[Entrées]

Introductory texts about composers and their works by students and emerging authors

Marcelle Deschênes — Indigo (2000)

Biography and Analysis

Gilles Gobeil, Robert Normandeau, Louis Dufort, and Jorge Sad are only a handful of the students once under the awning of apprenticeship with Marcelle Deschênes. Her knowledge and wisdom in the field of electronic music, namely acousmatics, has earned her numerous awards and global recognition for outstanding achievement in the realm of sonic arts.

Biography

Born in Price, Québec, on the 2nd of March 1939, Deschênes grew up in a strictly French environment. Working with Jean Papineau Couture and Serge Garant at the Université de Montréal, Deschênes earned a Bachelors degree in Music and proceeded to complete what was called a License in Music or LMus (Daunais and Plouffe, 2007). This was a program of two additional years to the BMus designed to allow the student to specialize in a specific topic, whether it is theoretical or historical, and gain a higher education. The program was later renamed to a Masters in Music for simplicity in the North American school system. After completing a number of doctorate level courses, Deschênes obtained a grant from the French government, the Québec government, as well as the Canada Council to continue her education in Paris, France. In 1968 and 1969 Deschênes worked at the Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRM) with, among others, François Bayle and Guy Reibel (Daunais and Plouffe, 2007). Deschênes also spent some time, through the GRM and their workings in publication of musique concrete, at the Office de Radiodiffusion Télévision Française, better known as the ORTF.

In 1971, after being absent for three years, Deschênes returned to Québec to prolong her work in sonic art and acousmatics by taking part in a cooperative work entitled Si… longtemps, which was performed at the Université de Montréal in 1972. She composed, produced, and directed the joint work (Daunais and Plouffe, 2007). In 1972, Deschênes continued to do research at the Université de Laval where she would end up working for the next five years. Her lectures were on topics such as auditory perception, musical pedagogy for children, and multi-art animation techniques. Never ceasing to compose, Deschênes’ electroacoustic art is consistent throughout her life, frequently working on multimedia presentations and installations with other artists. By 1980, at the age of 41, Deschênes began working as a professor at the Université de Montréal (U de M) where she spearheaded the Electroacoustic Composition bachelor’s, master’s, and PhD level programs (Couture, 2006). It is largely due to Deschênes’ input at U de M that the school has developed a certain “sound” or “character” of artistic output. According to Dr. Mark Corwin, full-time professor of electroacoustic studies at Concordia University, U de M’s graduates have a distinct stylistic quality that distinguishes them from most other university programs in this faculty. The heavy focus on texture and specialization in acousmatic content shapes the students in a distinct way. Deschênes’ career at U de M ended in 1997, however she still resides in Montréal and continues to work in composition and creation.

As an end note, Deschênes’ work in the field of sound art in Québec is somewhat masked behind the superstructures of associations and communities throughout the province and nation. Deschênes is “a founding member and director of: ACREQ (Association pour la création et la recherche électroacoustiques du Québec), Action multimédia (with the company Écran Humain), FATNA (Fondation pour l’application des technologies nouvelles aux arts), Nexus (multimedia organization); and a founding member of CEC (Canadian Electroacoustic Community).” (empreintes DIGITALes, 2007). Dr. Rosemary Mountain, an accomplished music theorist and composer, and professor at Concordia University, had very strong words regarding Deschênes’ art work:

Although many electroacoustic works convey the notion of energy to me, few have captured such a range and subtlety of emotion. Her mastery of sound enables her to carve it into evocative shapes, creating an emotional impact that will make all but the most cold-hearted analysts focus on the musical content rather than on the expert technical skills employed. (Mountain 2003, 14)

Marcelle Deschênes — Indigo (2000)

Indigo is found on Deschênes’ latest disc, entitled petits Big Bangs, released in 2006 on the Montréal label empreintes DIGITALes. The album contains six pieces composed from 1985 to 2000: Big Bang II; Indigo; Le bruit des ailes; Lux; Moll, opéra lilliput pour six roches molles; and Big Bang III. The collection was released on DVD-A, and is currently available online. Indigo had its premiere in Montréal at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal on October 31st, 2000 (Couture 2007); Halloween being a fabulous occasion given the sounds and styles within the piece.

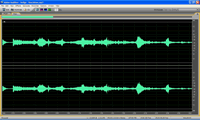

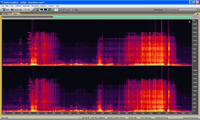

The piece is 10m40s long and was played at the Oscar Peterson Concert Hall on February 9th, 2007 at 17h00 as a part of the ÉuCuE concert series. It was realized in 7.1 surround and Marcelle Deschênes was present at the event. It is a piece designed in two sections with numerous acousmatic samples juxtaposed on relatively recognizable sounds. It contains quotes from other electronic pieces such as L’impatience des limites (1992–93) by Bernard Fort, Derrière la porte la plus éloignée… (1998) by Gilles Gobeil, and Électro-Prana (1998) by Jean-François Laporte, along with some early music samples (Couture, 2007). The two sections are entitled Peur apprivoisée and Trame de tension, each being based on a historical folk tale, Bluebeard by Charles Perrault and Snow-White and Rose-Red by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm respectively.

Part 1: Peur apprivoisée (0:00–2:51)

Prior to the analysis of Part 1, it is important to note that the time markers are being judged by me as a listener, they are not direct program notes from the composer. Also, in order to better explain Indigo, I have chosen to write about the folk tales by which the piece is inspired, the endings of the stories will be spoiled and if it is at all possible I would encourage the reader to read these short stories prior to reading the analysis.

The opening section of the piece is based on a folk tale by author Charles Perrault called Bluebeard. First published in 1698, the tale is of a wealthy man named Bluebeard who is known to be hideously ugly. All of his wives have disappeared in time and no one has any idea where they have gone. Bluebeard seduces a young woman to marry him and when away for a long period of time he leaves her the keys to the estate but forbids her to enter one closet at the end of the hallway. In her tireless curiosity, Bluebeard’s wife eventually opens the closet to find the floor covered in blood and the slain bodies of all of Bluebeard’s former wives hung on the walls. Upon his return, Bluebeard is infuriated by the fact that his wife has disobeyed him and seconds before beheading his wife, he is killed by her brothers.

Upon reading the folk tale and hearing the piece, the sounds and compositional techniques were much more vivid and clear. The samples of doors creaking and the fabulous use of chant and epic background sound is a perfect back plate for the recognizable noises throughout the beginning. The use of rhythm to build stress and anxiety during moments of distinguishable movement and action is brilliant and well calculated. There is an eerie sense that leaves the listener constantly wondering. Short bursts of polyphonic sound collages come into the foreground and provide the listener with something to hold onto before it disappears back into the darkness of sound. At 1:11 the sound of an opening door is introduced and gives the listener the impression that the wife has just entered the forbidden room at the end of the hall. There is a period of about 18 seconds before another forefront sound is introduced. These are perilous moments of anxiousness as the listener waits for a resolution picturing the woman peering around the room in horror. The final peak comes at 2:38 when there is a moment of heightened amplitude until 2:31 when a mechanical noise sets in and the stress begins to relax until the chant is reintroduced at 2:52.

Part 2: Trame de tension (2:51–10:40)

In Part 2, the piece very calmly ascends until around 4:02 when there is a fade in of a camera-like sound and a bunch of rhythmic gallops through the stereo image. Although the feeling of tension is somewhat preserved from the first section, the samples have changed and the sense of openness and the outdoors seems to be more important with wind sounds and droning chants. Part 2 is based on another folk tale, this one by two authors, Jacob Ludwig Grimm and Wilhelm Carl Grimm. The tale is entitled Snow-White and Rose-Red. It is a story of two girls, their mother, a bear and a dwarf. The bear befriends the two girls and their mother throughout the winter and when summer arrives he tells them that he must go and deal with a dwarf who has caused him trouble. During the summer, the two girls encounter a dwarf on four separate occasions, always setting him free from a troublesome situation, twice by cutting his beard free when it becomes knotted in a tree and a fishing pole. On the fourth occasion however, the two girls encounter the dwarf with riches and the bear intrudes and as the dwarf pleads for his life, the bear bats him to the ground and kills him. As a result, the bear sheds his coat and reveals himself as a man cast under the spell of the dwarf who stole his fortune.

There are numerous sounds which are directly related to the narrative within the second section of Indigo. At around 7:38, samples of water begin to enter slightly before a very aggressive slicing noise, which is very evocative of the scissors that the girls use to cut the dwarfs beard free of the fishing pole. As all of these sounds begin to speed up into a larger and more spectrally widened mirage, it climaxes at 9:25 into a very still silence as the bear clobbers the dwarf and growls at 9:42, leaving the listener until the end of the piece. Once again Deschênes has a brilliant use of sounds to build imagery and powerful motives.

Technique

Deschênes has a formidable ability to use gesture to capture the listener. Indigo is inspired by actual narratives and its sound sources are distinctly recognizable, allowing the listener to embark on a voyage where he or she can objectively imagine a setting and their surroundings. It is not a piece in which she employs a massive amount of change or movement or diversion from the original idea, but it is a piece which calls back for a second, third, fourth listen. It is in the quaintness of the sounds that the image is derived. The technique that I am able to grasp is her ability to collage very recognizable sources into an image where there is not a massive amount of motion, but a definite representation of a setting drawn in mind, where I am able to focus strongly on what is in fact “there”. It is not in Deschênes’ meticulously edited samples or seriously surreal frequency modulation, but rather in the simplicity of layers and time.

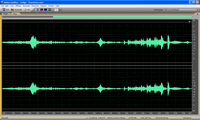

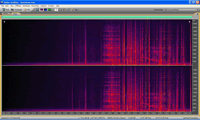

The piece that I have composed, MetaLogique, is a sort of “response” to Indigo and is based on recorded, and somewhat recognizable, sound sources. The ambience of the evening in an urban environment compiled with an axe, a metal shovel, footsteps, voice, and a mailbox. The idea was to very lightly edit the samples not beyond recognition and allow the ambience and varying textures shine through to open the listener’s imagination to gesture and movement.

Marcelle Deschênes’ Indigo is published on petits Big Bangs, available through empreintes DIGITALes. The author’s MetaLogique is available in SONUS.ca.

Bibliography

empreintes DIGITALes. Marcelle Deschênes biographical data. 2006. Trans. François Couture. http://www.electrocd.com/en/bio/deschenes_ma. Last accessed 4 April 2008.

Daunais, Paule and Hélène Plouffe. “Marcelle Deschênes.” Encyclopedia of Music in Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia Historica, 2007. Internet. Available online at http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=U1SEC891177. Last accessed 4 April 2008.

Grimm, Jacob L. and Wilhelm C. Grimm. 1812. Snow-White and Rose-Red. Available online at http://www.4literature.net/Jacob_and_Wilhelm_Grimm/Snow_White_and_Rose_Red. Last accessed 8 April 2008.

Lefebvre, Marie-Thérèse. La Création musicale des femmes au Québec. Montréal: Les Éditions du remue-ménage, 1991.

Mountain, Rosemary. “The Expansive Spirit of Marcelle Deschênes.” Musicworks 86 (summer 2003).

Perrault, Charles. Bluebeard. 1698. Available online at http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/perrault03.html. Last accessed 8 April 2008.

Social top