A Phenomenological Time-Based Approach to Videomusic Composition

Return to previous section (Chapter 2: Movement and Gesture in Videomusic)

Chapter 3: Analysis of the hands of the dancer

3.1 the hands of the dancer

The hands of the dancer is a 21-minute HD videomusic piece that focuses on imagery related to the mythology of temple dancers and to dreaming. A man sleeps and dreams of a dancing girl who multiplies and shimmers like the desert. Her image is continuously mutating and becomes the landscape of his dream. She looks into a mirror and appears next counting peacock feathers while a priestess takes her place as the dancer, making contact with the dreamer.

This video explores the multiple ways that movement and form can be abstracted through surface and temporal manipulation. The narrative evokes a dreamscape in which characters exchange identity and develop through physical transformation. The sounds and images depicted are inspired by traditional Baladi form and are meant to evoke a state in which these bodily gestures convey secret meanings that need not resort to spoken language.

In the hands of the dancer, the method by which both the characters and their surroundings change and replace themselves is inspired by the memories I have of my dreams. In these dreams, characters and places are not fixed, but instead evolve continuously while maintaining their identities until a significant change of context has occurred. Time is not linear in my dreaming experience; instead it reshapes itself around specific events with variable rate. Connections between disparate elements and experiences are formed based on superficial similarities. These connections are strong enough to join the moments that inspire them in some inexplicable way, so that they can no longer be differentiated in my memories afterward.

Many narrative developments in the hands of the dancer are taken from fragments of my dream recollections. I did this to enhance the sense of dream-state I wanted to create for the viewer, rather than to construct a specific storyline. When the dancer who is predominant in the first half of the piece stares inside a mirror (Fig. 1), her reflection has been replaced with that of someone else. In the next movement of the piece, only this new girl performs. The first dancer is cast into a new role where she is represented in a different colour palette, counting peacock feathers and kneeling. In my description of the piece I refer to this new dancer as a priestess because of her magical, transformative role in the narrative.

I drew upon two separate dream experiences in the creation of this image. In the first, I stared into a large mirror. After a moment, my reflected double detached itself from its role, to lean towards me and advise me with secret teachings I could not have attained any other way. The second experience that inspired this image is a seemingly common dream device whereby one character is replaced with another in the narrative suddenly and unquestioningly. In my dreams, when this occurs, it is as if different actors are portraying the characters. The role has not changed and it is only in retrospect that I notice the transference of identity.

Figure 1. A still from the hands of the dancer. The dancer stares inside the mirror and finds her reflection has been replaced with that of someone else. [Throughout this article, click on any image for more detailed study.]

Figure 2. A still from the hands of the dancer. The new dancer is performing and two arms are seen to reach forwards from the sides of the screen. These arms belong to the character from whose gaze the scene is depicted.

Another example of an event in the hands of the dancer that was inspired from one of my own dreams happens when the new dancer is performing and two arms are seen to reach forwards from the sides of the screen (Fig. 2). When dreaming, my awareness is not always centred in the first person. In fact, in the same dream narrative I might experience events sometimes as if I were present in the scenario and other as if I were viewing them from a passive third person perspective akin to a cinematic experience. When my dreams unfold from a first person perspective, my own body is often mostly unnoticed by me. The only exception are my hands and arms, which, when I raise them, appear almost as disembodied limbs extending from the periphery of my vision. The introduction of such arms in the hands of the dancer hint at a presence who exists within the narrative of the piece but is hidden behind the gaze from which the narrative is staged.

Aesthetically, the hands of the dancer initiates a three-part dialog between concrete image, abstraction, and surface manipulation. With the very few exceptions of some occasional props such as peacock feathers, flower petals, and a mirror, all the imagery created for the piece stems from transformed material of the same three different models. Much of this material has been abstracted into landscape and architectural elements (Fig. 3) but can still be related to their origin either through colour and textural properties, or through details left from the original image that are still discernible after transformation. Because many of these transformations happen within the piece itself, memory adds to the identity of these fragments, associating them with their previous incarnations. In this way, abstracted visual elements can refer to each other, as well as to the material from which they were derived, even after significant processing.

The same small bank of material is used extensively throughout the piece under different transformations. In this way these images become recognizable and easier to extract from their context even when altered. The gestures and movements of the people depicted within begin to carry a thematic meaning as they are echoed and referenced by other related material. In figure 4, two moments when a dancer passes her hand over her face are contrasted. In both of them, the physical gesture is recognizably the same (as is the dancer), however, the footage has been given a separate identity by both its context and its processing. The repeated physical gesture allows a relationship to form between these two separate moments in the piece. This is not a relationship of strict repetition as the other elements in the image are not the same and the image is developed somewhat differently in relation to them. Were the footage used with different beginning and end points, or were it used at a different speed, this would also help differentiate its identity. A similar technique is used in the audio component of the piece when sounds are repeated outside of their original context. The connection between the separate moments in which that sound is heard exists as a function of how much its identity has changed, either through its processing, editing, temporal manipulation, or context.

Few cuts are used in the piece. Instead, a sense of continuous transformation is maintained, with occasional pauses used in order to shape the compositional flow and emphasize particular imagery. Because related or even identical footage is used throughout this process, the successive transformations cause a narrative to emerge through which the different models (now identified through the narrative as characters) are able to maintain some kind of consistent identity based on their recognizability (Fig. 5). This narrative is not set in the real world. The narrative is both self-referential and interconnected, through the recognizably transformed footage used in its construction. It is not linear, similarly processed material occurs disparately throughout the piece, and some successively manipulated material is used in reverse to give the impression of its own undoing. The characters themselves appear alongside their own multiples or interact with abstract elements created from previous versions of themselves. Events are not presented as discrete, under which guise they could appear as extracted moments from a more realistic temporal scale. Instead, they bleed into each other and merge together, fading in and out of existence. Each character’s identity is preserved throughout these transformations and new beginnings by their continual re-emergence. The strict use of a shared colour palette contributes towards each character’s recognizability while undergoing such visual regeneration.

The dialog that is initiated between concrete image, abstraction, and surface manipulation throughout in the hands of the dancer relies on the discernible identities of the separate characters. These identities help to classify visual material towards a concrete referent, expanding the partial state between abstract and concrete form so that visual material can exist indeterminately between them. Surface manipulation acts as a separate dimension of perceptual grouping on visual imagery, as it functions at least partially independently from the abstract-concrete continuum. Applying surface manipulation to an image does not necessarily destroy its recognizability; instead it changes its visual context. Distinct visual elements can be unified through shared surface manipulation into a common visual plane. The top right image of Figure 5 illustrates this fact. Inside the image, several versions of the same dancer are depicted on a common plane that has been separated into three overlapping parts through surface manipulation.

A similar æsthetic dialog to the visual one occurring within the hands of the dancer can be constructed through sound. Sound too can be abstract or can reference concrete reality. The surface manipulation of an image finds its aural counterpart in the collection of temporal and spectral sound manipulation tools commonly available inside sound processing software. I have made no effort, however, to structure this dialog in tandem across the aural and visual components of this piece though it can be found in both.

The dialog between abstraction, concrete form, and transformation accomplished through sound processing, is a popular one in electroacoustic music and is almost impossible to escape when recording technologies and sound manipulation are the primary tools of a composition. The similarity in the visual and aural æsthetic language of the hands of the dancer arose from my desire to portray dream-like imagery and my perception of electroacoustic composition in terms of its temporal malleability. I desired to impart this malleable attribute to my visual work, and so I set out to engage with it in a similar fashion to the way I would engage with my materials when composing an electroacoustic piece. I did not reflect any purposeful, structural, discourse between concrete elements in my aural and visual media because I did not want to emphasize the concrete reality from which my sound materials stem. The only subject matter of my piece is the characters and the ways in which they are transformed and interact with these transformations.

Aural thematic content in the hands of the dancer is used in the same way as my continuous colour palette, to help categorize visual material towards an identifiable source. To use identifiable aural content in a more structured mapping with the visual material would allow the soundtrack to enter too fully into the realm of the diegetic, where sounds belong to objects for the extent of their existence rather than as a temporary artifact of movement. Such a mapping would make the soundtrack the sound of the dream depicted rather than a poetic accompaniment to what is essentially an ethereal world. The synchretic relationship between sound and image, in its discontinuity, already straddles these two territories. Instead, I chose to use the soundtrack to help extend the perceptual qualities I wanted to express with my dream imagery, by using shared movement and gesture in sound and image to different temporal affect.

3.2 Analysis of the hands of the dancer with Regard to Movement and Temporal Affect

The composition of the hands of the dancer is distributed throughout visual and aural gestures as well as through gestures that unify both media. The tension that contrasts shared and separate movement in the visual and aural domains defines the experience of the piece. Sounds and images are paired through the simple mechanism of being placed together temporally in a synchretic relationship so that they are felt to belong. As a result, they appear to share their movement and inform each other perceptually through trans-sensorial communication. In these instances, both the spatial and temporal movement exhibited by the combined gesture is enhanced perceptually, and the relative factors that define the movement compared to its context exert a perceptual influence over the viewer’s engagement with time. The main factors that shape this influence are rate of change, duration, speed, and continuity.

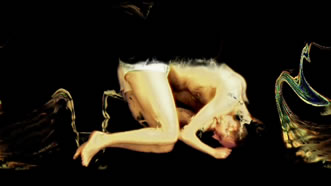

Several examples can be found in the hands of the dancer where aural and visual movements combine to make a single gesture. These gestures integrate the visual and aural components of the piece into a meaningful relationship defined by their shared movement. One example of such a gesture, repeated with a variation, occurs early on in the piece when the dreamer is curled up in between the foetal position and one suggesting sleep (Fig. 6). The visual abstract elements in the image rise upwards through a combination of movement and surface manipulation, while at the same time a long sound of ascending pitch, ending in high and shimmering frequencies is played (Video 1). The movement, reflected in both the sound and image, unite in this gesture, to create a sense of motion that is deeply emphasized over its surrounding context. The visual gesture is a slow one and the addition of sound steadies the movement, making it appear even slower.

Figure 6. The visual abstract elements in the image rise upwards through a combination of movement and surface manipulation.

Figure 7. The visual abstract elements of the piece pulse amorphously while the sound of breath is heard.

In the same section of the piece, not long after the rising gestures recently described, another interesting temporal phenomenon occurs that can be attributed to the relationship between the sound and image. For approximately ten seconds, the visual abstract elements of the piece pulse amorphously while the sound of breath is heard (Fig. 7). If this material is watched without sound, the movement is perceived as continuous, with slight fluctuations defining a pulse. When the sound of breath is played over this material, the amorphous visual movement seems to gather around the temporal structure of the sound. The dynamic contour of the sound helps define the amorphous visual movement into a shared gesture (Video 2), one that shares a beginning and end.

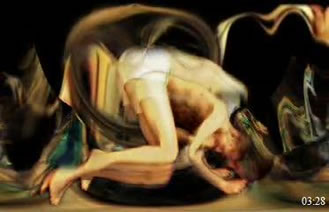

Not only can the relationship between sound and image define and strengthen a gesture through temporal emphasis, it can also define which parts of a movement appear relevant. In the second half of the hands of the dancer, the character I have referred to as the priestess appears in multiple concurrent incarnations, each under various levels of abstraction. These incarnations each contain many threads of movement at the same time (Fig. 8). This movement is not reflected in the soundtrack. Instead, the soundtrack for this section consists of a repeated motif of ascending and descending short notes, sweeping resonant frequencies, and a rhythmic pattern with some variation introduced from its processing. Of all of these sounds, only a fraction occurs with motion of a similar speed to that depicted in the image. The visual movements that synchronize with this fraction are emphasized, and dominate the visual conglomerate of motion. The result of this imbalance is a small amount of temporal distortion, whereby the moments when sound and image unify through similar motion appear longer (Video 3).

Figure 8. Each incarnation contains many threads of movement at the same time.

Figure 9. The image contains only arrested movement.

Movement can also emphasize the duration of a partially synchronized gesture, by continuing past or stopping before its end. In a repeating gesture that takes place near the end of the hands of the dancer, the second dancer’s image is arrested mid motion (Fig. 9) and then slowly fades away while the sound that has been accompanying its movement continues. The slow visual fade to black is perceptually shortened relative to the continuing sound (Video 4). This effect results both from the break in continuity between the aural and visual motion and from the contrasting speed of the movement that is present afterwards.

Repetition is a device that is commonly used to help structure melody. During the section of the hands of the dancer before the dreamer is re-introduced, the priestess figure is shown with residues of her movements trailing behind her like the feathers of a peacock. She is replaced with a more fluid visual interpretation of the same footage and is placed beside herself three times (Fig. 10). The soundtrack during this section is filled with a repeating vocal fragment that orders the visual repetition into a sense of metric structure that does not exist without the sound present (Video 5).

Temporal distortion is caused as a result of synchresis and the perception of relative motion. As previously mentioned, relative motion relies on rate of change, duration, speed, and continuity. The next three examples from the hands of the dancer demonstrate the manipulation of relative motion through its contributing factors. In the first example, the frame begins to fill itself with stills extracted from a sequence in which the motion of the priestess figure has been visually emphasized. These stills appear quickly and then fade to black after a few seconds, however, in the interim, the frame fills with many such stills at once (Fig. 11). After a significant mass of these still images has been accumulated, they all disappear at the same time, to be replaced by an image of the dreamer, similarly processed, sitting up and then lying down. The sound that accompanies the separate still images of arrested movement as they fill up the frame has both synchronized and unsynchronized elements. Over the course of this sequence, the visual and aural events become less and less synchronized, until they are all dissolved and replaced by the dreamer. The aural gesture that accompanies the dreamer shares his motion. This onslaught of chaos replaced with order, gives the sensation of time accelerating towards a fixed point of apparent stable motion (Video 6). This effect is achieved essentially through varying the location of sound and image events so that tension created through their mismatching is heightened and then resolved.

Figure 10. The same footage depicting the priestess figure is placed beside herself three times.

Figure 11. The frame fills with stills, depicting arrested movement.

Figure 12. The priestess figure in a heightened state of surface manipulation which multiples the motion about her figure.

Figure 13. The dreamer is seen moving while a mass of colour dissolves and ripples around him.

A sense of continuous relative motion can be created through the contrast of several independent elements moving discretely. When the priestess figure first begins to dance, she is depicted alone in a heightened state of surface manipulation which multiples the motion about her figure (Fig. 12). The abstract material that surrounds her also moves in with a similar pulse. The soundtrack that accompanies her, however, contains a rhythmic element whose tempo is not reflected in the frame’s visual momentum. The net effect of this tension is a negative relative motion that slows the visual movement down when it is experienced with the soundtrack (Video 7). The same visual material alone is experienced differently.

A final example from the hands of the dancer depicting temporal affect, achieved through the tools of relative motion and synchresis, occurs when the sound and image being presented together accelerate at different rates. In the last image sequence of the piece, the dreamer is scene moving while a mass of colour, echoing the colours of the priestess figure, dissolves and ripples around him (Fig. 13). The sound in this section is in a slow crescendo that moves with an accelerating arc. The visual movement in the image does not have the same sense of acceleration although it does continue to move with some gestural variation. The slow and steady acceleration of the sound seems to steady the quicker changes in the visual movement. Any visual motion that surpasses the acceleration of the sound becomes emphasized and seems to move more quickly than it does alone. The rest of the movement in the visual field slows down as the aural acceleration surpasses it (Video 8).

Many more examples of relative motion and synchresis can be found in the hands of the dancer. The perceptual consequence of the way these different effects interact, portrays time as something fluid and unstable, and so, adds to the sense of dream imagery and narrative depicted within the piece’s content. The hands of the dancer was not constructed in order to demonstrate the close ties between videomusic composition and perceived movement, rather a dialogue concerning relative motion and synchresis can be constructed to analyze any such work. These effects are present whenever sound and image are combined into a whole, and together they determine how this whole will be perceived.

Conclusion

Videomusic is well situated in the domain of visual music for investigating temporal affect because of the fluidity of its working methodologies and because its discourse focuses on the engagement of gesture as expressed through both sound and image. Compositions that engage with moving sound and image components have the possibility of achieving an experience quite different than either sensory experience could produce alone. By exploiting the perceptual relationships that binds aural and visual material, different small-scale manipulations of temporal perception occur. These manipulations give time a very fluid depiction in such practice. More detailed study of this effect is necessary to see to what extent it can be used in composition, however, the discussion of videomusic in terms of shared gesture and relative movement creates a framework for analysis that considers the experiential quality of videomusic work.

Notes

- Though Schaffer himself encouraged a form of listening called écoute réduite, in which real world sounds are purposefully heard without reference to their physical origins (Landy and Atkinson 2002).

- This psychoacoustic effect among others, has been studied extensively by Albert S. Bregman, who termed the way that sounds are grouped together or separated into distinct acoustic objects or events auditory stream segregation (Bregman 1990).

Glossary

Affect and Effect

Both the terms affect and effect are used in this paper. An affect brings about a change in psychological or cognitive state. It is different than an effect that is the result of a process. The subject matter of this paper is such that many of the effects that I discuss are also affects. To complicate matters, both words can be used as verbs or nouns. I generally use the word effect when I am describing a perceptual result and the word affect when I am describing the way that result is communicated in perception.

Electroacoustic

I have chosen to spell the word electroacoustic without a hyphen. Many spellings of this word are common in the genre. I believe that the main dialog of this medium is not in the way electronic and acoustic material is integrated, rather it is the way they are presented, however, in the French language, the word electro-acoustic specifies a larger technological framework than that concerning composition. In deference to the French electroacoustic tradition I am omitting the hyphen between these words.

Inter-Sensory, Soundtrack, Dreamscape

I have chosen to present other combined concepts as a single, non-hyphenated, object only if their integration denotes a concept larger than their combined scope. I have only observed this convention where a common standard has not been adopted for the spelling of the word.

Videomusic

I have chosen to continue the tradition, already present in the field of electroacoustic composition, of spelling the term videomusic without a space between the words video and music. This spelling emphasizes the close relationship between image and sound that occurs in its practice and distinguishes it as a discipline separate from that of video or sound production.

Visual Music and Videomusic

The term visual music was coined in the context of film to describe non-narrative sound and image compositions that are informed by musical structure. The term videomusic arose in the electroacoustic community to describe composed works for video where the soundtrack and visual component are tightly integrated. Videomusic works draw from the rich traditions of both experimental film and video art while inheriting the compositional vocabulary of electroacoustic music. Videomusic is a sub-genre of visual music explicitly related to electroacoustic music and video.

References and Citations

Apple Inc. “iTunes Overview.” Apple — iPod + iTunes. 1 April 2008. http://www.apple.com/itunes/overview

Aristotle. “De Sensu.” The Works of Aristotle. London, UK: Oxford University Press, (1907), pp. 439b.

Arnheim, Rudolf. “A Review of Proportion.” Module, Proportion, Symmetry, Rhythm. Ed. G. Kepes. New York: George Braziller (1966), pp. 218–230. Quoted in Evans 2004.

Becker, Leon. “Synthetic Sound and Abstract Image.” Hollywood Quarterly 5/1 (1946), pp. 95–96.

Bregman, Albert S. The Perceptual Organization of Sound. Cambridge MA: MIT University Press, 1990.

Chion, Michel. Audio-Vision — Sound on Screen. Ed. and trans. Claudia Gorbman, foreword by Walter Murch. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Collopy, Fred. “Color, Form, and Motion: Dimensions of a Musical Art of Light.” Leonardo 33/5, Eighth New York Digital Salon (2000), pp. 355–360.

Cowles, J.T. “Experimental Study of Pairing Certain Auditory and Visual Stimuli.” Journal of Experimental Psychology 18 (1935), pp. 451–460. Quoted in Peretti.

Cycling 74. “Max/MSP/Jitter Product Overview.” Cycling 74. 1 April 2008. http://www.cycling74.com/products/mmjoverview

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 1: The Movement-Image. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983.

DeWitt, Tom. “Visual Music: Searching for an Aesthetic.” Leonardo 20/2, Special Issue: Visual Art, Sound, Music and Technology (1987), pp. 115–122.

Ekman, Rasmus. Coagula — Industrial Strength Color Note Organ. 7 June 2003. Developer’s website. 1 April 2008. http://hem.passagen.se/rasmuse/Coagula.htm

Evans, Brian. “Establishing a Tonic Space with Digital Color.” Leonardo Supplemental Issue 1: Electronic Art. The MIT Press (1988), pp. 27–30.

Evans, Brian. “Temporal Coherence with Digital Color.” Leonardo Supplemental Issue 3: Digital Image, Digital Cinema: SIGGRAPH “90 Art Show Catalog (1990), pp. 43–49.

Evans, Brian. “Elemental Counterpoint with Digital Imagery.” Leonardo Music Journal 2/1 (1992), pp. 13–18.

Evans, Brian. “Musical Time in Visual Space.” Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference (ICMC) 2004 (Miami, USA, 2004).

Helmoltz, H.L. On the sensations of Tone as a Psychological Basis for the Theory of Music. New York: Dover, 1954. Quoted in DeWitt.

Hevner, Kate. “Experimental Studies of the Element of Expression in Music.” American Journal of Psychology 48 (1936), pp. 246–268. Quoted in Peretti.

Kandinsky, Wassily. Concerning the Spiritual in Art. New York, NY: Dover (1977), p. 25. Quoted in Poast.

Landy, Leigh and Simon Atkinson. “Reduced Listening.” 2002. Ears: ElectroAcoustic Resource Site. Music, Technology and Innovation Research Centre at De Montfort University. 15 July 2008. http://www.ears.dmu.ac.uk/spip.php?rubrique219

Luscher, Max. The Luscher Color Test. Ed. and trans. Ian A. Scott. New York NY: Random House, 1969, p. 12. Quoted in Poast.

Manovich, Lev. The language of new media. Cambridge MA: MIT Press. 2001.

Massumi, Brian. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durhum & London: Duke University Press, 2002.

McWilliams, Donald. Norman McLaren Biography. National Film Board of Canada. 15 March 2008. http://www3.nfb.ca/animation/objanim/en/filmmakers/Norman-McLaren/overview.php

Noë, Alva. Pictures in Mind. Action in Perception. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004.

NullSoft. Winamp Media Player Overview. Winamp Media Player. 1 April 2008. http://www.winamp.com/player/overview

Pedroza, Carlos. Visual Perception. Encyclopedia of Educational Technology. Ed. Bob Hoffman. The SDSU Department of Educational Technology. 2 March 2007. http://coe.sdsu.edu/eet/Articles/visualperc1/start.htm

Peretti, Peter. “A Study of Student Correlations between Music and Six Paintings by Klee.” Journal of Research in Music Education 20/4 (Winter 1972), pp. 501–504.

Poast, Michael. “Color Music: Visual Music Notation for Musical Expression.” Leonardo 33/3 (2000), pp. 215–221.

Pocock-Williams, Lynn. “Toward the Automatic Generation of Visual Music.” Leonardo 25/1 (1992), pp. 29–36.

Popek, B. Classical Guitar Dictionary G. Classical Guitar Sheet Music and Tablature. 2 March 2007. http://www.cgsmusic.net/Classical Guitar Sheet Music Dictionary/Classical Guitar Dictionary G.htm

Russet, Robert. “Animated Sound and Beyond.” American Music 22/1 (Spring 2004), pp. 110–121.

Samual, C. and F. Aprahamien. Conversations with Olivier Messiaen. London, U.K.: Stainer and Bell (1976), p. 17. Quoted in Poast.

Snyder, Robert R. “Video Color Control by Means of an Equal-Tempered Keyboard.” Leonardo 18/2 (1985), pp. 93–95.

Wehner, Walter. L. “The Relation Between Six Paintings by Paul Klee and Selected Music Compositions.” Journal of Research in Music Education 15 (1966), pp. 220–224. Quoted in Peretti.

Whitney, John. “To Paint on Water: The Audiovisual Duet of Complementarity.” Computer Music Journal 18/3 (Autumn 1994), pp. 45–52.

U&I Software Inc. “Metasynth 4.” Product page. 1 April 2008. http://www.metasynth.com

Zmoelnig, Iohannes M. The Pure Data Portal. April 2 2008, Pure Data — PD Community Site. April 15 2008. http://puredata.info

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Jean Piché for showing me what works, Kevin Austin for his guidance and inspiration, and Shane Turner for all the love and support I never thought to ask for. I would also like to thank Jesse Staniforth for making sense of my thoughts when I set out to apply, Judith Cookson for proofreading this paper, and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for funding one year of my study. Really. Thank you.

I am also genuinely grateful towards Olivia Li, Andrea Fryett, and David Drury who all modelled for me without question and who appear in the videomusic work analyzed in this paper. I hope you enjoyed your role in the hands of the dancer. Thank you for dreaming with me.

Social top