. I’m not going to go into the technical details of it [but] if you ever worked with an analogue synthesizer like a Moog or a Buchla back in the ’70s and ’80s, you’ll know how this kind of a synthesizer works, only here it can be applied in quite a sophisticated fashion to a polyphonic keyboard, each key with its own voltage-controlled oscillator for producing sound.

In 1971, Prime Minister Trudeau made a speech on “The Status of Women.” I thought it was a kind of interesting speech and managed to get some unnamed person from the CBC to give me an uncut, original version. I used that as the basis for a piece called For Margaret, Motherhood and Mendelssohn. This speech was made by Trudeau just shortly before he married Margaret Sinclair.

Obviously this is intended as a mildly facetious commentary on Trudeau’s speech. You will have noticed that this was a deconstruction, or a recomposition, of O Canada and Alouette, Gentille Alouette and the Mendelssohn Wedding March. [My] piece does illustrate the performance nature of the instrument, because all kinds of things happen to each of these pieces as they appear in the composition, but each one was played through and recorded in a single take. All of the changes that are occurring were set up beforehand and then happen during the performance using the pedals and the keyboard. The instrument had a good deal of potential, could even perhaps have been used to make some nice music! [Laughter] I should add that Trudeau’s comment, “Fuddle duddle” at the end, doesn’t belong to this speech. It belongs to another famously reported instance when Trudeau denied saying what he said and when he was asked what he said then, he said: “Oh, fuddle duddle.” I don’t know if any of you remember that, but that was on the news.

I had, I think it was an actor who happened to be working in the electronic music studio, imitate Trudeau’s voice to do that. Just a brief passage, I thought it worked quite well.

As I told you, Dayrand decided that they would undertake the manufacture of this instrument. It was sort of agreed between Dayrand and Le Caine that if this instrument turned out the way that they had expected that they would be interested in manufacturing it. Now, I don’t know at what point they decided not to manufacture this instrument; I think they felt it was too extensive and too complex. It had a lot of pieces but they were repetitive pieces so it might not have been so expensive to manufacture. This was of course back in the days before there were many large-scale integrated circuits or that sort of thing, so a lot of parts were needed. In any event, they decided that they would manufacture a commercial version of Le Caine’s Electronic Sackbut, which had been around since the 1940s. They did in fact get to the stage of producing a manufacturer’s prototype, but at that point, I don’t know if the company folded or if they lost interest. Maybe Gayle knows what happened…

[Gayle Young] It was a combination of delays and figuring out how to build it. As you mentioned, it didn’t use a lot of pre-existing components and then the other synthesizer manufacturers were starting to gain ascendancy in the market; prices starting to go down and I think that was the crucial decision-making factor.

[PP] An interesting thing around this time is that Le Caine retired in ’74, which is just a few years after he had completed the Polyphonic Synthesizer. It could be that the failure of the Sackbut manufacturing project contributed to his decision to retire early. He was 60 at the time.

[GY] Yes, that’s right, exactly 60. He wanted to develop towards research in psychoacoustics. He was working with a young musician named John Chong, who, incidentally, was also a medical student and working for the summer at the National Research Council. [Le Caine] wanted to pass the operation on to John Chong and was preparing a transition. He talked to his superiors about it and they said: “Um, no, sorry. When you retire, the project is over.” He resigned immediately upon hearing that news.

[PP] It’s interesting that you mention, Gayle, that he was interested in going in another direction, because I had speculated that he had stopped interest in the development of his electronic music instruments because of the advent of digital [technologies]. Pulfer’s lab at the NRC was going on at the same time, he was developing an interactive digital system for music composition and real-time synthesis, and I know Le Caine tried out Pulfer’s system and worked with it a bit.

[GY] Yes, he did his piece called Mobile on that system. It was the first combination digital-analogue instrument, and I think Le Caine was still working at trying to figure out what people needed to work with as artists, and he thought we needed an understanding of sound more than we needed different kinds of controls. That is the reason for his change in direction.

[PP] The other thing of course that happened at this time was that the digital equipment took over completely within the decade, and one of the first commercial synthesizers, which we obtained at McGill, was the New England Digital Synclavier, which was insanely expensive, containing a mini-computer. It was quite elaborate and sound storage was still extremely expensive. That company folded a few years later, too. But by 1983 the YAMAHA DX-7 flooded the world with digital synthesizers.

[GY] It seemed like a long period of time as we were there, but in retrospect, it was less than ten years.

[PP] I wanted to play just one more piece, because Le Caine composed a piece on the Polyphonic Synthesizer and called it Paulution, Charnel No. 5. The charnel of course is a repository for dead bodies, and as far as I know, I’m the only “Paul” involved in this thing. [Laughter] Interestingly, I never found out about the existence of this piece until after Le Caine’s death. [Laughter] Le Caine of course had a penchant for humorous or sarcastic titles in pieces, like the title of this symposium [session], “A Noisome Pestilence,” which is the name of one of his pieces as well. This title though I think is a little bit darker than some of the other, more humorous ones. Well, I’d like you to listen to the work, if you haven’t heard it, and see what kind of a work you think it is.

Maybe because of its title, I’ve always thought of this piece as a dirge, or a lament. It certainly has that kind of a sound, for me. Maybe Gayle knows what the subtitle means. I’ve always thought that perhaps he’s identifying the fifth dead body as being the Polyphonic Synthesizer.

[GY] I’ve found no written commentary whatsoever [about this], but I agree with you.

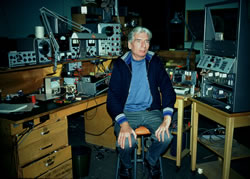

[PP] In a photo taken of Le Caine in his last year at his laboratory (Fig. 5) he looks pensive, at least, perhaps a little sad.

[KA] At the time of the arrival of the Polyphonic Synthesizer at McGill, it was called the “Poly”, and no one realized it was P-O-L-Y, we all thought it was “Paul-E”. [Laughter]

By the way, Hugh Le Caine was this tall [indicates height], six-foot-something, and you can see his hands [in the slide]? His hand was like Rachmaninoff’s hands. You can see the spacing in his hand? That’s the spacing of his mind; everything that went into his head became information for something else to be done. He put things together from all kinds of sources, and he really enjoyed subtle puns as well as the grosser kind as well.

[GY] Thank you very much, Paul. It’s very wonderful to hear your direct experiences of this time period.

[PP] Thank you.

Social top