Talismania (Fetishizing the Fetish)

My latest project examines the vinyl record album as a fetish object. The record LP is transformed into a “meta-fetished object” through the alteration of its original recorded content that is placed onto itself, thus converting the fetishized object from a once mass-produced consumer product into a one of one, mono-print, work of art. The process starts through a decontextualization of a pre-recorded vinyl record by manipulating the sounds of each individual track of the record and then cutting into that same record my processed information. In these instances I’m using a 1940s portable Wilcox-Gay record player and cutter. The project consists of adding my processing to the actual pre-recorded disc, groove for groove, forcing a new layer of information to the previously locked data. I will explore the societal ramifications of Talismania — the fetishization of a fetish through the medium of the record album, from the object’s genesis, derived from its own content to the tautology produced by the melding of this information.

My artistic practice uses noise as a social gathering point. In most instances I open a dialogue between noise and participation in its construction. Noise is the basis of my research in the act of creating a social construct, by first redefining it as not what it isn’t but what it can be. This is achieved by an invitation to create cacophony. In my new project, Talismania, I’m combining my experimental music and (visual) art practices in the creation of an object. The relationship between my music explorations and my visual artworks has always existed in a parallel trajectory but this project is the first to combine my electroacoustic turntablism music with my sculpture and installation practice.

The Turntable Triad: Myself, my Cutter and the Middle of the Road

About Mike

My exploration of noise informs both my visual works and my audio composition, and now these modalities are co-joined in expressing my art form. This has not always been the case; formerly the two followed separate paths. I have an established, intimate relationship with vinyl records. For close to thirty years my experience has evolved from working in the record store to twenty-two years of hosting radio programs on community radio, ultimately extending into visual arts and turntablism practices around the creation of experimental music.. Meanwhile, my visual art practice began when I was in my 20s and moved from painting to installations based in noise. Increasingly, my continued interest in sound and my artwork have now dovetailed. Noise is my fetish and my project Talismania is its idol. To better explain Talismania, I will start by providing a context that informs the project vis-à-vis the Triad and how my visual art practice and my turntabling have become intertwined.

I see noise as a tool for co-creation when the spectator is allowed to define noise through their own creation of it, which inevitably leads to an appreciation of noise. As an improviser by nature, my artistic endeavours unsurprisingly allow others to share in the experience and participate in its collective outcome. I believe all forms of improvisation are controlled in some ways by the Other. This is true in my preferred performance arrangement, where the audience is situated at the same physical level as me, thus eliminating the interstice between spectator and performer. This is also my experience communicating as part of an ensemble during the act of performance either in front of an audience or just jamming. And this extends to my visual artworks, which invites the spectator to participate, allowing for a co-authorship of the experience.

My turntabling practice doesn’t demand clean or pristine vinyl records to be used. I use a Califone 1425 monaural record player, lo-fi, that I have customized through the addition of a second Califone tone arm and a series of contact microphones placed in the body and on the motor of the player (Fig. 1). I have stripped the amplification system from the player and run each tone arm and microphone individually through a Mackie DFX 12 mixer and then process the derived noises into one of two processors (or into both simultaneously), a Kaoss Pad 2 and a Kaoss Pad 3 (Fig. 2). I refer to my turntable setup as my toolbox. I use the mixer’s ability to feed sounds to the two processors, as well as to themselves, allowing signals to be fed into each other and creating unpredictable noise through feedback loops. Sounds are produced through records on the platter as well as via a series of contact microphones placed within the record player itself. The contact microphones invite sounds to be found through the record player’s own operation, such as the hum of motors, and by transforming the body of the machine into a sound-generating platform. The microphones allow for scraping, tapping and the placing of objects to reverberate on the body of the record player. The player itself can be used to generate sounds by the motor and the sounds made by just turning it on to be sampled, to be processed, or both.

Past installation and sculpture works have included both record players and records that were either custom-made, or found and then disguised. Itch (2002) invites participants to improvise in a conducted ensemble of four, eight or twelve members / participants, and to become turntablists. Twelve self-contained institutional record players 1[1. The Califone 1400 series, which includes its own built-in amplifier and speaker system.] are placed on plinths, each having four playback speeds: 16, 33, 45, 78 rpm and a free speed, “0”, where the turntable can be spun freely. Each of the record players includes a record album with its label and its information concealed by a coloured vinyl sticker that is red, yellow, blue or green. The conducting that directs the improvisation is controlled by a computer program that randomly selects colours — red, yellow, blue and green. The colours are generated individually or as groups including all four colours or a blank screen, representing silence, and are projected onto a wall in front of the players or displayed on a monitor (Fig. 5). The camouflaged label veils the content of the contained information, thus dissolving one of the principle tenets of DJing, knowledge of the data found on the record. The labels are also the signifiers used in the conducting, in a sense controlling play within the installation: when a participant’s record label colour is displayed, they are invited to play.

Participants are encouraged to experiment with sound generation from the record and its player in any way they can come up with. This can and does include speed changes and scratching (in both a DJ sense and/or actually dragging the needle across the grooves of the record). The “0” speed bestows upon the participant an ability to manoeuvre the record and/or platter backward and forward or to spin the record in those directions at extremely fast or slow speeds. The use of conducting is not alien to the notion of improvisation and in the case of Itch, conducting is the invitation, lending permission to enter the improvisation that runs concurrently to the open hours of the gallery space.

My sculpture Footlights invites participants to play the record on the player, which becomes the soundtrack to a video of a dancer performing. For Footlights, I produced a custom record, which consists of pre-determined audience sounds: I invited a number of participants to cough and clear their throats for my recording. I edited the sounds together and proceeded to transcribe the information from my computer to my 1940s Wilcox-Gay Record Cutter at 33 rpm. Footlights is constructed out of a self-contained record player. The player has been customized with a hardwood floor surrounding the platter. The record player has a cover which is opened and contains the speaker for the operation of the record player. The sculpture is displayed with the lid open but not removed. The speaker is removed and placed elsewhere within the player; the area that contained the speaker is filled with a seven-inch LCD screen and surrounded by a red velvet curtain that, along with the hardwood floor, reflects the image of a theatre.

When the spectator picks up the tone arm of the record player and places it on the record, the video screen is activated, allowing the dancer to move to the information embedded in the record. A convincing illusion is established, one of the dancer improvising to the audience noises. When the record is finished playing, the record player turns off, as does the screen with the dancer. Footlights is analogous to John Cage’s 4'33", where the audience’s sounds are the pivotal experience.

The Record Cutter

The record cutter I own is a 1941 Wilcox-Gay Recordette 3 (Fig. 4). This record cutter is a portable unit that includes a radio, a microphone and mono RCA plug-in phono jack and sold for $39.98 new. Mine has been customized replacing the microphone with an amplifier that now allows my computer to communicate with the cutter through what was once the phono in jack. The machine itself was one of the first products that would have put copyright issues to the forefront. It allowed the owner to copy songs from the radio, thus bypassing the retailer and label, and creating bootleg recordings of popular songs of the day. (That is another story and another essay.) The record cutter was the first form of permanent data transcription. It was first introduced in radio as a transcription recorder that was used to record performance and commentary to be played back later at 16 rpm on 16-inch wide vinyl plates.

The idea of preserving one’s own sound was not achieved until the invention of the home record recorder / cutter. By now the record player had become ubiquitous in households. The cutter was introduced in the 1930s and was found in homes and in record booths. In my own experience I first learned of the record recorder in a 1961 Flintstones episode, “The Girls Night Out,” in which Fred and Barney decide to treat their wives to a night out at an amusement park. Fred cuts a song at a recording booth as a souvenir but misplaces the record that is later discovered by a group of teens that pass it along to a deejay. Fred is suddenly transformed into unwitting rock star “Hi-Fye”. The record cutter phenomenon was short-lived as magnetic tape took over the market. This is similar to the record and CD relationship. The record cutter and its remnants have now become fetishized.

I purchased my record cutter through eBay and have used it rarely. I have a quantity of blank vinyl records from a handful of manufacturers of the day. In most instances the blank vinyl records had mould or other surface defects, though I don’t find myself curtailed by such things, it does have an effect on the recordings, which at best, are quite low fidelity. In one of my experiments with the record cutter, I decided to record over an already encrypted vinyl record. I started to produce sounds through my toolbox, then cut them on to the pre-pressed record and, to my surprise, the sounds interpolated. The two layers played together. This to me was a phenomenal find. The concept of recontextualising source material is the key objective of both my visual art and musical practices. I set this information aside to let it shape itself into a future reality.

Middle of the Road

While record browsing at the local thrift store, now the main outlet for my record purchasing I found the shelf populated with middle of the road (M‑O‑R) or easy listening records. As a young adult I worked in retail record stores and the stores classified these records as adult contemporary, a scary thought that when I became an “adult” is this the music I was destined to listen to?

The notion of middle of the road or M‑O‑R, places the music somewhere between pop and classical. M‑O‑R is a radio format that used soft, unadventurous music that doesn’t challenge the listener. The music is formulaic; typically pop standards, movie soundtracks and pseudo ethnic songs. They have been converted into an easy listening format involving large orchestras, typically with vibrant string sections and smooth, harmonic choir or ensemble-styled vocals, with featureless arrangements. This styling converts the original song into a euphonious experience for the listener. The stars of the music were bandleaders or arrangers such as James Last, Montovani, Peter Nero, Ray Coniff and Tommy Garrett.

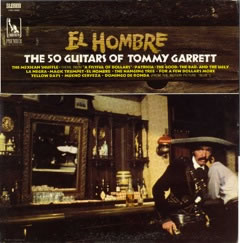

Though a random visit to the local Goodwill thrift shop’s record section lead to the inspiration for the Talismania project. The 50 Guitars of Tommy Garrett’s El Hombre (1968) caught my attention for its use of an ersatz or exotic Mexican musical referencing. Tommy “Snuff” Garrett was an A&R director for Liberty Records and was renowned for giving Phil Spector his first job through Liberty Records. He went on to produce under the name of 50 Guitars of Tommy Garrett, “one of the least adventurous and most easy-listening guitar groups” (The Space Age Pop Music Page).

I grew up listening to easy-listening music in my parent’s home. My mother still speaks of meeting James Last. The music was heard though my parent’s favourite radio station in Toronto. Easy-listening music was on the radio from the time my sisters and I woke up until we went to bed. My parents felt that they were trendy in the 60s when this music was still reaching its peak. In The Acid Archives, Stefan Kery writes: “The older generations’ recreational pursuits like Exotica music and tiki bars were the very definition of square for the burgeoning hippie movement” (Kery 2010, 368). This was the soundtrack to their lives and, by default, mine. I still believe that M‑O‑R music was designed as much to sell as to soothe. It was ubiquitous, heard in malls, offices and elevators — the Muzak of the time. A Los Angeles Times reporter sums up M‑O‑R and its relationship to Muzak in an article from 1974:

A popular tune is selected — say the theme from “The Godfather” — rewritten to Muzak’s specifications, finding the middle of the middle of the road to easy listening by taking out the highs and lows or anything that might catch people’s attention, and recorded in studios in Los Angeles, New York and Germany. The bland, middle of the road (M‑O‑R) music, which is jazzy but not jazz, and which tamely rocks but is not rock, is somewhere to the right of Andy Williams — the king of M‑O‑R. (Murphy 1974)

I found this to be typical of the records I heard in the background of my childhood. The large quantity of product to be resourced through the thrift store bins provides ample raw material for the creation of new works. Re-purposing M‑O‑R recordings transubstantiates a dismissed musical form into a fetishized audio evolution.

Fetishization of the Fetish

Talismania exemplifies the vinyl record as a tool in a means to an end. The triad described above forges a pathway to the completion of this super-fetishization.

It is easy to recognize the fetishism of the record. The music industry’s introduction of the Compact Disc created a mass exodus of the vinyl medium, thus creating the disavowal necessary to produce the fetish object. The record fetishist understands the record’s constraints compared to the ease in sourcing music via the CD or virtually as the MP3, but nevertheless chooses to listen to music on the vinyl medium. Records began to fill landfills and thrift shops as the population disposed of their vinyl collections, fulfilling the music industry’s new business strategy. The shift of medium also affected the electronics manufacturers, causing them to abandon the turntable and replace it with the Compact Disc player.

The sexual connotation of the fetish object proposed by Freud is downplayed by Anne McClintock in Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Context, clarifying the general misunderstanding that is associated with the word and its consistent misrepresentation.

Far from being merely phallic substitutes, fetishes can be seen as the displacement onto an object (or person) of contradictions that the individual cannot resolve at a personal level. These contradictions may originate as social contradictions but are lived with profound intensity in the imagination and the flesh. The fetish thus stands at the crossroad of psychoanalysis and social history, inhabiting the threshold of both personal and historical memory. The fetish marks a crisis in social meaning as the embodiment of an impossible irresolution. The contradiction is displaced onto and embodied in the fetish object, which is thus destined to recur with compulsive repetition. Hence the apparent power of the fetish to enchant the fetishist. By displacing power onto the fetish, then manipulating the fetish, the individual gains symbolic control over what might otherwise be terrifying ambiguities. For this reason, the fetish can be called an impassioned object (McClintock 1995, 184).

The vinyl record was becoming transformed into Marx’s definition of the fetish as “the religion of sensuous desire,” (in Pietz 1991, 136). The notion of the fetish as described by Laura Mulvey in her book, Fetishism and Curiosity, can be seen from two perspectives: one is the Freudian view and the second is Marx’s:

It is in and around the difficulty of establishing the exchange value of actual objects produced under capitalism that commodity fetish flourishes, while the Freudian fetish, on the other hand, flourishes as phantasmatic inscription. It ascribes excessive value to objects considered to be valueless by the social consensus. (Mulvey 1996, 2)

Both aspects are relevant in the redefined significance of the vinyl record.

This duality of the fetishism related to the record is the key to my turntablism practice. The record becomes fetishized through its recontextualized use as tool rather than its passive intent or collectability. The DJ industry, and more specifically hip hop, reinvented the use of the vinyl record. This revitalization of the record brought forth a change in the commodity value of the now supposedly obsolete object. Hip hop surgically disseminated the record for its data through the use of its beats and breaks rather than the music it contained as a whole. In a sense, using only portions of the record as a foundation for the creation of a new song. An experimental turntablist sees the record in a similar fashion, but from my perspective the record plays a different role. Instead of extracting known sounds from a specific point on the record, the recording in its entirety can be randomly sampled. The dissecting of the record for its content is relayed to the listener through the use of electroacoustic means, revamping its original content into process noises that are then rebuilt into a new context, thus escaping the original meaning by the use of external devices in my toolbox.

My work is based on the concept that the record contains information that I can use to generate the base sounds for me to process, but familiarity with the recording is not necessary. I may not know a specific record’s content but I intimately understand the musical genres used to classify recordings, having worked in record stores in my youth and as a librarian in a community radio station. This usage contrasts to hip hop turntable practices (or DJ practices that now have replace the record with the MP3) that require a more intimate familiarity of the specific data contained in a particular recording.

I see the vinyl record as an object towards a means to an end by disguising its data through the means of electronic costuming. My approach differs from turntablist Christian Marclay, who uses the record’s original content to be the fodder of his toolbox. He builds compositions through the use of the actual record’s information with distortions through turntable speed and movement, taking snippets of the sounds and playing them outside of the intended context. In Record Without a Cover (1985), Marclay built a symphonic wall of a record’s unwanted noises through the use of ticks, pops and surface flaws, taking the listener into a new world of sonic intervention. 2[2. See “Christian Marclay — Record Without a Cover (abridged)” for a short version (9:38) of the work with textovers of basic explanatory text on YouTube, uploaded by user “superAJ71” on 20 July 2010.] The recording was actually sold without a cover so that noises and “defects” caused by the gradual wear on the disc would also become integrated into the listening experience.

My process is more aligned with the methods used by players such as Martin Tétreault, Eric M, or Otomo Yosihide, just to name a few. However, similar to Marclay, I use the extraneous sounds of the record itself, such as the ticks and pops of the flawed disc of the intro and outro grooves used to allow the movement of the record needle through the record’s own data. Unlike DJ culture artists or the collector, who require pristine qualities on the disc itself, I search for the flaws and also create them by preparing the records. The preparations of the vinyl take many forms: scratching the records; playing them using unconventional means or using various speeds at which the record was not intended to be listened to; reorganizing the content of the original self by relaying the record’s information through two tone arms; bowing the records with a violin bow; sanding the surface to help disguise the data and add textures not intended in the original recording. This relates to Cage’s prepared piano as well as an improviser’s ability to find an instrument’s flaws thus accentuating them as the primary focus of their playing.

Talismania takes the notion of the fetishized record to a new and highly complex level. The idea of the record cutter rewriting the previously locked information by adding a second layer is a fundamentally new concept. My project transforms the mass-produced commodity into a unique object, or what could be referred to as a Private Press (in record collecting terminology) release or object. 3[3. Private Press is a term used to describe small vinyl record press runs (between one and one hundred) by independent bands in the 1960s, 70s and 80s, usually related to the psychedelic genre of music.] By this I am re-fetishizing the original object.

What I have created is a Duchampian experience of the record album by changing its context without affecting its outward appearance. Mulvey believes Duchamp’s actions to be a fetishization of the everyday item: “The artist chose the objects and, by putting them on show, placed them in limbo in which their use value disappeared and a new æsthetic value was asserted” (Mulvey 1996, 164). She continues her notions of the Duchampian object: “In its mythic apotheosis this tradition merged the creation of the art object with creation itself…” (Ibid., 165). The Duchampian model combined with John Cage’s notion of chance helps to describe my approach to Talismania through my toolbox and turntabling experience.

I use improvisation to create the imposed new layer of data to the record I’m cutting into. The ingrained data of the original song on the disc is played into my toolbox while I simultaneously process the audio material through sampling and various electronic distortions — pitch shifting, grain fluctuations, etc. — of the original material, re-evaluating its content to reinvent the composition. I record this newly invented structure live into Cubase, where I instigate only minimal post-production alterations through gain control, minor editing and tone variations. I try to keep the newly recorded information as true to its improvised performance as possible.

This creation is a fetishized realization of the original data of the found record. At times, when not satisfied with my recording, I will attempt to create a new composition to be layered: having been given clues as to the original content of the record being used, I try to erase these clues from my consciousness. In an artistic sense, I try to forgo my knowledge of the indigenous data found on the source, by moving to other tracks in need of processing and then returning to the ones that require my attention again to achieve this. Hopefully shifting the data into the back of mind and leaving the forefront clear to become, in Deleuzian terms, the body without organs.

Conclusion

The notion of fetishizing the fetish is the basis of my experimental turntabling practices. The transformational process achieved through recontextualising pre-recorded data from the vinyl record transubstantiates the original object. As Marx stated, “the transubstantiation, the fetishism, is complete” (Pietz 1991, 149). So, if transubstantiation completes the fetishism, turntablism accentuates this principle and Talismania takes fetishization further. The layering of these sounds give rise to the source material retaining as prominent a voice as the processed voice. The marrying of these elements birth the meta-formation, a new object, that is housed within the body of the original production, creating this super-fetished object.

Talismania combines a duo of fetish objects — the record cutter, a rare but unaccomplished recording device that was replaced with more conventional and efficient forms of audio capture 4[4. The record cutter as mentioned in the beginning of the essay allowed only for a direct-to-disc recording format, demanding perfect performance, as it refused to allow room for mistakes or accidents. This was replaced by the reel-to-reel tape recorder, which invites multi-track recording and editing and allows for correction of mistakes, sound manipulations such as volume correction, equalization and the introduction of various effects such as reverb, echo and layering of multiple sounds after the recording process has occurred, through post production techniques. The reel-to-reel has now been replaced by the computer, whose virtual storage abilities allow for infinite post-production techniques to exist, depending on hard drive space, computer memory and the post-production skills of technicians.], and the record, that was displaced by the CD — which is then fetishized by the creator (musician / artist / improviser) through the act of experimental turntablism, culminating in the work-of-art-as-fetish (Bourdieu 1996, 203). This meta-fetishized object becomes the one-off vinyl record, a rarity in the field. The series will continue as I explore other M-O-R recordings and manipulate the data to formulate the subsequent works in this on-going exploration of meta-fetishized turntablism. Utilizing this form of production invokes the Duchampian mode of recontextualization. In a world that is becoming more and more virtualized, Talismania reverts to what can only be described as fetishistic means of production to create a totem in the form of objets d’art.

Bibliography

Bourdieu, Pierre. The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field. Trans. Susan Emanuel. Palo Alto CA: Stanford University Press, 1996.

Kery, Stefan. “Seeking the Lost Idols of Exotica (A Tiki Bat Trialogue with Stefan Kery and Will Louviere).” The Acid Archives, Acid Archives Special Feature. Stockholm, Lhasa, Mojave: Lysergia, 2010. Second printing.

Lundborg, Patrick. The Acid Archives, A Guide to Underground Sounds 1965–1982. Second Edition. Stockholm: Lysergia, 2010.

McClintock, Anne. Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Context. New York and London: Routledge, 1995.

Mulvey, Laura, Fetishism and Curiosity. Bloomington and Indianapolis IN: Indiana University Press, 1996.

Murphy, Mary. “Muzak makers hope you don’t hear the manipulating.” Los Angeles Times Services, published in The Milwaukee Journal. 12 March 1974. Available online via the Los Angeles Times Service [last accessed 31 August 2012]

Pietz. William. “Fetishism and Materialism: The Limits of Theory in Marx.” Fetishism as Cultural Discourse. Edited by Emily Apter and William Pietz. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1991.

“Tommy Garrett.” The Space Age Pop Music Page. http://www.spaceagepop.com/garrett.htm [Last update 2008]

Žižek, Slavoj. For They Know Not What They Do: Enjoyment as a political factor. Second Edition. London and New York: Verso, 2008.

Social top